Imagine if California could combine half the Bay Area’s 101 cities into a more manageable 50, or even 25. Imagine that, decades ago, a regional plan had generated high-density development at BART stations like MacArthur, Walnut Creek or Hayward — and that the private sector had responded by actually building shopping centers near BART stations instead of near highways. Or that major developers — of places like Transbay, Diridon, Alameda Point or the Concord Naval Weapons Station — went to Sacramento for approval rather than a local city council.

Whether this sounds like a frightening top-down dystopia or a rational approach to good regional planning, it is a scenario that roughly describes what has been happening in the Sydney metropolitan region in recent years.

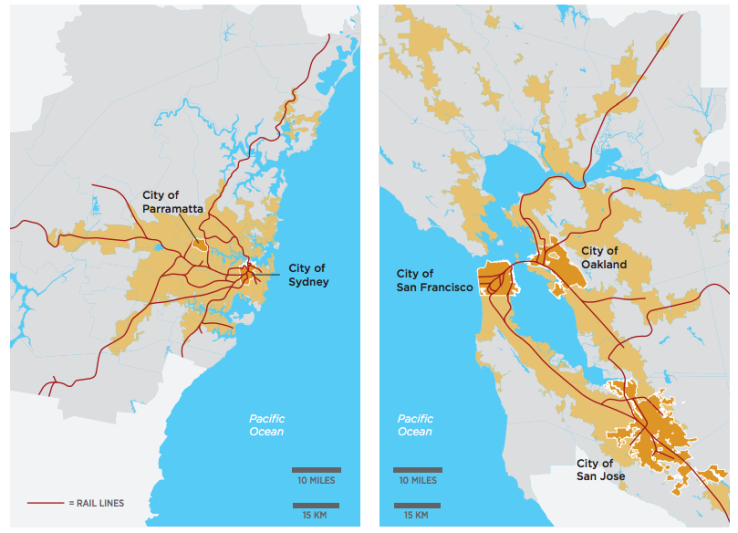

People often compare Sydney and the Bay Area, and for good reason. Both regions are built around a beautiful bay and harbor, with a high-rise downtown set against blue water and an iconic bridge. Both contain a mix of early 20th-century walkable neighborhoods surrounded by post–World War II, auto-dependent sprawl. Both regions are also desirable places to live and have extremely high housing costs. (The average home in the Sydney region is over $1 million Australian, or about $800,000 US; the median home price in the Bay Area is close to $650,000 US and over $1.1 million US in San Francisco).

Despite the region’s similarities, Sydney’s planning system is entirely different from the Bay Area’s, primarily because of the strong role of its state government in planning decisions. It is worth considering what we can learn from the planning history and policy of another region, particularly one that is as concerned about protecting its natural beauty as the Bay Area. This article briefly explores the spatial history of the Sydney metropolitan region, explains some of the key differences in its planning and policy framework for transportation and land use and draws some lessons for the Bay Area.

The State of New South Wales, not the city, is planning and delivering a major redevelopment of the Sydney waterfront. Barangaroo will have more than 3 million square feet of office space and thousands of residential units and is Australia’s first carbon neutral community. The project, seen in a rendering above, is being built by a private developer, LendLease, and the City of Sydney is essentially an influential stakeholder, articulating the importance of values like urban design.

So, is Sydney getting better results? In some ways, the answer is unequivocally yes: There is true walkable urbanism around suburban rail stations and better alignment between transportation investment and where growth occurs. However, the Bay Area is tackling issues of equity and affordability more vigorously than Sydney. In addition to our higher requirements for affordable housing (2 to 4 percent affordable was the highest we heard about in Sydney, and cities in New South Wales are not allowed to set inclusionary percentages), lower income residents in Sydney are much less likely to live near the region’s core.

While the Bay Area’s longer affordability crisis has led to more policy innovation in housing, it hasn’t led to success in solving these transportation and land use challenges. Sydney’s better transit-oriented development, particularly in the suburbs, in combination with a regional transit card, daily fare caps and seamless transit connections means residents of outlying areas can more easily access the prosperity of the region and are much more likely to take transit instead of drive (25 percent of residents in the Sydney region take transit to work compared with 10 percent in the Bay Area, and 70 percent take transit to the central business district (CBD) compared with about 55 percent to downtown San Francisco).

While this article makes comparisons between Sydney and the Bay Area and draws some lessons from Sydney, we do so with caution and humility: What seems to work better on the other side of the planet may not necessarily transfer successfully to our region.

How rail, ferries and regional plans shaped Sydney

The initial growth of Sydney’s metropolitan region was the result of a boom in resource extraction, like in the Bay Area. While California’s Gold Rush began in 1849 almost immediately upon the first gold discovery near Sutter’s Fort, the Sydney elite kept their 1813 discovery of gold a secret for decades, fearing that workers would leave their jobs to seek potential riches. But by 1850, the “secret” had spread throughout Australia, and gold fever began — along with a subsequent population and economic boom. Growth pressures led to major transportation investments to connect the region. By 1855, a rail line was built, linking Sydney to Parramatta (only 70 years after the first Sydney settlement and almost a decade before the first rail line from San Francisco to San Jose).

Overall, Sydney’s 19th- and early 20th-century planning histories are similar to the Bay Area’s. The region had a historic walkable core on its waterfront with rail hubs in a few places. It then grew outward along streetcar lines from the historic center. In fact, Sydney had one of the largest tram systems in the world, with 1,600 cars in service. (Ridership peaked in 1945 with about 400 million trips per year and the system closed in 1961, a hundred years after it began. Comparatively, peak ridership on San Francisco’s Muni system in 1946 was 326 million.) In addition to rail and streetcars, the region also developed around its extensive ferry network. Unlike the San Francisco Bay, the Sydney Harbor and river is quite narrow, making ferry transportation more viable. Its width ranges from less than half a mile to about 2.5 miles (compared with 3.5 to 11 miles for our bay).

Sydney even had a “Greater Sydney Movement” in the early 20th century, inspired by the amalgamation of New York’s five boroughs, to combine councils and manage planning more effectively on a regional scale. But the idea never moved forward due to local opposition. Similarly, the “Greater San Francisco” movement starting in 1907 was met with derision by Oakland leaders, who thought their city should be the Pacific Coast’s future hub, not the windy, foggy earthquake- and fire-ravaged peninsula, which was not even on the transcontinental railroad route.

As in the Bay Area, Sydney saw significant growth in the post–World War II years as the region took in hundreds of thousands of immigrants, mostly from war-torn Europe. While new migrants initially settled in communities that were built around the rail system, auto-oriented growth in the postwar years filled in the places between rail stations, leading to undifferentiated sprawl that would be familiar to Americans. Still, Sydney came late to freeway investments, so most of the prewar neighborhoods near the city center are largely intact and the region’s suburban growth pattern is less freeway-oriented.

The state may at times, allow the city to maintain the planning control. This is happening at Sydney’s Green Square neighborhood, where the state may allow the city to maintain planning control over a major development project but may use the state development arm do the infrastructure and building. Rendering courtesy City of Sydney Council.

During the post–World War II fast-growth period, Sydney did pursue regional planning (just as the Bay Area created BART, the Air District, BCDC, and the Bay Area’s first regional plan in the 1960s). In 1948 the Sydney region produced a plan that called for a greenbelt stretching from Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in the north in an arc around to the south, and allowed for the building of satellite cities along rail lines outside the greenbelt once the area within the greenbelt filled up. The Cumberland Plan of 1948, inspired by The Greater London Plan of 1944 developed by Sir Leslie Patrick Abercrombie, did not succeed in securing the greenbelt, in part because it radically underpredicted the rate of the region’s growth. The plan was built around the assumption that the region would grow from 1.75 million residents in 1947 to 2.25 million by 1981. Instead, the region added 500,000 people by 1961, with many of those residents moving into the Western suburbs (including areas that had been proposed for the never-realized greenbelt). The Cumberland plan was never formally adopted and its ideas were not followed — both because it did not influence the state government and because it was also rejected by local councils.

In 1968, the Sydney Region Outline Plan tried to manage growth by concentrating it along existing rail corridors that extended out from the CBD with open space in between (inspired by the “finger” plan for Copenhagen). Recognizing the fast growth from 1945 through the 1960s, this updated plan assumed the region would grow to 5 million by 2000 (though it instead grew to 4 million by 2001). One highly successful policy in the plan was to encourage major regional shopping malls to locate near rail stations in centers identified in the plan. Due to the assurance of ongoing infrastructure investment and strict planning controls, the private sector did focus its major retail development in these transit-oriented places, as opposed to the more auto-oriented shopping malls in the United States. Now, these same concentrated retail centers are evolving into larger mixed-use employment and entertainment centers.

Understanding the main differences between planning in Sydney and the Bay Area today

There are three key ways that regional planning in Sydney is more powerful than in the Bay Area. The state can carry out local planning; authorities can combine transit investment and station area development to shape the region; and it is possible to change the geographic boundaries of city governments.

1. The state government, through its Minister of Planning, retains power over local government and can control major development projects.

Like in the United States, the Australian federal government has a small role in urban planning issues, mostly limited to administering environmental laws. However, the new federal government has created a Minister for Cities, hoping for more investment in urban infrastructure. Though it is still too early to assess what will happen, state governments in Australia maintain power over local planning and development (particularly the Minister of Planning in New South Wales), whereas in the U.S., states have generally delegated their planning powers to cities. The Minister of Planning can declare virtually any development to be “state significant” or in the “state interest” and make all planning approvals for it. This power goes back to the 1979 Environmental Planning and Assessment Act, which defined the powers of the State Department of Planning and Environment; set up the Planning Assessment Commission to make decisions on major applications; and established Joint Regional Planning Panels to make some development decisions. Local governments can make local environmental plans, but they have to conform to state and regional plans. In contrast, California’s landmark environmental planning law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA, passed in 1970), tends to hand power to litigants, not to state bureaucrats. California’s 2008 regional planning law, SB 375, requires regions to create plans, but still does not require city plans to conform to regional plans; it is non-binding on cities. Sydney does have some overt power in the planning equation. Its “Sustainable Sydney 2030” plan identifies growth areas and the scale of development contemplated. The city can also engage the public to support its visions and can push them through the planning and political process.

But the state retains the authority to identify major development projects and remove them from local control. Some of the Planning Minister’s direct power also comes from appointments to key decision-making entities, such as:

- Planning Assessment Commission (determines major development applications such as coal mines, major industrial development and development in some special areas)

- Joint Regional Planning Panels (determine development applications for all development of more than $20 million in value)

- Central Sydney Planning Committee (determines major applications in the city of Sydney)

Finally, while the state will likely retain authority in planning into the future, it is also establishing a new powerful regional commission to carry out its work (which is further explained below).

2. The state and region are able to shape a transit-oriented, polycentric metropolis — a “City of Cities” — by locating major transportation investment around key rail nodes.

The Sydney region can be divided into roughly six major areas, each with its own regional center (these include Sydney CBD/North Sydney, Parramatta, Penrith, Campbelltown and Liverpool). Major office, cultural and retail facilities are planned for each “strategic centre” and are linked via rail. Supporting this polycentric form enables Sydney to grow in a way that provides residents more equal access to jobs, recreational opportunities, housing and cultural amenities. This form is particularly important for equity considerations given that the bulk of the population is increasingly located in the more affordable Western suburbs, while the region’s knowledge economy remains concentrated in the east, near the water.

While regional plans in California may call for reinforcing specific sub-centers (such as downtown Oakland and downtown San Jose), there are few planning tools to make such a vision a reality. Quite simply, in Sydney there is more willingness to identify and accept the notion of prioritizing key centers, and there are more tools to shift growth — though these tools mostly flow from the state government.

The case of Parramatta illustrates the state’s role. Fifteen miles upriver from Sydney’s center, Parramatta was initially settled for farming shortly after the first European colony in 1788, when the British realized the area around today’s downtown was not fertile. Parramatta has remained the key center of Western Sydney for the subsequent centuries and is today dubbed the region’s “second CBD.”

There are five key elements of the state’s role in Parramatta:

- The state has a vision to grow the city’s job base to over 100,000 and has been shifting thousands of state government jobs there for several decades (including 4,500 jobs in the 1980s and thousands more in recent years, including the headquarters of the Sydney Water enterprise and the State Police).

- The state is investing in the existing heavy rail network to improve speeds, particularly between Parramatta and the Sydney CBD (similar to what London did with new investment in rail linking The City with Canary Wharf).

- The state is building a new light rail system with Parramatta at the center of the rail network, including new connections to the Sydney Olympic Park, a major redevelopment area.

- The state is establishing a “Greater Parramatta” that will combine the existing city with surrounding councils to make a new city of nearly 500,000 residents.

- The state is allowing for additional development capacity in both the downtown and other areas of Parramatta (particularly for health services and education). For example, the Parramatta CBD will have an increase in floor area ratio (FAR) from 10:1 to 15:1.

Despite the goal to decentralize Sydney and promote job centers in the western suburbs, there is still an interest in maintaining and strengthening the historic downtown in Sydney. With about 350,000 jobs (comparable to downtown San Francisco) the Sydney CBD is the undisputed regional center and it alone accounts for 20 percent of the state’s economy and 6 percent of the country’s gross product. To reinforce its importance, the state government is funding a second rail crossing across the harbor, as well as a light rail through the core of the downtown.

Sydney is also embarking on a major experiment in regional planning through the creation of the Greater Sydney Commission (which brings back some of the unrealized vision of the Greater Sydney Movement). Still in its infancy, the Commission has the powers of the State Minister, but may be able to work across traditional government silos (jobs, transportation, housing, environment, etc.) to produce both subregional and regional plans to guide growth. The commissioners are appointed by the Planning Minister and have many of the state’s direct powers within their jurisdiction. The Commission is nonetheless considered a quasi-independent body that is responsible for the development and implementation of regional plans. Local councils will also have to develop their own environmental and land use plans that are in alignment with the regional plans. This power is more akin to what exists in the Portland region, whereas regional plans in California are merely advisory.

3. The state government is consolidating local governments, reducing the number of councils from more than 40 to about 25 in the Sydney region.

These more than 40 councils in the Sydney region are the primary local governments and are responsible for preparing local environmental plans for their areas. These plans control development through zoning and other controls. Councils review development applications and have representatives on state and regional bodies, such as the Joint Regional Planning Panels and the Greater Sydney Commission.

Like in California, local councils are creatures of the state and exist at the pleasure of the state government. Unlike California, the state of New South Wales has retained the legislative and political power to propose consolidation of cities. The current proposal to reduce the number of councils from about 43 to 25 can move forward without the concurrence of the cities. There is undoubtedly some opposition to the concept, and some councils are challenging the proposal in court. There are also critiques of how the consolidation will be implemented. For example, the proposal is for the local government council of Parramatta to be split in half. Its entire southern portion will be spun off to a new city while its northern part will be combined with five other local government areas. The southern part is lower income and more likely to vote politically to the left, while the northern part is more likely to vote conservative. The politicization of the city boundaries has also historically been an issue in Sydney, where the state has adjusted city boundaries from time to time depending on political voting patterns. Rezoning for political reasons certainly undermines the good government benefits of having fewer local governments.

(Several elected mayors and general managers the SPUR group met with this past April expressed support for the concept of consolidation, resigned to the fact that they would likely lose their jobs once their council is combined with parts of several others and the town develops a new name and eventually a changed identity.)

Maps by John Beutler, SOM

Beyond the “Goat Cheese Curtain”

Imagine if the Bay Area was a band of urban development that stretched from San Francisco 40 miles east to Antioch and from San Rafael 20 miles south to Daly City. This is roughly the shape of the main urban footprint of the Sydney region. To get a sense of the job concentration on one side of the region, imagine if downtown San Francisco were located by the Golden Gate Bridge, and Ft. Baker (on the Sausalito side of the bridge) was the region’s second major job center. In Sydney, half the region’s population is in the Western Suburbs, west of Parramatta, the last town where the ferries go. This results in two dramatically different regions. One is wealthy, hilly and built around water (eastern Sydney) and the other is a flat, more auto-oriented and sprawling, far from the harbor. There are significant economic and public health differences, which will be exacerbated by climate change. Sydney’s Western Suburbs are lower income and typically 10 degrees hotter than the breezy east near the water. The western suburbs are also further from the specialized knowledge jobs that are concentrated in and around the Sydney CBD. With relatively slow rail, this spatial structure creates a transportation problem, as people need to cross the entire metropolitan area to reach many jobs. Some refer to a “Goat Cheese Curtain” across the Sydney region, where wealthier households east of the curtain are likely to have goat cheese in their fridge (and more money in their bank accounts). This cultural reference has no backing in data and is unlikely to have a corollary in the Bay Area, given that the relative likelihood of goat cheese in one’s fridge is roughly similar across our entire metropolitan area.

Conclusion: Lessons for the Bay Area

Drawing lessons from cities and regions under vastly different legal systems and cultural contexts is always difficult. But there are a few ideas to draw from the planning context of Sydney that apply to the Bay Area.

1. There should be an override to local government veto power over land use to express the regional or state interest. In other words, someone other than the local city council or local government should have final say on some land use decisions, particularly major plans or development in the state or regional interest. We’ve already done this in California by exempting the University of California and California State University from local planning. We could consider expanding this exemption to key transit station areas or developments of a certain scale. Once you accept that there should be some kind of an override to local decisions, the question is who has that override (a state agency or a regional government, for example)? And perhaps most importantly, how do you define the “state interest”? This designation should not become an easy excuse to avoid all local planning policies or good urban design principles simply to further “state significant” economic growth. This issue is currently a big point of discussion in Sydney over the state’s controversial decision to build a major casino on a waterfront site previously designated as parkland.

2. City boundaries should not be assumed to be sacrosanct for eternity. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, city boundaries in the Bay Area were constantly in flux. In the post–World War II years, many Bay Area cities expanded to capture land and its corresponding tax revenue. In the decades since Prop. 13 (where many local governments suffered fiscal crises), we have yet to revisit those boundaries to see if they still work for us. Some cities are simply too small to effectively deliver services or to effectively make land use planning decisions at the right scale. We should reconsider some of our local government boundaries, if for no other reason than to better deliver services and capture revenue at a more efficient scale.

3. Effective transit-oriented development means putting destinations — like retail or jobs — around rail stations so that people have a reason to take transit. Too few of the Bay Area’s rail stations have major activity around them. Sydney has done a much better job than the Bay Area in shaping its growth around rail. In addition to locating big shopping complexes near rail, 35 to 40 percent of Sydney’s jobs are located around rail compared with less than 25 percent in the Bay Area. This positions Sydney as better able to continue to make rail investments that will get lots of riders. Bay Area regional agencies, transit operators and local governments could revamp TOD policies to focus on buildings and land uses that will get more riders (i.e., jobs, shopping, education facilities, not just housing) and will have the biggest impact on shaping the region’s growth around transit.

We are at a time of great opportunity and inflection in regional planning in the Bay Area. We are in the middle of our first update to Plan Bay Area, our region’s land use and transportation plan. While the plan cannot compel local jurisdictions to support development in the regional interest and relies on insufficient funding incentives, it is a framework for growth that is now state law and must be updated every four years. Also, as a move toward articulating the state interest in local planning, Governor Brown recently proposed making housing “as-ofright” if it complies with local zoning and meets certain affordability requirements. At the same time, two of our regional government agencies (ABAG and MTC) are in the midst of merging. Having one regional agency that combines transportation, land use and the convening of local governments should help the Bay Area more effectively achieve some of the good land use outcomes visible in Sydney. Having a comprehensive regional planning agency should also help us better prepare for emerging regional issues like sea level rise, economic dislocation and the rise of autonomous vehicles. So while we may today look with envy at regional planning tools in other regions, we should also be excited about the possibilities for better planning in the Bay Area in the coming years.

Photo by Rob Steinberg

Comparing Sydney and the Bay Area

The Sydney region is Australia’s largest, with nearly 5 million people. The City of Sydney, the region’s central city (photo above), is quite small, however, with only 160,000 residents, yet 370,000 jobs. Most of the region’s population lives in other communities, but none have the name recognition of Sydney. So the metro area is just called Sydney. In comparison, the Bay Area is much smaller on a national scale and is a polycentric region where San Jose is the largest city with over 1 million residents and the second largest city is San Francisco with 867,000 residents. Still, both regions are projected to continue to grow quickly over the coming decades.

Sydney

Population: 4.9 million (2016). Projected to grow to 7.08 million in 2041.

Jobs: 2.4 million (2016). Projected to grow to 3.4 million in 2041.

Economic output: $325 billion (AUS) (21.4 percent of the nation’s economy and 69 percent of the state’s)

Bay Area

Population: 7.6 million (2015). Projected to grow to 9.6 million in 2040.

Jobs: 4.0 million (2015). Projected to grow to 4.7 million in 2040.

Economic output (2014): $668 billion (USD) (3.8 percent of nation’s economy and 29 percent of the state’s)