Shanghai is the pinnacle of Chinese economic development and a good reflection of where the entire country is headed if growth continues. The city is now middle-income and has a diversified service economy — and, despite wage growth, its per capita savings rate is decreasing as residents spend more money on housing, consumer goods and other services. The city produces 100,000 college graduates per year and nearly 30 percent of its residents have a college degree (double the rate of a decade ago) [1]. And though the region maintains a strong, globally competitive manufacturing base (building products like the new eastern span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge), the economy is shifting away from export-oriented manufacturing and toward high-end services like finance, technology and business services. Several of the sites SPUR visited were adaptive reuses of manufacturing spaces, including a former auto parts factory that now houses the Shanghai office of architecture firm SOM, among other businesses, and an art deco slaughterhouse currently occupied by several arts organizations.

These economic changes are giving rise to greater income inequality, rising housing costs, longer commutes and increased car-ownership rates. There are also more than 8 million migrants from rural China who lack official papers to work in Shanghai yet still need jobs and housing. Maintaining an economy that produces jobs for the masses while simultaneously increasing per capita incomes and moving local industries to higher-value activities (which are often less labor-intensive) is a delicate and risky balancing act.

But this process is made easier by the fact that Shanghai is not just a city but a region, with a mayor who presides over all of the various districts within it. This makes regional coordination much more effective, as it occurs within a single governmental jurisdiction.

To better understand economic development in Shanghai and draw lessons for the Bay Area, let’s look at recent changes in two distinct parts of the Shanghai region: Jiading and Pudong. Jiading is a “new town” (a master-planned city built from scratch in a previously undeveloped area) 20 miles from the center of Shanghai with a focus on the automotive industry. It is one of nine new towns in the Shanghai area, each planned for a population of 800,000 to 1 million. Pudong, the eastern district of Shanghai, was designated a national economic zone in 1990 and is renowned for the futuristic skyscrapers in its Lujiazui District, which lies directly across the river from Shanghai’s famous early-20th-century promenade, the Bund.

To put these two districts in a Bay Area context, Jiading would be like building a totally new city of 1 million people in the Livermore Valley, with its own district mayor accountable to a regional mayor. Pudong’s Lujiazui District would be as if the U.S. government decided to make the former naval station at Alameda Point into the country’s leading financial center and created a free-trade zone there with tens of millions of square feet of office space while preserving downtown San Francisco as a quaint, historic employment and retail center.

Jiading: Decentralizing growth to “new towns”

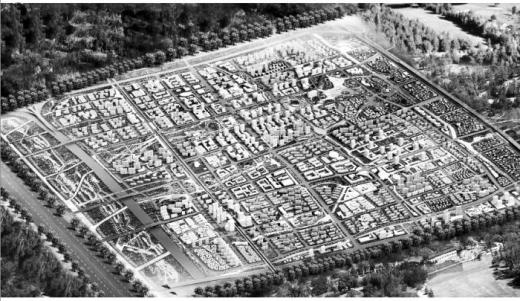

Once a relatively undeveloped area of farms and small villages, Jiading has been transformed in the past decade with new office and residential towers, factories, schools, parks and roads. As a designated “new town,” Jiading reflects Shanghai’s policy of decentralization, shifting new population growth and existing industry away from the region’s city center (which will remain at 10 million people). Much new growth will be distributed to nine new towns of up to 1 million people, as well as 60 smaller cities of approximately 100,000 people.

With new towns like Jiading, the Chinese government is shifting population growth and existing industry away from Shanghai’s city center. Like much contemporary Chinese urbanism, the plan for Jiading emphasizes wide boulevards, mega blocks and towers set back from the street.

With an economic focus as Shanghai’s “Automotive City,” Jiading is the largest automotive district in China. Home to the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation, which partners with Volkswagen and General Motors, Jiading manufactures hundreds of thousands of cars each year. Low taxes are key to this success. Profit taxes are as low as 15 percent for firms that use new technology, establish an R&D facility or are the regional headquarters for a global company. But in an attempt to avoid the fate of U.S. manufacturing centers like Detroit, Jiading’s district mayor, Sun Jiwei, says the new town is moving away from a narrow manufacturing emphasis to embrace “upstream” activities (like research and design) and “downstream” activities (like marketing and testing) and capture the broad value chain of the automotive industry. In addition to the assembly plants, Jiading has attracted more than 100,000 related companies in industries such as components manufacturing, logistics and after-sales services. Its big attraction in downstream activities was the building of a Formula 1 race track. Jiading’s next strategy is to move upstream to capture auto research and design firms as well as those in related sectors like industrial design, electronics, information technology and electric car batteries.

Jiading’s focus on cars reflects a national strategy to decouple future growth from exports. Since the global economy is slowing, China increasingly has to rely on its internal markets for future growth.

While cars provide an engine for job growth, it is real estate development — led and managed by local government — that provides the funds to offer the lucrative tax breaks. The government, which owns all property, sells development rights and then requires developers to sign long-term leases: 70 years for residential, 50 years for industrial and 40 years for commercial. These stable annual revenues fill local government coffers and provide the funds for a range of investments, from infrastructure to government-run companies to tax breaks for private firms.

As noted above, real estate development is often the means to an end, which is to meet a target for gross domestic product (GDP). Each level of government contributes toward national, provincial and local GDP goals. Local officials (most of whom are trained as engineers or economists) must meet these targets or risk losing their jobs. This provides strong motivation for an effective economic development strategy.

Pudong’s Lujiazui District: Reclaiming Shanghai’s status as a global financial center

In the early 20th century, Shanghai was the world’s third-largest financial center after New York and London. But after the Chinese Revolution, financial services ceased to be a major industry in Shanghai. Today, Pudong reflects the city’s — and country’s — desire for Shanghai to reclaim a global role in finance and wrestle the regional title away from Hong Kong.

In 1990, the national government declared much of the land east of the Huangpu River the Shanghai Pudong New Zone. Firms that locate there pay no duties or income taxes, and (since 2001) foreign companies can open financial institutions that use the local currency, the renminbi. The area houses the Shanghai stock exchange, which comprises 87 percent of China’s national stock market.

As a result, Shanghai receives about a quarter of the entire country’s financial-services investment. Pudong currently has more than 12 million square feet of Class A office space — more than half of all such space in Shanghai — and an additional 5 million square feet is under construction.[2]

Photo by Egon Teplan. Inspired by La Défense in Paris and other monumental districts, Pudong emerged out of agricultural land to become the nation's financial center and home to millions.

The success of Pudong reflects Shanghai’s shift toward a service economy. In 1990, 60 percent of Shanghai’s employment was in manufacturing, 38 percent in services and the rest in agriculture. By 2005 this had reversed: Services now make up 60 percent of the Shanghai region’s economy and as much as 75 percent of the economy in the city center.

Pudong also reflects the national government’s belief in urbanization and infrastructure development as the best ways to achieve GDP growth. Pudong has the region’s international airport, major port facilities and the world’s only commercially operating Maglev train. (The train is mostly a disappointment, however, in that it was intended to link to the city center but in fact terminates at a distant edge of Pudong, where travelers still have to transfer to taxis or the metro.) Infrastructure in Shanghai has averaged approximately 10 percent of GDP during the past decade.

Concluding lessons

If Shanghai reflects China’s success at economic growth, what lessons can we apply to the Bay Area? Given obvious differences in our cultures and governments, making comparisons is risky, but a few lessons emerge:

1. Because the majority of the region is under the jurisdiction of one governmental entity, Shanghai municipality, there is consensus for where to locate and how to support targeted industries such as finance and automotive. This means overall regional economic growth can happen much faster.

2. Local officials’ career success is measured by their ability to meet regional targets, such as increasing the GDP. This provides a strong motivation to develop and implement an economic strategy that actually works.

The struggling Bay Area economy could benefit from a regionally drafted economic strategy and elected officials willing to support growth where it best serves the region (even if that means some places get greater focus than others). Our government is not going to set GDP targets for all elected officials, but perhaps we could use more local leaders with the political fortitude and regional perspective to support what is best for the entire Bay Area, not just for their own community.

[1] Preparing for China’s Urban Billion, McKinsey Global Institute, March 2009. www.mckinsey.com/mgi/reports/pdfs/china_urban_billion/China_urban_billi…

[2] Cushman and Wakefield, Q1 2011. http://rightsite.asia/sites/rightsite.asia/files/shanghai_off_1q11.pdf