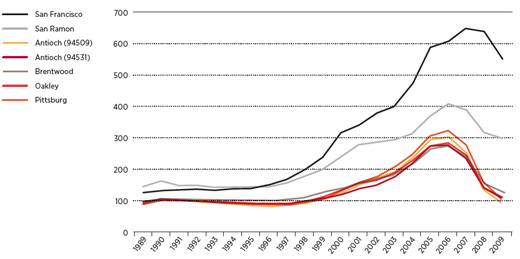

In the wake of the City of Vallejo’s bankruptcy, and the now-global attention focused on Stockton, Northern California has emerged as a center of deep questions about the solvency of American cities. The factors contributing to fiscal stress are numerous, including spending habits and questions of labor contracts and public safety costs. Fiscal stress varies among communities in the Cities of Carquinez but the contribution of rapid growth during the post–Proposition 13, post-Reagan era must be considered in any understanding of fiscal challenges. Antioch, which grew from a small city of just over 40,000 to more than 100,000 people between 1980 and 2010, provides an instructive example, as it came perilously close to bankruptcy in the wake of the crisis and is still coping with a major reduction in city services that was unthinkable a generation ago.

As Schafran alludes to in his article, “The Cities of Carquinez,” planners in the 1970s assumed that areas like the greenfields of eastern Contra Costa County wouldn’t be developed without access to regional, state and federal funding for “growth-inducing” infrastructure. In reality, these cities, including Antioch, used a variety of creative, and ultimately unfortunate, local financing mechanisms to pay for infrastructure improvements. Antioch was an early adopter of Mello-Roos, a property tax–based financing mechanism that it used to pay for the development of new schools. Impact fees charged to developers were established to pay for capital projects, including sewers, local roads and more. Antioch also joined forces with the neighboring cities of Pittsburg and Oakley, as well as Contra Costa County, to establish a regional impact fee to fund road and highway improvements, particularly for Highway 4, the lifeline that connects drivers to the rest of the Bay Area. These fees added tens of thousands of dollars to the sales price of each new residential unit.

When the housing market crashed in 2006, these funds dried up, leaving many capital projects with large shortfalls and no funding source in sight. A series of short-term bargains, meant to incentivize new home construction in the near term, will leave these cities — and ultimately their residents — responsible for project costs they just cannot afford.

For those capital projects that were actually completed during the boom years, it will be difficult to find the general revenues needed to pay for their ongoing operations and maintenance. Like many cities throughout California, before the 1978 passage of Proposition 13 businesses and local industry were the largest contributors to Antioch’s local revenues. But the combination of a cap on property taxes and the lack of new job growth shifted the cost burden to homeowners, who now need to pay more just to keep the same level of services, exacerbating inequalities between older and newer residents. And these cities’ revenues have become highly dependent on (severely declining) home real estate values.

Antioch is more reliant on residential property taxes than the average California city, which made revenues particularly vulnerable to the bursting of the housing bubble. But Antioch is not alone in this story, nor is Vallejo, whose bankruptcy is well known. Pittsburg’s plan to build an eBART station at Railroad Avenue is rapidly fading without local funding. This is just one of innumerable stories of strained fiscal models in jurisdictions that became dependent on residential growth.

Racial/Ethnic Composition, Bay Area, 2010

Since 1980, the African-American population in the Cities of Carquinez increased from under 35,000 to nearly 100,000, reflecting an increase in the subregion's share of the region's black population from 7 to 21 percent. During the period from 1980 to 2010, the African-American population in San Francisco declined from 86,000 to less than 50,000, and in the inner East Bay, from 220,000 to less than 160,000. The population center of African-Americans in the Bay Area is increasingly shifting towards the Cities of Carquinez. Although less than 15 percent of the total population of the Cities of Carquinez is black, over one in five of the region's black residents live there.

Part III: Economic Opportunities

Despite an early history as a major industrial and manufacturing hub, the Cities of Carquinez have become a series of bedroom communities stuck in an economic development cul-de-sac. Compared to the wider Bay Area, area workers face few local job prospects, limited transportation options to connect them to jobs elsewhere in the region and scarce social service and job training programs to support entry (or reentry) into the workforce. These last two factors impact the ability of local leaders to bring jobs to the area, despite available land.

While the population in the Cities of Carquinez grew by nearly 70,000 people from 2000 to 2010, only about 7,000 jobs were added — about one for every 10 new people. Compared to the Bay Area overall, a large portion of these jobs (nearly one in four) are in low-wage retail, entertainment and hospitality sectors. The region is also more reliant on public administration and education, both of which have faced severe layoffs during this recession. Though nearly one in six jobs (15.1 percent) in the Bay Area are in the technology, science or information sectors, these sectors make up only one in 22 jobs (4.5 percent) in Carquinez.

With few local prospects, nearly 80 percent of the eastern Contra Costa workforce commutes out of the area to work. Limited public transit options leave these workers with little choice apart from car commutes that average more than 40 minutes, some of the longest in the Bay Area. Not surprisingly, a recent study by the Center for Neighborhood Technology [

www.cnt.org] shows that Carquinez has some of the highest housing and transportation costs in the Bay Area, even though median household income is about 13 percent below the Bay Area median.

Echoing trends throughout the state and country, poverty in these metropolitan-edge communities is on the rise. Over the last 20 years, the poverty rate in the Cities of Carquinez has grown twice as fast as in the state overall. In unincorporated Bay Point, one in four families are now below the poverty line. Inadequate social services in the area make it exceedingly difficult for local residents to access the workforce training, housing assistance or health services that can help them successfully enter or stay in the workforce. For every $1 in local social services to which a poor person in eastern Contra Costa County has access, $8 is available to a poor person living in western Contra Costa County. [1]

This imbalance is part of the larger infrastructure gap facing leaders and residents in Carquinez. A generation ago, regional leaders knew that growth would happen in this area, but the political will to plan for it, to ensure that the transportation, fiscal, social services and economic infrastructure needed to make this growth financially, environmentally and socially sustainable was never present. And like the map of regional inequality a generation ago, this new map is heavily racialized.

PART IV: Racial and Ethnic Change

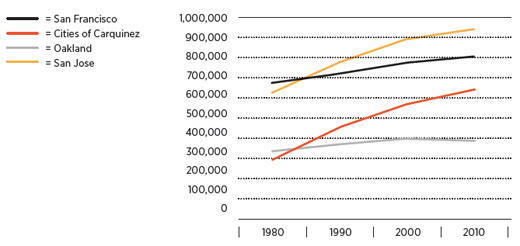

Over the past 30 years, the population has exploded in the Cities of Carquinez, especially compared to slow-growing San Francisco and Oakland, and has kept pace with the growth of San Jose, which started off as a much larger place. This growth was exceptionally ethnically and racially diverse, and today Carquinez is now more black and Latino and less white than the region as a whole.

The number of Latinos has increased so rapidly in Solano and eastern Contra Costa counties that by 2000, this region had become a larger center of Latino life than San Francisco, whose Mission District is renowned as perhaps the most famous cradle of Latino culture, art and political activism in the entire Bay Area.

Even more dramatically, the African American community in San Francisco has decreased in absolute numbers even as it has skyrocketed in the Cities of Carquinez. It would be misleading to assume that most African Americans who have left historically black neighborhoods such as the Fillmore District and Bayview-Hunters Point in San Francisco have moved directly to Carquinez (although many certainly have). African Americans have long staked a strong claim to a number of locations throughout the Bay Area, most notably Oakland and the rest of the East Bay urban core (defined here as Richmond, El Cerrito, Albany, Berkeley, Emeryville, Oakland and Alameda), but also East Palo Alto, Marin City and others. These places are linked in a chain, and significant migration between them by African Americans, whether native to or newly arrived to the Bay Area, continues.

While San Francisco and the East Bay urban core remain important, these and other traditional locations have greatly decreased in population relative to newly emergent subregions. South Alameda County (defined here as comprising San Leandro, Union City, Fremont and especially Hayward) has emerged as an important new nucleus of African American life. But no subregion has arisen as rapidly as the Cities of Carquinez, which are now home to 21 percent of the Bay Area’s black population, up from just 7 percent in 1980.

The picture for Asian Americans is less dramatic, since the Cities of Carquinez’s share of Asians and Pacific Islanders has remained roughly constant at 5 percent from 1980 to 2010 even as their overall numbers almost quadrupled in the Bay Area. But that picture changes when we look at particular groups falling under the broad and highly diverse category of “Asian American.” Filipinos, a community with deep roots in the Bay Area, have joined Latinos and African Americans in blazing a trail to the Cities of Carquinez in recent years. By 2010 the Carquinez Filipino community of over 54,000 outnumbered its San Francisco counterpart by more than 15,000 people.

Part V: Embracing Diversity

We have highlighted racial and ethnic diversity in this paper because the fiscal, economic and transportation struggles in Carquinez are very real, and the fact that these communities are more black, Latino and Filipino than the region as a whole is all too reminiscent of the dark days of the Bay Area past. We have much to be proud of in this region, but we have also promulgated some of the worst abuses of exclusionary zoning, urban renewal and restrictive covenants, and we must see the challenges of Carquinez in light of this history.

To their credit, many environmental, smart growth and affordable housing advocates tried valiantly to prevent unsustainable patterns of growth in these cities, but it remains an open question whether they or any other regional actors truly came to grips with the profound legacy of racial inequality in the region. If we as a region are committed to long-held goals of sustainability, we must acknowledge how yet again race has played a role in the development of an unequal Bay Area.

It is also an open question to what extent the communities of Carquinez, and those organizations in the Bay Area who struggle for racial and economic justice, have truly embraced this new and colorful regional geography. Solving the problems of Carquinez means embracing Carquinez's diversity and the fact that it is now an important center of African American, Filipino and Latino life, a network of cities central to an equitable and multicultural future in the Bay Area.

--

[1] Western Contra Costa County includes the cities of Richmond, San Pablo, El Sobrante, Hercules and Pinole. This measure does not include government-provided services or services provided by satellite offices of regional nonprofits based elsewhere. While including these factors may reduce the disparity, it is unlikely to eliminate it altogether.

Correction: In the print edition of The Urbanist, the Center for Neighborhood Technology was incorrectly referred to as the Center for Neighborhood Studies. We regret the error.