Seattle’s Olympic Sculpture Park turns an old tank farm into a place to relax, to think and to reflect on the city’s shared civic values — much like some sculpture gardens in San Francisco.

Despite the whiff of controversy that so often seems to cling to public art initiatives, most people continue to have a surprising amount of faith in art’s ability to ameliorate a host of urban ills. Art can soften the harsh edges of otherwise dauntingly angular monuments to corporate ambition (hence downtown art-enrichment ordinances that require developers to dedicate 1 percent or more for art to adorn the public spaces in and around their skyscrapers). Art can help to reclaim wasted or abandoned industrial spaces for new recreational and cultural uses. Art can reassert the presence of a beleaguered community in need of visual proof of pride and a celebratory sense of itself. Art can manifest core civic values — a commitment to environmental sustainability, to children and families, to cultural diversity. Art can provide a temporary, whimsical respite from the hard realities (or numbing routines) of urban life. And more.

Bike path through Olympic Sculpture Park. One of Louise Bourgeois’ Eye Benches can be seen on the left.

Seattle's Olympic Sculpture Park would seem to be exemplary of a number of these ambitions for art in public places. Sited on an old Unocal tank farm, the park repurposes a former brownfield, its nine acres cleansed of toxic waste at oil company expense, and purchased in a partnership between the Seattle Art Museum and the Trust for Public Land. While Olympic Sculpture Park offers a variety of visitor amenities — bike and pedestrian paths, waterfront access (including access to sandy Myrtle Beach), green spaces for lingering, thoughtful landscaping that highlights the native plant communities, a café — itsmain purpose is to showcase ambitious works of contemporary art. Some, like Mark Dion's Neukom Vivarium or Teresita Fernández’s Seattle Cloud Cover, have been specially commissioned for the site. Others, like Tony Smith's Stinger, Anthony Caro’s Riviera, and Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Typewriter Eraser Scale X were purchased and “plopped,” albeit with some sensitivity, at key places throughout the park. (An illustrated guide to the park can be downloaded here.)

Myrtle Beach, where families can stop to make their own temporary sculptures out of driftwood, perhaps inspired by Mark di Suvero or Alexander Calder.

A detail of Roy McMakin’s Love & Loss, with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Globe spinning in the distance. McMakin’s neon ampersand also revolves.

Roxy Paine’s Split, a trompe-l’oeil tree made out of stainless steel. Similar works were installed in New York’s Central Park several years ago as part of a very successful temporary public art initiative by Creative Time.

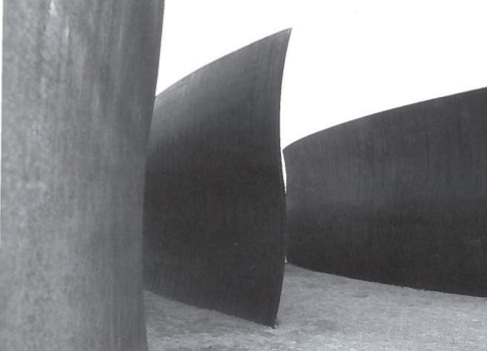

The best of these artworks respond particularly to the site in stunning and surprising ways. One of the great art experiences of the park (and Seattle in general) is provided by a complex arrangement of rusting curved-steel walls by Richard Serra, their materials reminiscent of the former industrial usesof the site, their forms recalling the prows of hulking ships. To see Wake from afar is to appreciate Serra’s almost magical ability to dematerialize steel into nearly weightless, abstract patterns. To come closer is to wander in a mysteriously quiet maze whose illusion of limitlessness makes the installation seem even bigger than it really is. In a completely different gesture toward context, Roy McMakin’s Love & Loss uses a painted tree trunk, a neon sign and cast concrete benches to set up a series of verbal and visual puns about this greatest dilemma of human relationships. Its graphic and pop sensibilities set up a clever dialogue with the landmark Seattle Post-lntelligencer animated sign that spins in counterpoint beyond the park's boundaries.

Tony Smith's Stinger, whose “dark star" form is counterbalanced by Seattle's futuristic Space Needle. New condo developments rise in the distance — another vision of Seattle's future.

A close-up of Richard Serra's Wake.

Olympic Sculpture Park was a very popular stop on the SPUR study tour. And since I am a member of the San Francisco Arts Commission, more than one person came up to me and asked the inevitable question: Why can't San Francisco have something comparable? The answer is, well, to some degree, it already does. The M.H. de Young Museum's Barbro Osher Sculpture Garden, freely accessible during the museum's open hours, is a more compact version of the same set of ambitions — to combine sculpture with landscaped, open space, to mix figurative and abstract, idea-based and form-based art, and to emphasize the contemporary (even though no one asks the question: What happens when a James Turrell environmental installation is as much an art “dinosaur" as Douglas Tilden’s 19th century bronze Mechanics’ Monument at Market and Battery Streets? The rooftop sculpture garden at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art willsoon be another such place. Yerba Buena Garden's art collection is slightly less obviously sculpturalin a conventional sense (it is more conceptual,in the case of John Roloff's Deep Gradient, and more commemorative, in the case of the fountain and waterfall memorial to Martin Luther King by Houston Conwill, Estella Majoza and Joseph DePace), but no less beautifully urban in its sensibility.And we certainly have room to do more — one site of opportunity might be along our increasingly lively central waterfront. The extensive and somewhat amenity-deprived shores of Lake Merced might be another.

But to make these other places into something like an Olympic Sculpture Park would take getting really clear on just what can and can't be done in the various public and private contexts in which art is commissioned and displayed. And so a better question might be, can the City alone be expected to provide the kind of art experiences that Olympic Sculpture Park provides? And the answer is probably no (Seattle no doubt recognized this). Olympic Sculpture Park was not the product of a community-based planning and selection process, which are the benchmarks of city-sponsored initiatives, art or otherwise. In Olympic Sculpture Park, art is allowed to be art, and not hijacked by some city department's desire for improved fencing or a bike racks paid for out of some other project budget than its own. Art is also expected to appeal to both local and non-local constituencies, chosen for the delight of both regular park visitors who have the opportunity to discover the pleasures of a complex work of art over time, and the visitor or tourist who may be inclined to connect the dots between their knowledge and experienceof art where they came from and what they see before them in Seattle. And in this sense, Olympic Sculpture Park has been clearly designated asa place for cosmopolitan urban encounters, an urban crossroads if you will, and not a place to permanently leave only locally interesting art tchotchkes like painted hearts, cows or globes left over from fundraising or public-awareness campaigns. San Francisco does have places where its relation to an international community of artists and art lovers is spelled out, but its major public parks, plazas and open spaces are by and large not among those places and, for better or worse, depending on who you talk to, may never be.