The High Line Park in New York City goes beyond the provisional role of public spaces to accommodate human use in surprising ways. Here, a pedestrian overpass frames 10th Avenue, creating an open theater unto city life. Image: Flickr user wallyg

The scene: Mexico City. Destination: internet café. The map says there's one across the Zócalo, an enormous 16th-century plaza several football fields wide.

I take the shortest path cross, a diagonal line. On the other side: Surprise!—a pit of Aztec ruins. Here I spend two hours, lost in a history of platform temple construction and Mesoamerican before—right!—making it to that internet café, where I spend another hour checking my Facebook account and examining a subway map. It was one of those perfectly unplanned experiences that can only happen in a city: a journey that spans time, place and modern technology.

Travel stories are always romantic. But they bring me back to what I love most about cities: the mix of efficiency and serendipity. Cities represent the best of both worlds: the logic of a system, and the prospect of surprise.

But most often, that ratio is out-of-whack, resulting in an amalgamation of over-planned, under-designed places. A few weeks ago, I visited my husband at work in San Bruno, about 10 miles south of San Francisco. The shortest walking route from the BART station to his office park a half-mile away was through a Target parking lot. (This journey inspired little wonder and surprise—and a lot of pedestrian anxiety.) On a paltry sidewalk shoved between the edge of the parking lot and El Camino Real, a busy arterial, I waited impatiently for the light to go red, and for the little man to appear on the crosswalk signal. There I stood between land uses, on the edge of "retail" and the beginning of "office." I was a human afterthought, standing in the margin of a planning document, stuck between circles on a bubble diagram.

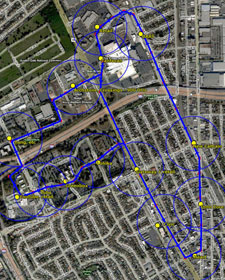

A planning diagram by Cities 21 shows 200-meter "walksheds" in San Bruno, California. Image: Cities 21.

Spaces caught between infrastructure and buildings, like this parking lot in San Bruno, are often ill-fit for human use. Image: Jordan Salinger

Humans are analytical and creative beings, and the places we create for ourselves should be no different. Cities should be useful and pleasurable, appeal to the left and right brains, and work in obvious and surprising ways. Urban planners have the obvious part covered—and by obvious I mean essential. What would a city be without streets, buildings, stores, public transit, sewers—and most of all, people? But how do you plan surprise? How is a city made human? And why are there so many places that feel alienating, as if they were made for a species other than our own?

Making room for modernism

City planning used to be more of a design-oriented profession than it is today. In the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, a period of rapid modernization in cities across the world, grand city plans were a strategy of bringing order and "visual harmony" to the chaotic Victorian city.

On the ground, ideals became real, built into space and paid for with public funds. Requests for city plans were doled out to a sort of visionary Renaissance man (they were exclusively men)—with a background in the arts, design, civil engineering, politics or commerce—much in the same way, it seems, that a patron would commission an artist.

In 1852, Napoleon III hired Georges-Eugène Haussmann, a civil servant who had studied law and music, to draw up a new plan for Paris. Haussmann responded with the imperial scheme Napoleon wanted: swaths of the medieval city cleared to make room for boulevards accented by plazas and monuments. The same concept was employed a half-century later in Washington, D.C., where U.S. Sen. James McMillan formed a commission of three architects and a sculptor to update the plan for the National Mall, originally created in 1791 by Pierre L'Enfant, a French-born American architect who viewed the city as a "work of civic art." The commission opted to double the width of the mall, and incorporated new public monuments, including the Lincoln Memorial.

The heyday for visionary planning ended with the end of Modernism. Today, design fiends look back on the pre- and post-World War II era as a prolific time for American architects, who produced some of the century's iconic houses, furniture pieces and housewares during this period. But their involvement in city planning proved disastrous. Boosted by the previous generation of visionaries, and in response to both the real and perceived threats of urban blight, Modernist architects were given unprecedented power to sweep away older urban fabrics to make room for new urban forms. The results were devastating. In cities across America, entire neighborhoods were razed, often in the poorest areas, to make room for social order, perceived cleanliness and efficiency.

The French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier was such a full embodiment of this spirit, a perfect storm of extreme ego and naiveté, that he seems a near caricature for the movement. Still, Corbusier's stamp on city planning was widespread and real. Through his many writings (he wrote over a dozen manifestos), he was a fervent proponent of minimalism, and stood in firm opposition to decoration and historical pastiche. Conciliation was not his strength; he incited great fury with outlandish statements such as, "The design of cities was too important to be left to the citizens."

In 1925, Corbusier was commissioned by a car manufacturer to create a redevelopment scheme for central Paris. For this commission, which Corbusier named Plan Voisin (after his client), he drew from an earlier project, La Ville Contemporaine, a hypothetical city for 3 million people, in which he proposed a mixed-income community of social elites and blue-collar workers sharing space. In theory, this was a progressive-minded undertaking. But the overtones were blatantly authoritarian: Were the Plan Voisin ever built, the bourgeoisie that Corbusier envisioned living and working in a centerpiece of 66 glass and steel towers would rarely have crossed paths with the proletariat, arranged in rows of low-slung barracks at the city's outskirts. It was the 18th-century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham's "panopticon"—a prison arranged around a central control tower—writ large: a highly controlled and surveilled city for the masses.

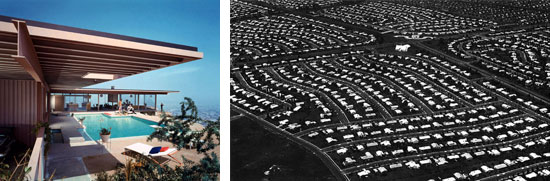

A visual comparison between a Case Study house by architect Pierre Koenig (left) and Levittown, a 17,500-house suburban subdivision built by Levitt & Sons (right), highlights the rarified contributions of Modernist architects versus the purely functional solutions posed by developers in response to the nationwide postwar housing shortage. Images: Flickr user x-ray delta (left); Wikimedia Commons (right)

The limits of aesthetics

Where Corbusier overstepped to squander public trust in the potential for design to shape social outcomes, other architects dabbled. After World War II, more than 3 million men and women returned home to the U.S., and their reunited families had nowhere to live. A good portion rented Quonset huts and temporary housing in former defense areas, or bunked in garages, trailers, barns and chicken coops.

In 1944, Congress approved the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, which allowed veterans to buy homes with government-sponsored mortgages and no money down. More commonly referred to as the GI Bill of Rights, the legislation essentially guaranteed a market for new houses while mitigating the financial risks of large-scale construction. The building industry responded by constructing over 1.5 million single-family houses in two years, and nearly 5 million new homes by 1950.

In response to the housing shortage, architects offered up aesthetics. Style was what architects knew, and what they believed to be the solution. Aligned with advocates for avant-garde style, they operated in a sphere seemingly insulated from the urgency of the crisis.

In 1945, Arts & Architecture magazine launched the Case Study House program, with the ostensible goal of producing house designs that could be replicated quickly and cheaply across America. Over 15 years, the magazine's editorial staff commissioned architects to design 28 houses, mostly in Southern California, in part to assuage their own esoteric fears "that architecture would at the end of the war fall back into its eclectic rut." Although the program was intended to "be general enough to be of practical assistance to the average American in search of a home in which he can afford to live," it never broke through the class barriers separating avant-garde and mainstream culture. Architectural historian Paul Adamson noted, "The program indeed produced beautiful, artistic homes that attracted national interest and thousands of visitors, but no builder was ever able to duplicate any of the designs."

In the meantime, the suburban subdivision was born. Real-estate developer Abraham Levitt and his sons William and Alfred built a 17,447-house development on a swath of Long Island farmland 30 miles outside of New York City. Based on the Federal Housing Administration's concept for a "minimum dwelling," each 624-square-foot house included a kitchen, living room, two bedrooms and one bathroom. By 1947, Levitt & Sons had developed a fully "vertical" construction process, and was rolling out between 25 and 35 houses per day. The popular Cape Cod model sold for $6,990. In Alfred's mind, Levitt & Sons was in the business of serving the public good: "We are constantly criticized because we have sacrificed 'esthetic' [sic] considerations to ease of production, but there's no point in trying to do something unless it can be handed out to the great mass of people as a cultural increase."

I'm not sure I would have disagreed with him. In the public's eyes, the tragedies of Modernism, and the outright success of projects like Levittown, "proved" architects expendable. At the scale of a city, where individual projects can have broad public impact, architects had not proven themselves as capable or trustworthy leaders. Rather, the profession's heavy involvement in postwar "urban renewal"—the displacement of entire neighborhoods to make room for freeways, sanitized public housing developments and new employment and retail districts—had devastated the architectural and social fabrics of cities across America. One of the most widely cited examples of Modernism's failures was the Pruitt-Igoe public housing development in St. Louis. Designed in 1954 by architect Minoru Yamasaki as a series of "vertical neighborhoods" in one of the city's poorest neighborhoods, the project embodied the worst aspects of Corbusian planning. In a series of 33 parallel 11-story buildings, residents lived isolated from each other and the rest of the city. Pruitt-Igoe's tight corridors and poor construction quality made the development a den for crime and vandalism. It was demolished by federal authorities in 1972, not even 20 years after its completion. To this day, it remains an effigy for the failed experiment of Modernism.

These experiments in social engineering (and others like it) backfired so mightily that it necessitated a system of checks on the power architects had to shape city plans. This would forever change the profession, and the ways cities are planned and built. Architects were relegated to the realm of aesthetics, and theorists happily retreated into obscure movements like phenomenology and post-Modernism. And it became the role of the city planner—no longer the Renaissance man with a varied background in the arts, engineering and politics—to facilitate the public process. Planners would navigate new regulatory processes such as the California Environmental Quality Act, and serve as a liaison between project developers, public officials, business interests, community groups and individual citizens. The review process became the core work of urban planning.

Built in 1955, the Pruitt-Igoe public housing development in St. Louis epitomizes the failures of Modernism. Isolated and crime-ridden, the project was demolished by federal authorities in 1972. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Bringing design back to cities

History has good reasons for all but shutting architects out of city planning. It was high time to stop giving them so much leeway and power. But has city planning become less visionary as a result? Have cities gained from talking more and doing less?

It's possible that, just maybe, to cope with the tragedies of Modernism, we threw the baby out with the bathwater. And by sidelining design, our cities are suffering. In particular, the "middle scale" of cities, where planning stops and design begins, needs more attention. These are the places (sidewalks, in front of and between buildings, a path through a park) where humans come eye-to-eye with the built environment. It's the realm of shapes, materials and messages—the specialty of not just architects, but also landscape architects and graphic, industrial and interactive designers.

The middle scale of cities is where the translation of an ideal—say, a welcoming storefront—should be carried out. Too often, these ideals are applied literally, an abstract idea stamped onto space. Designers can help planning here, and in myriad other ways. The next step is creating ways for designers and the design thinking they bring to plug into the process early and often.

Visual thinking. Cities aren't experienced through spreadsheets and lists, so why do we plan them that way? Some empathic visual thinking—imagining and communicating the goals of a project through the eyes of the people most using it—could help shape an analysis in more human terms and lead to different conclusions. It can be reassuring to know an idea hasn't been pulled out of thin air, but sometimes the planning process is so heavy with lists and numbers that the driving vision gets lost. What about more pretty pictures to communicate a vision from the same vantage point from which it will one day be experienced? Sometimes planners avoid using visualizations early on, for fear the project, still in the proposal phase, may seem inevitable (which could hurt their chances of getting it approved). But presenting the public with a vision it can relate to and get excited about could also prove to be politically wise.

This new residential development in Tianjin, China has the ingredients of a great city—housing, sidewalks and open space—but do they amount to a great place? Image: Julie Kim

Working across scales. I've never understood why cities are planned from the vantage point of a bird, or a helicopter pilot. Who experiences cities from the sky? The overall view of cities is, by definition, abstract; no one person can see and experience everything at once. So why not start smaller? Birds-eye views and master plans are important, but they should be coupled with fine-grained, street-level perspectives. Oftentimes these drawings come at the end, as a sort of synthesis of the planning vision. But they could be used for analysis and development, too. What if there were an urban planning equivalent of the way AutoCAD software allows architects to jump scales? That is, a tool that allows planners to toggle between views of a neighborhood master plan and the handrail on a townhouse doorstep.

Viewing constraints as opportunities. Limits aren't a tragedy, they're just the starting point for any project. Designers are so accustomed to hearing about constraints—a narrow site, paltry budget, strict aesthetic guidelines—that they don't get turned off or even fazed by them. Sometimes it's actually helpful to have the physical or conceptual boundaries of a project defined; I've heard a lot of architects say, without a hint of irony, that it makes their work interesting. (No doubt they can be a masochistic bunch.) Planners have a lot to learn from this attitude toward constraints. If the planning process deals you a blow, it may be better to accept it and push the project team to turn it into an opportunity, rather than fight it to the death. In the end, the project could turn out better, though not in a way you or anyone else had imagined. The result: surprise!

Paying attention to details. In the same way architects obsess over handrails, power outlets and the degree of swirliness in a concrete floor, planners need to insist on perfecting the details of a city's public spaces. Comfortable park benches, clearly labeled trash cans, the right spacing and species of trees, bike lanes with infographics that can be understood in a split second. These are the details that facilitate use, comfort and pleasure on sidewalks and streets and in parks and plazas. Last year, SPUR's committee on privately-owned public open spaces rigorously examined 68 of San Francisco's POPOS, commenting on everything from seating, shading and public art to signage and materials. This level of meticulousness should be applied to our public open spaces as well.

Translating ideas—and ideals—into space. This can be tricky, and there are many examples of it going wrong. The New Urbanist movement, for example, sets out to create walkable mixed-use communities. What's not to like? But the ways these ideas are implemented leaves a lot to be desired. For instance, why are New Urbanist communities often modeled after 19th-century American towns? Why all the nostalgia? Are the answers really in the past? Designers often start projects with an inspiration—an idea, object, image, material—that originates in nature, art or someone else's work. But the translation of this inspiration into something new is where the hard work happens. As in literature, the best translations are nuanced, not literal. More of this kind of creative willfulness could help generate new versions of walkable communities that are of our time and place.

Small design cues, like this greenery peeking up above the edge of the High Line, can inspire curiosity and generate surprise in cities that might otherwise feel overly planned. Image: Julie Kim

Iterating, and being usefully wrong. Iterative thinking is crucial to design, and should be more integral to planning. The problem and the beauty of continually testing ideas is that the process rarely moves in a straight line. (In that sense, an iterative approach defies the sequential nature of planning, which is often structured as a slow march toward approvals.) Instead, in an iterative design process—"ideating" is the term coined by IDEO co-founder David Kelley—project phases overlap and there's opportunity for findings from a later stage (prototype development, for instance) to inform an earlier stage in the process (such as research and analysis). If this model were applied to urban planning, we'd first need to soften the hard line between the planning and design phases, and between the professions. The development process is set up for planning to come first and to shape design. If the process were changed to be more iterative, there could be more cross-pollination, and design could inform planning in the same way planning informs design.

Like a good shrink, design thinking can free urban planning from its tendency to over-analyze. It could balance the left- and right-brained aspects of citymaking, and introduce some whimsy into the planning profession's over-emphasis on logic and efficiency. "Nobody wants to run an organization on feeling, intuition, and inspiration, but an over-reliance on the rational and the analytical can be just as risky," IDEO CEO Tim Brown and Social Innovation Director Jocelyn Wyatt wrote in a recent issue of the Stanford Social Innovation review.

The same can be said for cities. Can we use design to make planning visionary once again? And perhaps, more personal? City planners, architects and policy analysts already do a great job of making our cities work. We need and are lucky to have them all. But cities aren't experienced through spreadsheets or lists, or from a plane. They're experienced through design. And that's how we should plan them.