WHAT HAPPENED

Both San Francisco and Oakland passed legislation making it legal to grow and sell produce within city limits. Selling homegrown fruits and vegetables was previously illegal in both cities.

WHAT IT MEANS

The passage of the legislation puts the Bay Area at the leading edge of policy on this issue, providing a model for other cities across the country. But it raises an underlying question for policy: Should the goal be significant food production for the local population? Or should a city instead promote urban agriculture as a way to educate city residents and better connect them with local food systems? To explore these questions, SPUR launched a Food Systems and Urban Agriculture program this year.

On April 20, Mayor Ed Lee, Supervisor David Chiu and Supervisor Eric Mar led what may have been the first “salad toast” at Little City Gardens in the Excelsior District. Raising bowls of San Franciscogrown mixed greens, they were joined by dozens of urban agriculture supporters celebrating the mayor’s signing of urban agriculture zoning legislation. The bill explicitly welcomes gardens and small urban farms throughout the city and, more importantly, allows gardeners to grow food for sale in any zoning district. This change, coming on the heels of legislative reforms in cities such as Kansas City and Seattle, placed San Francisco at the leading edge of urban agricultural reform. Later in the year, San Francisco’s policy was cited as a model by urban ag advocates and planners in Oakland, Chicago and British Columbia.

Oakland soon followed San Francisco’s lead by updating its land-use and health codes. In October, the Oakland City Council changed the definition of home occupations to allow residents to grow food for sale in their yards with minimal fees. The city is still working on updating its regulations for urban agriculture on non-residential lots and for animal husbandry in the city. Advocates in Berkeley have also begun pushing for urban agriculture code changes, but the city has yet to pass any legislation.

While policymakers in San Francisco and Oakland deserve credit for shepherding these changes, in both cases the driving energy came from grassroots efforts. The legislative ball got rolling in San Francisco when Brooke Budner and Caitlyn Galloway, the farmers/proprietors of Little City Gardens, decided that rather than get a conditional-use permit for their operation they would get the law changed. In Oakland, forces mobilized after the city cited urban farmer and author Novella Carpenter of Ghost Town Farm for growing food on a vacant lot without first obtaining a conditional-use permit, which costs $2,800. In both instances, community groups rallied around the issue and helped advocate for change. Decades earlier, cities had pushed farming away; now energized urban farmers spearheaded efforts to bring it back.

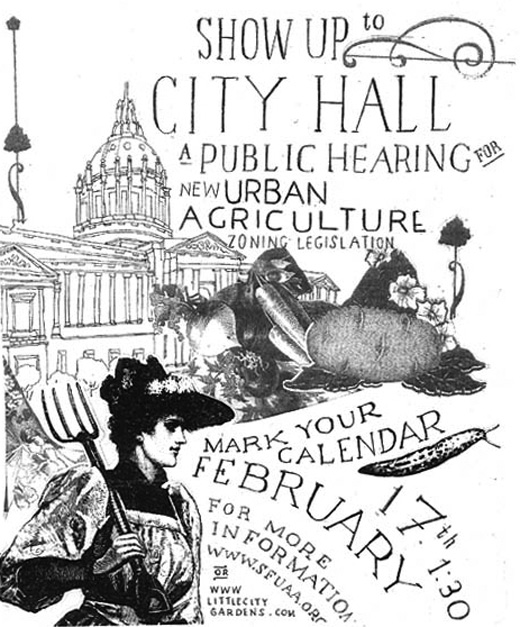

Overflow crowds attended the San Francisco Planning Commission hearing in February, which city planning staff described as an unprecedented “love fest,” with commissioners competing to demonstrate the depth of their farm cred before unanimously approving the proposed changes. In Oakland, the Planning Department held a weeknight community meeting to discuss changes. Nearly 300 people showed up. How to regulate animal husbandry was the hot topic of the evening. (At press time, Oakland was still developing its proposal.)

From left, the proprietors of Little City Gardens and the fruits (and vegetables) of their labor; Mayor Ed Lee signing new legilsation in April.

The zoning change in San Francisco has influenced similar changes in other cities, but its impact within San Francisco is still unknown. The number of urban farms on private land remains quite small, and few gardeners have applied for a permit under the new law. Though the legal obstacles may have been navigated, many other ones still stand in the way. That two high-profile farms — Hayes Valley Farm and Little City Gardens — both faced land tenure issues in 2011 points to the challenges ahead.

The picture on public land is a bit more mixed. In October the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission took a step toward further supporting urban farms and gardens by offering to waive fees for a limited number of new water hookups and commissioning a feasibility study for urban agriculture projects on two of its properties. But other public agencies have not been as active in promoting new community gardens or farms on public land, despite the persistence of long waiting lists for existing plots.

Land access, land tenure and commercial viability remain issues for city farmers. Looking ahead, cities will need to determine how to focus their efforts. Urban farming began to take root this past year, but it will take more work by both advocates and policymakers to ensure that urban agriculture flourishes in the future.