The current economic crisis has proven to be more than a challenge to our wallets: it has tested our faith in personal agency and our optimism in the future. But this malaise has met its match in the Bay Area, where a spirit of fierce independence has always thrived. Here the bad economy has a silver lining: it has reinvigorated and mobilized the community of do-it-yourself urbanists.

A mere snapshot of this burgeoning movement, this exhibit — on view at the Urban Center from September 7–October 29 — includes a selection of these projects, organized into four categories. DIY markets provide new, collaborative business models and environments; the better streets movement is working to invigorate and breathe new life into the city's public realm; new urban gardens bring the restorative power of nature back into the domain of the manmade; and a new commitment to public art sees it not just as aesthetic backdrop but as a way to interpret the urban/human interface.

Together these projects reveal the ways in which small or finite efforts can blossom into larger-scale, ongoing transformations. One replanted street median might become a swath of green across a neighborhood; one online instigator might catalyze a network of social revolutionaries; one eccentric performance-art gesture might ignite a rash of annual imitators and inspire new ways of activating public space.

They also signify a porous — and more productive — relationship between grassroots activists and local government. Citizens and City officials can work together, and toward common goals. This is the domain of possibility, collaboration and creativity that others are exploring to improve the city. We invite you to do it yourself.

DIY: Streets

Outdoor Living Rooms

The second generation of furniture recreates the front stoops and sidewalk benches where historically community residents gathered. Photos by Steve Rasmussen Cancian.

Outdoor Living Rooms are vignettes of furniture installed in public spaces —simple wood fixtures that give physical form to the social life of the street: waiting for a bus, meeting outside a shop, chatting or playing a game or just lounging. Steve Rasmussen Cancian works with residents in low-income neighborhoods, in West Oakland and parts of Los Angeles, where officially sanctioned and funded improvements are hard to come by. The West Oakland Greening Project created the first outdoor living rooms with found furniture: discarded sofas repurposed as sidewalk seating. Their later iterations have been custom made out of simple materials to recreate the park benches, front stoops, and outdoor tables where a neighborhood's inhabitants have traditionally interacted with one another and created a community. At first the outdoor living rooms in West Oakland were regularly hauled away by officials, but more recently the city has informally accepted the installations and offered permits if activists would purchase liability insurance. In Los Angeles, local activists won full permitting for living rooms without fees or requirements to buy insurance, eventually drawing Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa to come build a bench.

Outdoor Living Rooms share certain features with other projects in this exhibition, such as PARK(ing) Day and Pavement to Parks. But the project is more than an effort to modify street space for human use. The living rooms enable low-income renters to lay claim to their neighborhood landscape and make their diversity and culture visible to all visitors—critical benefits when outsiders often see these neighborhoods as derelict.

Furniture designed and built by West Oakland Greening Project: Ernest "Duke" Lawson, Harlan Smith, Jody Waters, Larry Davis, and Steve Rasmussen Cancian.

Clockwise from left: Early living room using "found" sofa; furniture configuration in Los Angeles; street corner living room in West Oakland; one current iteration of furniture mimics the traditional front stoops where residents gather; team member Duke Lawson completes an installation; project coordinator Jody Waters, right, installs a planter, the "spinner box," in West Oakland. Photos by Steve Rasmussen Cancian.

Sunday Streets

Bicyclists on Third Street in 2010, photo by Colleen McHugh; pedestrians on Valencia Street in 2010, photo by Bhautik Joshi.

Originating in Bogotá, Colombia, Sunday Streets has spread throughout the world, with city governments from Kiev to Tokyo closing off main thoroughfares for the leisure of pedestrians and cyclists. In its San Francisco incarnation, Sunday Streets grants non-drivers the rare opportunity to cruise or simply meander down streets such as Valencia, Third Street, and the Great Highway without glancing over their shoulders for oncoming traffic. Performances, workshops and children's activities foster a lively atmosphere in these newly created public spaces. A volunteer-driven event that promotes exercise, sustainable transportation and economic activity, Sunday Streets has evolved into a highly anticipated and welcome urban initiative.

Pavement to Parks

Castro Commons and the Divisadero Parklet. Photos by Colleen McHugh.

Pavement to Parks is a program to temporarily reclaim "excess" roadway—under-used segments of space at intersections and along the peripheries of wide streets—and repurpose it for pedestrian use, creating small parks or plazas in areas formerly allotted to cars. The first project in 2009 redesigned the tricky interchange at Castro, Market and 17th Street and created a designated place for people within the frenzied domain of bus, car and streetcar. This temporary design then became permanent, and that ambition is shared for subsequent projects, including the first "Parklet" installed on Divisadero Street, and the modular "Walklet" at 22nd and Bartlett. Both of these latter designs were inspired by the numerous PARK(ing) Day experiments manipulating the square footage of a single parking space. The Pavement to Parks projects are permitted by the City, but paid for privately and shepherded by local merchants or community organizations who agree to oversee maintenance.

PARK(ing) Day

Left: First PARK(ing) Day in Seoul, South Korea, in 2009. Photo by flickr user america.gov. Right: A curbside library created for PARK(ing) Day 2007 in San Francisco. Photo: Lawrence Cuevas.

PARK(ing) Day originated in 2005 as just PARK(ing), a one-time experiment in how to turn a parking space—for the transacted two hours—into a park. In 2007 the PARKcycle was born: a park on wheels, sized to fit perfectly into any standard parking space. From 2008 forward, enthusiasts all over the world have joined San Franciscans into staging these small revolutions: one day, one space, one temporary transformation. But in 2009 the idea metastasized, inspiring the City's long-term experiment, the Pavement to Parks program, in de-prioritizing cars in its approach to both new and remodeled public spaces.

Left: The first PARK(ing) experiment in 2005, before and during, photos courtesy Rebar. Right: PARK(ing) Day around the world, including 2009 installation at SPUR (center), photo by Colleen McHugh; and rendering of Parklet platform prototype by rg architecture for PARK(ing) Day 2009, rendering by Riyad Ghannam. All other images courtesy Rebar, via Flickr's World PARK(ing) Day pool.

Bicycle rack prototype

Bicycle rack courtesy David Baker + Partners. Bicycle courtesy Rob Forbes of PUBLIC Bikes.

This bicycle rack is a prototype of the one designed for the h2hotel in Healdsburg, which installed a row of racks to house its collection of Public-brand bikes. The bike-share fleet is part of the hotel's commitment to sustainability, in both its design and its amenities. The architects' design process included a review of bicycle parking and bicycle rack designs around the world. Communities everywhere are making a greater commitment to accommodate and encourage bicycling as an energy alternative and as the ultimate means of low-cost personal mobility. In San Francisco, the SF Bicycle Coalition works tirelessly to implement a city-wide bicycle network, with more dedicated bike lanes and bike corrals. But the U.S. still has a ways to go to catch up to innovators in Europe. Nowhere is this more evident than in Amsterdam, which features an awe-inspiring parking garage for bicycles next to the main train station.

DIY: Gardens

Growing Home Community Garden

Photo by Colleen McHugh.

Some farms aim to do more than just grow food. Through its mission to provide a space for both housed and homeless San Franciscans to work side by side, Growing Home Community Garden brings questions of prejudice, unemployment, malnutrition and education into play. Built on a small vacant lot in Hayes Valley, the garden is more than a source of food production; it is a vehicle for building community among local residents who might not otherwise have the opportunity to cross paths. The garden's Seeding Resilience program provides access to mental health services, with opportunities for participants to simultaneously learn new skills related to cooking and nutrition, gardening, general health and strategies for stress reduction. Growing Home Community Garden is a model for projects that aim to fully integrate all members of a community, creating an environment for locals from all walks of life to interact, learn, and teach, all while working together to maintain a beautiful public space.

Lansing Street Pollinator Garden

Photo courtesy Rebar.

Once slated for development as a luxury condo tower before that project fell through last year, the vacant lot at 45 Lansing Street marred Rincon Hill as a stark symbol of hard economic times. But a citywide trend towards rehabilitation of such spaces has given rise to a new kind of development on this urban eyesore. The Pollinator Garden—a joint effort by Rebar and the Pollinator Partnership—will occupy this space, attracting butterflies, hummingbirds and other pollinator species to a garden planted with native California wildflowers. The project will transform a once-barren plot of land into a living, breathing habitat for plants, animals and the general public. Cooperating with the owners of the site (who would rather please their neighbors with a cultivated public space than antagonize them with barbed wire and chain-link fencing), the project demonstrates the potential for collaboration in transforming casualties of the recession into successful interim-use open spaces.

Greenaid Seedbombs

Vending machine and images courtesy Daniel Phillips and Kim Karlsrud, Commonstudío.

Made from a mixture of clay, compost and seeds, seedbombs are a low-tech, low-profile, borderline-subversive strategy for transforming the many dead spaces we encounter everyday in the city, from sidewalk cracks to vacant lots to parking medians. The bombs can be thrown anonymously into these derelict urban sites to temporarily reclaim and transform them into living places worth looking at and caring for. The Greenaid dispenser simplifies these guerilla gardening efforts by appropriating the accessible and familiar quarter-operated gumball machine. The bombs in each machine are a mixture of seeds unique and appropriate to the native ecology of the machine's location. Once dispensed and dispersed, the bombs can lay dormant for up to a year, but with a little water and sun, they will sprout in a few days. CommonStudío provides a series of interactive maps (accessible online or on a forthcoming iPhone app) that allows participants to geotag, photograph and share their seedbomb sites with a larger community.

Civic Center Victory Garden

Photos by Katie Standke.

Both a practical initiative to generate food and a symbolic gesture for urban agriculture, the Victory Garden grew out of the conjoined efforts of multiple organizations dedicated to urban farming in the Bay Area. Planted with a variety of organic vegetables suited to the local climate, the garden produced up to 100 pounds of produce every week—all donated to the San Francisco Food Bank in an effort to provide healthy food for those with limited access to it. Physically the garden was configured with room for social interaction, to nurture its human occupants as well as plant life. Though intended as a temporary project, the Victory Garden's support from the City, various non-profits and hundreds of volunteers served to unify the local urban agriculture movement, establish a strong precedent for future Bay Area farming projects, and demonstrate the potential for success to urban areas nationwide.

PlantSF

Before and after: Harrison St. (top) and Jerrold St. (bottom). Photos by Colleen McHugh, Jane Martin.

PlantSF, which stands for Permeable Landscape as Neighborhood Treasure in San Francisco, is a program to convert portions of sidewalks into planted areas, restablishing a direct connection to the soil beneath the concrete. These plantings reduce the volume of stormwater in the city's already overloaded sewer system, while simultaneously beautifying the street—adding a bit of green into the manmade landscape to create a more hospitable environment for pedestrians and residents. The program was founded in 2004 by Jane Martin after she took a jackhammer to the sidewalk outside her own home in the Mission, and decided to help others do the same. PlantSF supports and educates individual property owners as they navigate the city's permit process and create a plan for the redesign of the sidewalk or street space they've targeted. So far more than 400 projects have been undertaken in neighborhoods all over the city, using native and drought resistant species to transform small portions of public space into thriving, and sustainable, green spaces.

Hayes Valley Farm

Photos by Zoey Kroll.

The establishment of the Hayes Valley Farm earlier this year saw an abandoned freeway on-ramp transformed into a thriving example of urban agriculture. Closed off to traffic after the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, the defunct ramp spent the next 21 years as an unused, blighted structure in the neighborhood. When the City declared the site open for temporary green use earlier this year, community members turned out in droves to get the project underway. Currently in its first phase of using fava beans to develop nitrogen-rich soil for future plantings, the farm is planned according to permaculture design methods, which replicate the biological relationships found in natural ecosystems. Hayes Valley Farm also hosts a range of programs for the general public, building a sense of community around the farm by using it as a platform for educational, social and recreational activities.

Woolly School Gardens

A Woolly School Garden installed at the Frida Kahlo High School in Los Angeles. Photo by Alex De Cordoba.

The Woolly School Garden program gives K-12 schools an easy and affordable way to create their own garden classroom. With a set of Woolly Pockets—made by the L.A.-based company of the same name—and a kit that includes soil, seeds, instructions and a curriculum, any school can bring students out into the sunshine to learn about plants, gardening, and nutrition.

Woolly Pockets are soft-sided garden containers made from felt and recycled plastic bottles. They can be configured in any format, and are ideal for small, awkward or otherwise unaccommodating spaces. The "Wally," for example, is a vertical pocket, and works especially well on walls and fences or even mounted on a free-standing structure. Modular, light and flexible, the pockets allow you to create a garden anywhere: parking lots, rooftops, any available wall, and even indoors. As Woolly Pockets inventor and company founder Miguel Nelson says, schools "don't have to tear down any buildings or cut up any concrete. They don't need a tractor, they don't even need a shovel!" The company even helps schools raise the funds for a garden kit (a thousand dollars) by connecting them to a donation network it maintains on-line.

Greening Guerrero

2010 median photo by Colleen McHugh; neighborhood plan rendering by Project for Public Spaces.

The Greening Guerrero project's straightforward aim to replace the concrete medians along the San Jose/Guerrero corridor with plants and trees has struck a chord with community members, who have provided a majority of the funding and support for this neighborhood beautification and traffic calming initiative. One of the many neighborhood improvement projects of the San Jose/Guerrero Coalition to Save Our Streets, Greening Guerrero is just one step in the coalition's broader goal to improve quality of life and the overall pedestrian experience in the area. With support from the City, the coalition has devised its own neighborhood plan and implemented a slew of changes to reduce traffic speeds along the San Jose/Guerrero corridor. Where cars once sped by at 65 miles per hour and frequently crashed into surrounding houses, two traffic lanes have been removed, bicycle lanes painted, the median widened and planted. The Greening Guerrero project also aids in calming traffic: drivers reduce speeds when streets are planted with trees and vegetation because it indicates that they are in a neighborhood and not on a freeway. As a ground-up effort by community members to take an active role in the improvement of their own neighborhood, Greening Guerrero has set the example for similar grassroots initiatives in communities around the city.

DIY: Markets

5M Project

TechShop photo by TechShop staff photographer; Hub interior photo by Eugene Chan.

The 5M Project is an experiment to redevelop the San Francisco Chronicle site and its surrounding four acres, transforming the area into a new kind of creative innovation center. Current tenants, all of which were chosen for their interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches, include the Hub, which supports social entrepreneurs with a la carte office services; TechShop, which offers non-professionals access to high-tech fabrication tools and workspaces; and Intersection for the Arts, a nonprofit artists collective. These amenities provide the infrastructure and networks, in one location, that aim to enable a more diverse set of ideas and initiatives than traditional offices or corporate campuses can. But the campus is more than one-stop shopping for the do-it-yourselfer. The project's real innovation is its ambitious scale of placemaking: physical spaces that encourage serendipitous but substantive interaction, that support the collective agendas that emerge from that interaction, and that allow for continual experimentation with user-driven business models. The pop-up shops, labs, studios, stages and event spaces imagined for the future campus are places designed to create and sustain a collaborative community, instead of a miscellany of businesses that merely co-exist.

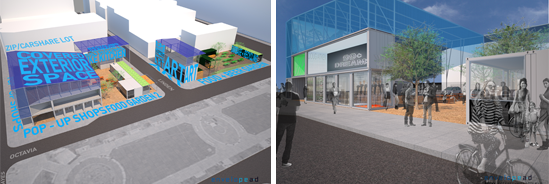

Proxy

Renderings courtesy envelope A+D.

Proxy is a scheme to reanimate a dead space—a pair of lots left vacant by the demise of the Central Freeway in Hayes Valley—with a temporary but ambitious complex of commercial and community functions. The project combines gallery and event spaces with food stalls and pop-up shops, along with a garden and a car-share lot. With structures that are open, transparent, highly flexible and recyclable, the program allows for a continual turnover of tenants and visitors, as vendors, consumers and other users experiment with exploiting its amenities for their own endeavors. Proxy's name comes from this deliberately short-term experiment: during its lifespan of two to five years—the down time before permanent development resumes—the neighborhood residents and the site's developers will discover together what works best.

San Francisco Underground Market

Photo of June 2010 market by Robin Jolin.

Many home bakers and gardeners aspire to be sellers as well as producers, to earn some money from their hobbies or even launch a career as a professional. But the traditional farmers' market requires that prepared food sold there is made in a commercial kitchen, shutting out the amateurs no matter the quality of their wares. For Iso Rabins, founder of forageSF, which promotes the harvest and consumption of local, wild plants, this challenge was overcome with the creation of a private market venue, where unlicensed producers can sell to shoppers who become "members" to get in the door. The Underground Market is intended as an incubator, helping new sellers raise money and visibility and eventually become "legitimate." The first market was held in December and by its fourth outing was attracting 70 vendors and more than 2,000 visitors.

Carrotmob

Carrotmob's first event in 2009, at the K&D Market in the Mission. Photo courtesy Carrotmob.

Carrotmob is a new kind of social activism, a "flash mob" of consumers, organized through social media tools to collectively pool their buying power, on a pre-determined day at a pre-determined vendor. Vendors "bid" for the patronage of the Carrotmob by promising a portion of the day's profits towards the implementation of an environmentally positive improvement in their business. Carrotmob shoppers buy what they would be buying anyway that day, and the vendor ends the day richer and greener. This exploitation of capitalism—the "carrot"—is a simple concept, intended to translate the small-scale repercussions of one shopper and one transaction into lasting global change.

Mobile food carts

Photo by flickr user flickrwater.

Mobile food carts can be found throughout the Bay Area, but their presence has been especially strong in the Mission, where culinary entrepreneurs enjoy a highly supportive and receptive clientele. From the ubiquitous bacon-wrapped hot dogs to mini crème brûlées, it seems that anyone with a great recipe and an enterprising attitude can gain a dedicated Missionite following. Now with the aid of social media outlets like SF Carts Project's Twitter feed, mobile food vendors can update their locations and menus in real time, allowing them to develop customer bases beyond the Mission in locations throughout the city—even if only for a few hours at a time. In addition to their basic function of providing affordable food for the masses, food carts engender a communal atmosphere by bringing locals together in the common act of enjoying a delicious and highly coveted meal. That these carts tend to offer specialties from around the world lends a cosmopolitan flair to even the briefest of lunch breaks. Indeed, food carts have become widely appreciated hallmarks of a truly urban way of life.

DIY: Public Art

Bushwaffle

Photos by flickr users MindTheGap (top) and squash (bottom).

Unlike anything found in most cities' standard street furniture repertoires, Bushwaffle are a squishy, fluorescent antidote to the hard surfaces and drab color palette so commonly employed to furnish urban spaces. Bushwaffle can be inflated anywhere by anyone—allowing city dwellers to form their own impromptu public spaces, and fostering new relationships with each other and the urban environment they share. The portable, temporary nature of these structures relieves the burden of designing street furnishings to withstand weather, vandalism, skaters and whatever else the city decides to throw their way; Bushwaffle inflate when and where needed, and just as easily deflate for future use. A natural choice for outdoor events, Bushwaffle inject a casual playfulness into any public gathering, while also serving as havens for the weary urbanite just looking for a soft place to sit.

Courtesy Rebar.

Art in Storefronts

Ms.Teriosa, by Kelly Ording and Jetro Martinez, installed at 3135 24th St. in 2009. Photo by Cesar Rubio.

Art in Storefronts creates temporary installations of original artwork and murals in vacant storefronts and other derelict spaces in neighborhoods around the city. The program, initiated by the San Francisco Arts Commission, began in October 2009 with installations in Bayview, the Tenderloin, the Mission, and along Market Street; it continued this year with a series of projects in Chinatown. The program, by taking advantage of spaces made available in areas hit hard by the recession, invigorates pedestrian activity along commercial corridors and beautifies the sites, all while giving artists an opportunity to have their work seen.

Off-Site and other projects

Photo courtesy Southern Exposure.

Southern Exposure, a 36-year-old artist-run organization based in the Mission, regularly takes its commitment to local art out into the street. Through its Off-Site program and numerous other public art adventures, the gallery supports artists who take a front-line approach to investigating, interacting with, and influencing the urban environment. For example, the Off-Site series in 2006-2007 included the work of Ledia Carroll, who navigated through the Mission behind a field-line chalker, drawing the perimeter of what was once Logo Dolores, a freshwater lake. The same series featured Neighborhood Public Radio, whose Radio Cartography project used the medium of radio to map public space and engage residents with their environment and with each other. The 2008 exhibition Vapor included a project by Preemptive Media that enabled participants to measure and collect air pollution data in their neighborhoods and share that information with other users city-wide. More recently, the gallery hosted a Hootenanny with the How to Homestead group, which teaches urbanites how to excel at, and revel in, traditionally rural homesteading activities, including folk dancing. Through its work with these artists and many others, Southern Exposure encourages every city dweller to follow suit and become an urban instigator.

Tenderloin National Forest

Photos by Colleen McHugh.

The idea for transforming Cohen Alley, a 136-foot-long stub of street enclosed on three sides by residential buildings and hotels, sprouted in 1989 when Luggage Store Gallery founder Darryl Smith planted a tree in a hole in the asphalt, reclaiming a small connection to nature in a neighborhood known for typifying the worst of urban ills. In 2000 Smith and his gallery co-director leased the alley from the city for a dollar a year, and closed it to traffic. Their vision of a community commons inspired a full-scale makeover, as soil was imported and local residents, students, and artists collaborated to paint murals, lay down brick, and plant trees and vegetables. With a custom-designed gate and walls covered in art, the alley has become a promenade of tiled walkways, grassy areas, gardens, a clay oven, and a display hut constructed using a 6,000-year-old technique of mud and woven strips called wattle and daub. It is home to an eclectic mix of artists, artisans, horticulturalists, teachers, street performers, activists and entrepeneurs—like Michael Swaine, the owner of Sewing for the People, who opens his repair stand once a month in the alley. In 2009 the alley was rededicated as the Tenderloin National Forest, a public space for art and nature that, rare enough anywhere in the city, is a special gem home-grown in the Tenderloin.