The story of downtown Washington, D.C.'s revitalization is about more than resurrecting a languid office district that now rivals the dynamism and economic success of New York, San Francisco, Boston, London and Tokyo. A perfect storm of converging forces took hold in the late 1990s and propelled the downtown area toward an economic crescendo in 2007. Today, a district that once resembled a desolate office park — with acres of parking lots and derelict buildings — has evolved from being dull, dirty and dangerous into a 24/7 environment anchored by a thriving office market and energized by new housing, retail, theaters, restaurants and museums.

How did this happen? It took a committed business community, the political will of City government and a renewed interest from the federal government in its home city.

HARD TIMES FOR D.C.

In some ways, the story of urban decline is not particular to D.C.: after World War II, the City faced huge demographic and cultural shifts — a problem for most American cities during the same period. But D.C. planners were also weighed down by obstacles of their own making, some the result of its complicated relationship with the federal government.

From 1955 through 1995, D.C. faced the loss of its middle-class tax base. As residents fled to suburbia, they sought things not offered in the city: lawns and two-car garages, shopping malls, lower taxes, better schools and government services. In D.C., the damage from the 1968 riots was so severe that many downtown and neighborhood businesses never reopened.

The City also made a host of fateful bad decisions. First, upon receiving self-governance in 1974, the City accepted an unfunded pension liability — amounting to $300 million — for federal workers who became City employees. That amount ballooned to $4.5 billion in 1997 (when the federal government assumed this liability). By the late 1980s D.C. had become known as the "murder capital of the world." The arrest of the mayor in 1990 for drug use fueled this perception of a risky investment environment. The national recession in the early 1990s dealt the final blow, further weakening what was already a depressed economy. A successful 1990 rezoning effort that created today's thriving mixed-use section of downtown further depressed real estate values in the early 1990s.

Over this same period of time, the federal government, the City's primary employer, remained indifferent to the city it called home. In 1963, Congress ordered D.C. to replace its 210-mile streetcar system with buses. The construction of Interstate 395 in and around downtown, and a federal "urban renewal" plan in the southwest, severely damaged the city's original street grid, leading to bleak neighborhoods. The Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation (1972-1995), a quasi-public entity created by Congress, received inconsistent federal funding — not enough to create a critical mass of redevelopment that would become self-sustaining, but enough to create a culture of dependency in D.C. on the federal government for transformative downtown investment. The decision of some federal agencies — including the Patent and Trade Office, the Food and Drug Administration and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) — to move their operations to the suburbs contributed further to the city and downtown's decline. Even the construction of D.C.'s subway (an excellent long-term investment) had negative short-term construction impacts on local business. Finally, the federal government owns 40 percent of the land in D.C. but pays no property tax — the City has responded by raising commercial property and corporate income taxes to balance its budget. On the positive side, the federal government supported the Smithsonian, other museums and the Kennedy Center — all regional, national and international tourist draws.

By 1995, downtown D.C. had languished from years of neglect. Too many properties sat vacant. Its most prestigious department stores, Garfinckel's and Woodward & Lothrop, were closing their doors. In 1995, the downtown area's 120 commercial blocks had 70 surface parking lots and 50 vacant or boarded-up buildings. The future looked bleak.

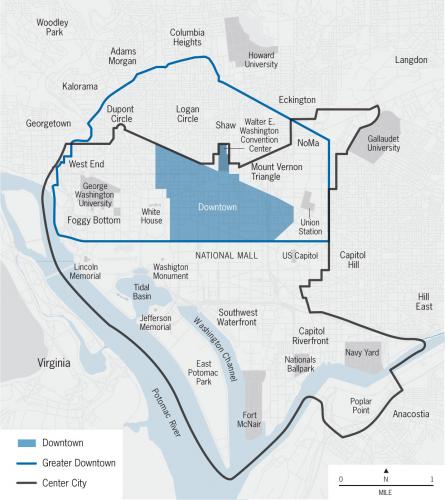

Since 1997, the downtown area of Washington, D.C. has experienced solid population and job growth. Downtown now generates 23 percent of the city’s tax revenue and has a net fiscal impact $797 million (roughly the same as the city’s public school budget). Following on this success, developers, the City and the federal government are working to make investments in the emerging markets of the Center City.

THE GREAT TURNAROUND

In the mid-1990s, business and civic leaders planned and pushed for both a new downtown sports and entertainment arena and the establishment of a downtown business improvement district stretching from the White House to the Capitol Building. The goal was to produce a "living downtown" to complement office buildings with more housing, culture and entertainment. In 1995, ground was broken for the new arena. In 1996, the mayor and city council enacted a Business Improvement Districts Act to help rejuvenate neighborhoods and spur economic development. The Downtown Business Improvement District (BID), the city's first BID, began operations in November 1997.

In December 1997, the revitalization of downtown D.C. began in earnest. The plan for the $300 million MCI (now Verizon) Center was the first big, transformative project that helped to catalyze more development downtown. The City contributed $100 million to this project in the form of a below-market land lease, property tax abatement and by issuing bonds for the construction of a new subway entrance adjacent to the arena that were supported by a new temporary gross receipts tax on D.C.'s larger businesses. The Center's opening drew record crowds, attracting sports fans from every ward of the city as well as suburbanites, who returned to the inner city for the first time in years.

The City also had the support of the Clinton Administration. The National Capital Revitalization and Self-Government Improvement Act of 1997 enabled financial recovery as the federal government assumed the City's $4.5 billion unfunded pension liability, and agreed to increase the City's Medicaid reimbursement rate to 70 percent from 50 percent in exchange for a reduction of the federal government's annual payment from $660 million to $190 million.

In 1998, the D.C. government approved the construction of a new convention center, completed in March 2003. The City contributed $40 million of land to the project, and the hotel and restaurant industries agreed to new taxes to fund its $850 million construction. The City's non-voting member of Congress, Eleanor Holmes Norton, achieved many successes retaining and attracting federal agencies. The federal government's planning agency, National Capital Planning Commission, began to support plans for the revitalization of downtown rather than focusing solely on the needs of the federal agencies. NCPC assisted in the development of D.C.'s circulator bus system in the early 2000s, and developed the National Capital Framework Plan in 2007-2009 for the areas of the city around the National Mall, including suggesting a new use for the site of the FBI headquarters building.

The city's new image and policies of the late 1990s, under Mayor Anthony Williams, supported business development, which enabled significant employment and population growth. A wide array of business sectors, including legal services, international banking and finance, management services and communications continued to grow and create new jobs. Many of these employers were responding to market globalization, and located in D.C. as a lower-cost alternative to New York or London. With the improvement in the City's financial condition, the mayor and the city council were able to implement modest tax relief under a program of "tax parity" with surrounding jurisdictions.

Downtown D.C. has lost approximately 22,000 federal jobs since 1990, but has experienced a gain of 6,000 jobs since 2005. Meanwhile, growth of federal government jobs and federal government “support” jobs (profession and business plus information and technical services) in Virginia and Maryland suburbs has been steadily rising since 1990.

The City and downtown business leaders created a Downtown Action Agenda in 2000 that set goals for the growth of downtown.1 Several tools were used: preferred uses on City-owned land, tax increment financing, tax abatements, arts grants and zoning changes. The key to all these projects was in-depth economic analysis to make the case that strategic investments by the City were (1)necessary to build a critical mass of economic activity in order to be self-sustaining, (2) likely to accelerate other development by several years, and (3) had a positive return on investment for the City by producing new future tax revenues. This required bringing City staff and officials together with developers to go over their financial models in detail. The collaborative spirit of these public/private partnerships was partly the result of both the public and private partners having experienced together the difficult days of the early and mid-1990s. To date, the City made net economic development investments in downtown of approximately $300 million in projects totaling $2.3 billion, and total downtown private investment has been approximately $10 billion.

To fufill D.C.'s ambitious social agenda, Mayor Williams and current Mayor Adrian Fenty invested heavily in social development — hundreds of millions of dollars in affordable housing, job training and public school renovation and new construction — and in neighborhood economic development projects to assure an equitable social contract for D.C. In 2008, Mayor Fenty announced the Center City Action Agenda, which builds on the achievements of the 2000 Downtown Action Agenda by establishing a $400 million economic development investment plan to realize similar development and place-making goals in the undeveloped areas of D.C.'s emerging Center City.

To complete and maintain the revitalization of downtown D.C. and extend its development momentum to the entire Center City area will require more work and continued public/private partnerships. In particular, to continue to attract private and federal government capital and partnerships, D.C. needs to maintain its investment in economic infrastructure and amenities (in balance with its important social investments), and continually monitor its competitive position in the metropolitan marketplace (and take action when necessary). Only in this manner will downtown and the emerging Center City area continue to evolve into a remarkable urban experience for all D.C. residents, workers and visitors while contributing significant financial resources to the City's robust social agenda.

ENDNOTES

1The Downtown Action Agenda created 6,000 new apartments or condominiums; 215,000 square feet (SF) of retail; 50 new restaurants; two new live theatres (1,032 seats)1 992 new hotel rooms; and 10 million SF of new office space.