Photo by Shawn Hazen.

Photo by Shawn Hazen.

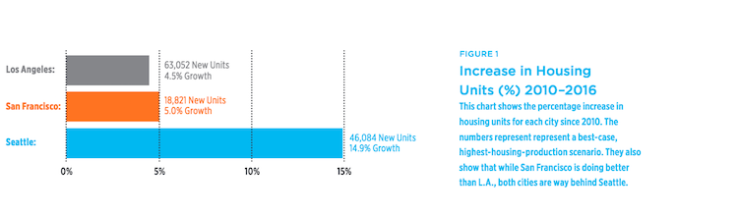

While San Francisco is becoming infamous for its lack of progress in addressing its ever-worsening housing crisis, Seattle residents joke that their official city bird should be the construction crane. The city is certainly experiencing a boom in production of mixed-use high-rise development, particularly in its dense urban center districts, where nearly 27,000 units of housing have been produced in the last ten years.[1] But there is also another, quieter, revolution going on - the sustained development of housing in low-rise areas (defined as areas with a 40-foot building height limit).[2] Housing in these areas take different forms including, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), townhouses, rowhouses and small apartment buildings with 5–9 units. Seattle is showing that it is possible to add a significant amount of housing by densifying existing neighborhoods. Between 2006 and 2016, Seattle built nearly 16,000 new units below the magical 40-foot height limit.[3] This is in comparison to San Francisco’s production of only 1,900 new units in 1 to 9-unit buildings from 2006–2015.[4] Seattle has roughly twice the land area of San Francisco (83 square miles compared to 49 square miles) and 75 percent of its total land area is zoned for single-family homes and low-rise development.[5] Similarly, San Francisco has 63 percent of its current housing stock in single-family homes and 2–9 unit buildings.[6] Given these similar land use patterns it is surprising that Seattle is producing so much more low-rise housing per square mile than San Francisco. These shorter buildings are important: not only are they less expensive to build, they tend to fit well into already developed neighborhoods.

The story of Seattle’s low-rise development boom is deeply rooted in two major changes: the implementation of the State’s Growth Management Act of 1990 (see article. page 9) and the expansion of the employment base in downtown Seattle.

Impact of the Washington State Growth Management Act of 1990 In 1990

Washington passed a Growth Management Act which mandated that population growth be concentrated in urban areas instead of accommodated through sprawl and development of rural areas. Counties were required to designate urban growth areas that would accommodate growing populations over time. Penalties for not building housing could include loss of tax revenue. King County designated Seattle (it’s largest city) as one of these urban growth areas. In response, Seattle developed a comprehensive strategy to accommodate projected population growth of 120,000 people by 2035.[7] A key component of that strategy was the urban villages concept. The urban villages strategy allowed for tall, dense development in certain areas (called urban centers, including Seattle’s Downtown) . But Seattle also created compact, lower density neighborhoods (called hub and residential urban villages). By designing these urban villages around transit hubs and adding more transit capacity, the city was able to eliminate parking requirements for homes in urban centers and those within 1/4 mile of “frequent transit service,” making it possible to add more housing in dense neighborhoods.[8]

Growth of Jobs in Downtown Seattle From 1995-2004

In the wake of the passage of the Growth Management Act, approximately 28,000 total new units of housing were built in Seattle. That number jumped to nearly 63,000 within the subsequent period 2005-2016.The job growth in Seattle, led by the growth of Amazon in downtown Seattle, directly impacted the resurgence housing production in Seattle. For a sense of scale, Amazon now employs nearly 25,000 in its downtown Seattle headquarters, 20 percent of whom walk to work.[9] While many Amazon employees do live in denser high- rise development in the South Lake Union neighborhood, the increase in units in lower scale development greatly contributed to the ability of Seattle to accommodate new and existing residents.

Chart: Abundant Housing LA. Data source: US Census, HUD SOCDS

Chart: Abundant Housing LA. Data source: US Census, HUD SOCDS

Expanding Urban Villages

In 2015, Seattle adopted a Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda, that made 65 recommendations to the mayor and city council. As part of an effort to increase the supply of housing, the Agenda called for an expansion of the urban village strategy. As a result, Seattle is currently looking to expand boundaries and add density to a number of existing villages.[10][11]

Building More In-laws

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs or “in-law units”) and Detached Accessory Dwelling Units (DADUs or “backyard cottages”) are a growing part of the housing equation as well. These units — which can be either within an existing building, a basement unit in a single-family home, or in a separate structure on the same lot — were first legalized in Seattle in 1994. An expansion of the law passed in 2009 to allow detached units on single family home lots. Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda called for further loosening restrictions to building ADUs as part of a strategy to expand access to single family home areas. In May 2016, the City Council released a report detailing the local regulatory barriers to producing these types of units with an eye towards making them more prevalent in Seattle’s housing stock. Some ideas include: ending requirements that the property owner live in the primary residence, and that off-street parking be provided for ADUs on single-family home lots. It should be noted that Seattle has yet to start building lots of in-law units. Since 1995, nearly 1500 ADUs have been created and permits for ADUs have steadily increased every year since 2007.[12]

Successful densification is not the only reason to study how Seattle was able to promote lower-scale development . A recent study from the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at University of California, Berkeley noted that smaller scale multi-family buildings are cheaper to build than both single- family homes and high-rise apartment buildings.[13] Since construction costs are the major driver of the financial feasibility of housing projects — and thus, the affordability of housing — it’s smart to look at ways to maximize this type of development.

San Francisco has already made some steps in the right direction.

San Francisco can continue to make progress on building more housing units by finding ways to maximize development within existing zoning. Seattle shows how it is possible to succeed at building more housing by doing so at a smaller scale. While cities also need to build larger, taller developments as well if they are going to effectively address their housing shortages, Seattle has shown that smaller buildings can play a key role.

Endnotes

[1] Seattle Residential Permits through Q4 2016. http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/p2604745.pdf

[2] Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections. Seattle Lowrise Multifamily Zones. https://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/dpds021571.pdf

[3] Seattle Residential Permits through Q4 2016. http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/p2604745.pdf

[4] San Francisco Planning Department. 2015 Housing Inventory Report and 2010 Housing Inventory Report. http://sf-planning.org/citywide-policy-reports-and-publications

[5] City of Seattle Land Use Zoning as of February 2013. http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/OPCD/Demographics/AboutSeattle/Citywide%20Land%20Use%20Zoning%20Details.pdf

[6] San Francisco Planning Department. 2015 Housing Inventory Report. http://default.sfplanning.org/publications_reports/2015_Housing_Inventory_Final_Web.pdf

[7] City of Seattle. Seattle 2035 Development Capacity Report – Updated September 2014. http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/p2182731.pdf

[8] Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections. Seattle Lowrise Multifamily Zones. https://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/web_informational/dpds021571.pdf

[9] https://www.amazon.com/p/feature/asmcnzrfbvt288g

[10] Seattle Times: http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/politics/draft-maps-of-some-areas-look-to-denser-future-for-seattle/

[11] City of Seattle, Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda. http://www.seattle.gov/hala/about#thegrandbargain

[12] Sightline Institute. “Returning Seattle to it’s Roots in Diverse Housing Types”. www.sightline.org

[13] Terner Center for Housing Innovation. Report “Right Type, Right Place”. March 2017. https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/right-type-right-place

[14] San Francisco Planning Department. “Affordable Housing Bonus Program Potential Soft Sites”. February 2016. http://www.sf-planning.org/ftp/files/plans-and-programs/planning-for-the-city/ahbp/SFPlanning_AHBP_PotentialSoftSites.pdf