San Francisco is famously among the world’s most beautiful cities. But saying a city is beautiful is a bit like saying a person is “nice” — it’s a gloss over the rich particularities of identity and character.

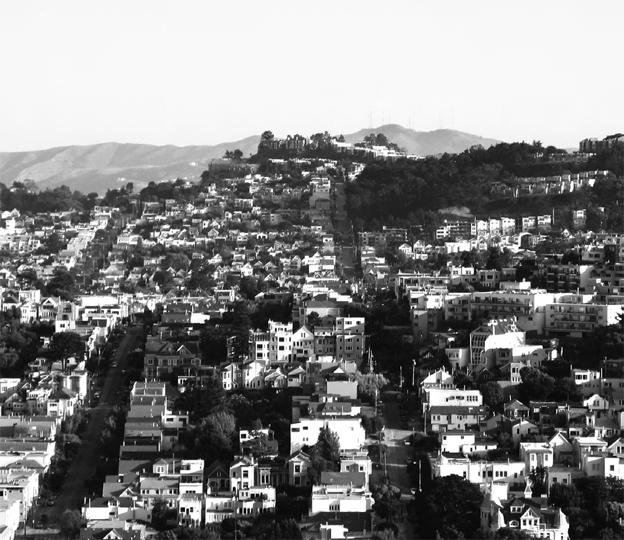

This city’s unique magnificence resides in the long and middle distance. Its iconic views are from hilltop to hilltop, of fog cascading over piles of white cubes diced up by a perfect grid that seems to amplify the topography by ignoring it; of the city’s incomparable natural setting — of ocean and headland, bay and mountain — seen from the Presidio, the bridges, the islands. It’s as if we understand San Francisco best by getting out of it, or above it, and looking back at it.

Closer in, the city boasts a unique cornice line — the boundary of building and sky — with a rhythm of crenellated bays that is passed from building to building, giving the San Francisco street a kind of frilled collar that may be its best feature.

But get down into the foreground — into the street itself — and San Francisco can be downright nasty. Up close, more than we tend to admit, this city is hard, cold, gritty and loud. It is a foreground that we seem content to tune out as we marvel at the city’s renowned vistas. Allan Jacobs once said that when he arrived in San Francisco from Pittsburgh to take over as planning director, he was struck above all by the barren nature of the streets. How is it that a city as wealthy and progressive as San Francisco tolerates such an impoverished public realm?

The Public Realm

Mention public space, and most people will picture parks and plazas — purpose- built gathering spaces at the center of city life and identity. But streets — or more precisely, the portion of them devoted to sidewalks — are by far the predominant form of urban public space.

Destination spaces alone can provide delightful nodes of sociability and respite, but a vibrant public life requires a continuous public realm — a network that extends to and from each citizen’s front door and enables all the basic functions of life to occur in collective settings. Only streets can provide that kind of connective tissue, and ours — rightly criticized as overwide, car-dominated and bereft of trees — are falling far short.

Streets can provide some of the most graceful and humanizing spaces in a city — think of Dolores Street, Noe Street in the Duboce Triangle, Claude Alley — but they must also accommodate a host of other burdens: moving cars, bikes, buses and trains, access to private buildings, on-street parking, stormwater management and utility lines, all competing for the same limited space.

It’s not that this city lacks a public realm, but San Francisco truly belongs to pedestrians only in pockets. In a handful of core districts — Union Square, the Financial District, North Beach — the crush of people, swollen by a torrent of visitors, is sufficient to tip the scales in favor of people and away from the ubiquitous challenges of car traffic, the chilly climate and a lifestyle that (relative to other major cities) favors private pleasures over public ones. Neighborhood retail streets — think Hayes Street, West Portal Avenue, or Irving Street, among many — provide another constellation of vital public destinations. What’s needed is a better network of ordinary background streets to tie these wonderful places together.

The building-street interface

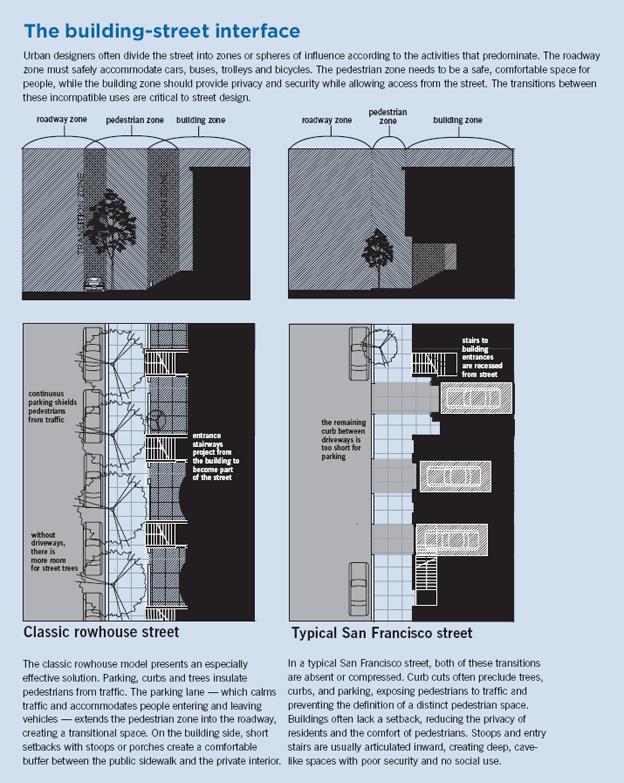

Urban designers often divide the street into zones or spheres of influence according to the activities that predominate. The roadway zone must safely accommodate cars, buses, trolleys and bicycles. The pedestrian zone needs to be a safe, comfortable space for people, while the building zone should provide privacy and security while allowing access from the street. The transitions between these incompatible uses are critical to street design.

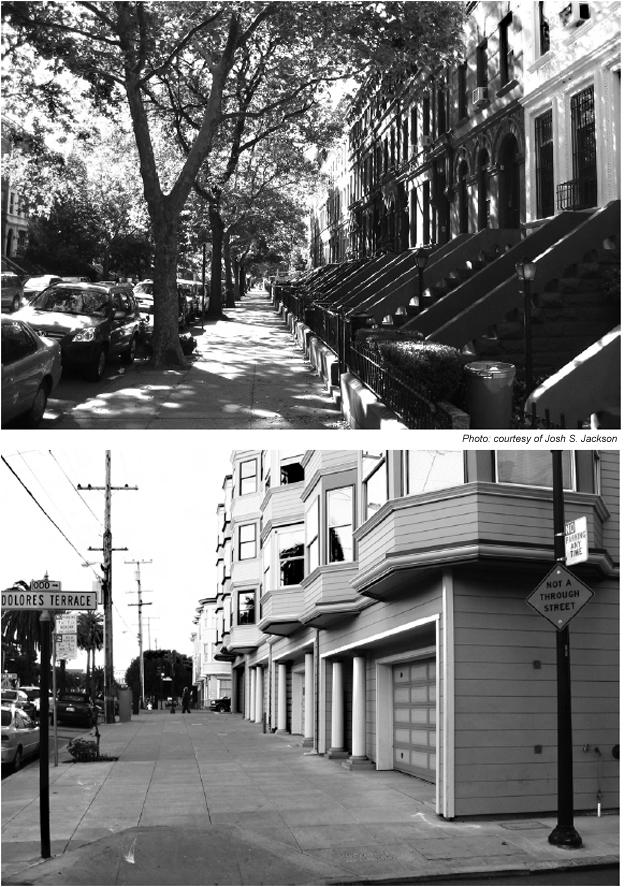

The classic rowhouse model presents an especially effective solution. Parking, curbs and trees insulate pedestrians from traffic. The parking lane — which calms traffic and accommodates people entering and leaving vehicles — extends the pedestrian zone into the roadway, creating a transitional space. On the building side, short setbacks with stoops or porches create a comfortable buffer between the public sidewalk and the private interior.

In a typical San Francisco street, both of these transitions are absent or compressed. Curb cuts often preclude trees, curbs, and parking, exposing pedestrians to traffic and preventing the definition of a distinct pedestrian space. Buildings often lack a setback, reducing the privacy of residents and the comfort of pedestrians. Stoops and entry stairs are usually articulated inward, creating deep, cave-like spaces with poor security and no social use.

Curb cuts are a defining element of San Francisco streestscapes. Driveways eliminate the buffers provided by an intact city street: the sidewalk, on-street parking and trees.

The Classic Rowhouse Model

The classic model for this relationship flowered most fully in the 19th century, as fast new roads made sidewalks essential and wealthy burghers demanded elegant housing in town. A look at this classic model reveals a great deal about how streets and buildings can work together to support the public realm, while allowing for both privacy and mobility. Its legacy is visible in beloved urban neighborhoods such as London’s Chelsea, Brooklyn’s Park Slope, Boston’s Back Bay, and Washington, D.C.’s Mount Pleasant: a common pattern that integrates flats or rowhouses with remarkably livable streets.

In these classic neighborhood streets, pedestrians are insulated from the roadway by on-street parking, a continuous curb, and a row of trees, light poles and other streetscape elements. These three different buffers provide a strong outside edge to the sidewalk that is nevertheless visually and physically permeable.

On the building side, a short but consistent setback establishes a buffer between residential units and the public sidewalk, punctuated at regular intervals by stoops, paths or porches. Ground floors are usually raised, typically by a half level. The setback zone not only provides a buffer, it also becomes a multipurpose space in itself. Stoops and porches create the kind of sociable overlook described by Jane Jacobs, from which residents can see up and down the block, watch the world go by, greet their neighbor, keep an eye on the kids. The spaces between stoops can be used for small gardens, workshops, entrances to basement units or even just to store trash cans.

These features introduce what Oscar Newman refers to as “symbolic boundaries” — underscoring the privacy of the residence while maintaining a strong visual and functional connection to the street. Together they create a privacy gradient: from the entirely public sidewalk to the stoop, which (although it is private property) anyone may use to approach the entrance, to the front door, which is the threshold of the entirely private interior. As Newman articulated in his classic book “Defensible Space,” the visibility of these inviting transitional spaces also creates natural surveillance of both the street and of building entrances.

On both sides of the pedestrian zone, this classic model allows a transitional space for the street’s functional zones to overlap and interpenetrate. Street parking, in addition to calming traffic and providing an edge to the sidewalk, extends the pedestrian zone into the roadway as people enter and leave their cars. Setbacks with stoops enhance privacy while devoting private property to the social and physical enhancement of pedestrian space.

This pattern represents one particularly elegant solution to the basic relations of movement, access and privacy in urban residential neighborhoods. At a range of densities from single-family streetcar suburbs to walkup tenements and beyond, the same basic parameters apply.

The San Francisco pattern

While the 19th century rowhouse neighborhood — the “classic” model described above — is not the only solution that successfully integrates residential buildings and livable streets, it does offer a good illustration of the challenges involved.

The historic residential fabric of San Francisco often evokes a similar reverence, particularly in light of this city’s traumatic history in the 1950s and ’60s. But in spite of the extraordinary residential architecture here, a close look at the residential streets and buildings reveals a pattern with serious shortcomings for the public realm. And while there is no single physical pattern in any city, there are conditions that recur across districts and time periods, and come to typify something about the city’s identity.

Although the classic rowhouse model does exist in fragments here, it is by far the exception to the predominant pattern. San Francisco’s typical treatment of the two key transitions from roadway to sidewalk, and from sidewalk to building result in an erosion of pedestrian space and a weakened public realm.

Much of San Francisco was built or rebuilt after the advent of the private car in the early 20th century. Even many older Victorian houses have been retrofitted with a garage, and a great many residential buildings feature a separate driveway for each unit. The result is not only the too-familiar “garagescape” — a dead, blank streetwall — but also, somewhat less obviously, sidewalks that are diced up by an inordinate number of curb cuts and driveways.

Not only do driveways require that pedestrian space be shared with vehicles, but they also eliminate three distinct buffers provided by an intact city sidewalk: on-street parking, the curb itself, and curb-zone trees and streetscape amenities. When intact, these curb-zone amenities, foreshortened by a pedestrian’s oblique view, often merge into a continuous visual edge, defining the sidewalk as a distinct pedestrian space. In the gaps created by curb cuts, this buffer falls away, exposing pedestrians to the roadway and diluting the sidewalk’s spatial and psychological coherence.

These gaps often are much wider than the driveways themselves, because (to the familiar dismay of city drivers) the spaces between driveways often are too short for a parked car. Utility lines also are likely to be placed between driveways, precluding trees. In the end, fully half of a San Francisco sidewalk can be exposed to traffic, and what streetscape survives is characteristically gap-toothed and erratic.

Curb cuts erode the quality of pedestrian space, reduce the city’s tree canopy and (of all ironies) reduce the short supply of public parking, all in the service of a private easement. These ills are multiplied across the city, and because they are built into the city’s physical pattern, they stubbornly resist improvement.

The Building Edge and the Pedestrian Viewpoint

San Francisco’s typical residential pattern, notwithstanding its architectural charms, falls short of resolving the transition between the pedestrian and building zones. One of the most distinctive features of this city’s residential architecture is that buildings tend to built right to the property line and articulated inward from the building plane rather than outward from a setback line. While this may seem like splitting hairs, it has a major impact on both public and private space.

Consider the visual perspective of the pedestrian. Although buildings are usually drawn and photographed in elevation view, or from a direct frontal perspective — from across the street, say — pedestrians tend to see them obliquely, looking along the façade from the adjacent sidewalk. The setback zone in the classic rowhouse pattern, viewed obliquely, presents a complex but legible space, rhythmically articulated by usable stoops, with entrances easily visible. The San Francisco pattern, viewed obliquely, is all but featureless.It presents no visual articulation, no social space, and the entrances are hidden until you are nearly abreast of them. Even in fairly safe surroundings, an environment that resists being taken in at a glance and reveals a series of surprise recesses is not going to put people at ease.

The "Innie" Stoop

Another peculiarity of inward building articulation is the “innie” stoop, in which some or all of the entry stair is drawn deep into the building. This has the opposite effect of a traditional “outie” stoop’s privacy gradient, drawing the semi-public access functions into the private building’s interior. These cave-like semi-public interior spaces are socially useless — and present security problems for both residents, whose doors are invisible from the street, and passersby, who lose the natural surveillance provided by a sociable frontage. They are community black holes.

Instead of deftly managing the transition from public to private space, this form exacerbates the inherent challenges. Many building owners have recognized the security limitations of these kinds of stoops, and have “hardened” them with metal cages — an ugly and irrefutable sign that they simply don’t work.

The exception to this effect is the occasional much wider “innie” stoop, in which the front doors are arranged side-by-side, greatly enhancing visibility.

The lack of transition from pedestrian to private space in San Francisco’s typical residential pattern is exaggerated by one of this city’s architectural signatures: the bay windows that protrude into the public right-of-way from upper stories. By drawing the building plane into the street, bays further the impression of public space hard up against private residences.

It is important to note that this kind of buffer is important only in residential districts. Buildings at the property line and overhanging bays work beautifully on retail streets, where store windows make for transparent edges and visual penetration of the ground floor (that is, window shopping) is not only acceptable but essential. The same is true in high-density residential districts, where residential lobbies and other services provide a semi-public transition space.

In light of the pattern described above, what’s surprising is not the shortcomings of the city’s public realm, but its robustness and beauty. On many streets, a mix of delightful residential architecture, community stewardship and public investment have combined to create streets as beautiful and humane as any in the world. The segment of Noe Street between Market and Duboce, for example, was reconfigured in the 1970s to privilege pedestrians, with 90-degree parking, extensive plantings, and social spaces built into the design. Dolores Street’s dramatic palm-lined median, broad sidewalks and extraordinary tree canopy create a grand and comfortable setting for pedestrians, despite heavy traffic. Both of these streets include curb cuts, but they are few enough that they can be subordinated to pedestrian space. On both streets, community greening underscores and amplifies the public streetscape. The public potential of residential streets is revealed in many other places, where older buildings somehow avoided garage retrofits, where neighborhood gardeners have lavished their magic or where the stars have aligned to allow concerted public streetscape investment. But these are the exceptions, bucking a fundamental pattern that is physically predisposed against sociability and public life.

Looking Back, Moving Forward

The thoughtless and precipitous upheavals of mid-century urban renewal have made San Franciscans especially protective of the past. But the historic patterns of this city’s residential neighborhoods don’t offer especially good models for livable streets. And to a surprising extent, these patterns continue to be replicated in new construction as designers, developers and policymakers look to the city’s older neighborhoods as points of reference. Even as architectural styles, building codes, parking requirements and other parameters evolve, the urban fundamentals have remained surprisingly unchanged. It’s as if this pattern is woven into the city’s DNA, as if we are a city congenitally predisposed against good streets.

New districts such as Mission Bay and Rincon Hill, and housing reconstruction projects like Valencia Gardens present major opportunities to re-imagine the relationship between building and street, and they are making some progress. Among other things, larger projects (while problematic in some ways) can consolidate parking at the block’s interior, minimizing disruptions of the streetscape. But despite well-intentioned requirements for street access to ground-floor units, new residential development in San Francisco still generally builds to the lot line, creating small, awkward entry spaces that are impossible to occupy and, from the standpoint of the public realm, only marginally better than a blank wall.

There are terrific models — old and new — for this relationship, and not just in the Northeast. Emeryville, Portland, and Vancouver all boast at least some excellent new housing that both supports and benefits from the adjacent streets. There has been a great deal of discussion in San Francisco about the “Vancouver Model” for high-density housing — slender towers over a podium lined with townhouse units — but thus far it has consisted largely of anxious hand-wringing over tower heights and architectural style rather than close study of the details that make such projects work at the human scale.

A city designed for walking is designed for health, sustainability and democracy. In great cities, people who could do otherwise choose to be abroad on foot, among their neighbors, and become stewards of and advocates for public goods like parks, transit and public safety.

“Streets,” Walter Benjamin wrote, “are the dwelling paces of the collective.” And while good streets alone don’t make good cities, bad streets surely preclude the full expression of public life.