One of the main things people like about older San Francisco buildings is the taller ceiling heights, both at the ground floor and the upper stories.

At the ground floor, ceiling heights are a critical part of what makes a retail space inviting and what makes a building feel comfortable for pedestrians on the sidewalk next to it. Many people have fond memories of old-fashioned retail establishments with high ceilings and generous natural light here in San Francisco. Typically, the older ground-floor retail spaces were a story and a half tall. And indeed, many of these places still exist and contribute to our beloved older neighborhood commercial streets.

Low ceilings make uninviting spaces that rent for less, feel cramped, are less visible from the street, and don’t allow commercial uses to easily flourish. For just these reasons, in new suburban malls and shopping centers, retailers consider ceiling heights of 16 to 24 feet essential to the success of the stores. And that is exactly what they build. Of course, taller ceiling heights are also required for light industrial uses to be located on the ground floor of a building.

Tall ceiling heights are just as important on the upper floors of a residential building. Pre-World War II apartments in San Francisco have a well-deserved reputation for feeling spacious and being filled with light. High ceilings are the design element most often mentioned when people talk about what is special about San Francisco’s historic apartments. These rooms often have ceilings as high as twelve feet, compared with standard ceiling heights on new construction today of eight feet. Instead of “gracious,” an adjective we hear more often describing these spaces is “mean.”

The squashed ceiling heights, found at both ground floors and upper floors of newer buildings, make it very hard to achieve the feelings of space and grace appreciated so much in traditional buildings. Whether people are consciously aware of this fact or not, it has a profound impact on the comfort one feels in them.

These issues don’t come up in the suburbs, where all buildings are more or less single story and where working, shopping, and living are separated into “zones” that people drive between. In a city, where activities are mixed vertically in the same building, it is critical to livability that multistory buildings be designed to feel comfortable. Why can’t we design new buildings with the higher floor-to-ceiling heights that we find on most older buildings? Both the answer and the solution lie in the relationship between the Planning Code and the Building Code.

Government codes affect built form in unintended, and sometimes negative, ways

The design of new buildings in San Francisco is influenced by two sets of overlapping rules: first, the local San Francisco Planning Code, written and administered by the San Francisco Planning Department; and second, the national Uniform Building Code (UBC), administered by the San Francisco Building Department but written by the International Congress of Building Officials. Not surprisingly, these two codes have been written in isolation from each other. The interaction between these codes unintentionally pushes buildings into a format of low ceiling heights at both the ground floor and upper floors, even when this is not desired by neighbors, city planners, developers, architects, or the future residents of the building.

Presented here are case studies analyzing the effects of 40-foot, 50-foot, and 65-foot Planning Code height limits on urban form, given the Building Code strictures which also must be met. In each case, the question is asked, what simple adjustments can be made to the Planning Code to achieve the “highest and best” interior building spaces and exterior pedestrian realm? This article proposes aligning the requirements of the Planning Code with those of the Building Code in order to increase the quality of the environment both within new buildings and in the public realm around them.

Such a change would require no change in the Building Code but would instead calibrate the Planning Code to the Building Code.

Recommendations

All the great cities of the world achieve walkable, vital street life and convenience in daily life by mixing different uses in the same building. The vast majority of the new development that takes place in San Francisco is going to have multiple stories. To make that development comfortable from the street, we would do best to build extra-tall ground floor spaces, whether they are for shopping or for doing other work. And to make the upper stories gracious and comfortable, we would do best building taller ceiling heights as well.

In order to do this, the Planning Code needs to regulate not just the total height of the buildings, but the allowable number of floors as well, either by requiring minimum ceiling heights that are taller than the Building Code currently requires or simply setting a maximum number of floors that can be built within a given building height.

If we reduce the number of floors that can be built within each of the current height districts, one side effect would be the reduction of the total density of new buildings—thereby restricting housing supply and forcing development “somewhere else,” meaning the periphery of the region. The better answer is to slightly bump up the height limits, while allowing the same number of stories we allow today. If nothing else, it is in the public interest to set a minimum ceiling height on the ground level, which has the most direct impact on the quality of the public realm, as experienced by pedestrians.

Case Study One: 40-Foot Existing Zoning

- Retail street in multi-family use zones (does not apply to RH-1 or RH-2 residential districts)

- Typical uses: 3-story residential apartments or condos over ground floor retail

- Construction Type: 4 stories of wood frame

- Most residential neighborhoods in San Francisco are zoned in the Planning Code for a 40-foot height limit. This discussion does not apply to single or two-family residential districts, but to those retail streets that are zoned for multi-family residential yet still have a 40-foot height limit.

- The minimum allowable floor-to-ceiling height in the Building Code is generally 8 feet, to which floor thicknesses of one to two feet must be added. In such districts, it is possible to construct a maximum of4 stories. Assuming 3 upper stories with the minimum ceiling heights, and some additional cornice or parapet at the roof level, there is enough height within the zoning limit for a ground floor with approximately a 9-foot high ceiling.

- If the Planning Code were changed so that these 40-foot height limit zones became instead 45-foot height-limit zones, and the number of stories were restricted in the Planning Code to 4, this could result in a 14-foot high ground floor— what many of our nice old buildings have—although still with low 8-foot high ceilings in the upper stories. These upper stories would still feel too cramped to be gracious, but at least the part of the building that touches the sidewalk would feel comfortable, and tend to attract the wonderful service uses—neighborhood shops and restaurants and cafes—we want to patronize. Alternatively, some forms of light manufacturing can be accommodated in a ground floor of 14 feet that simply is not possible in a 9-foot ceiling height.

- Few neighbors in multifamily districts would be able to recognize the difference between 40 feet and 45 feet, and in fact, older buildings already exceed 40 feet in many cases. But the difference in the quality of space both within the building and in the public realm outside the building is dramatic. Instead of concentrating on this “magical” 40-foot limit, the public interest would be better served by increasing this height a modest 5 feet to create the conditions that would result in better ground-floor spaces.

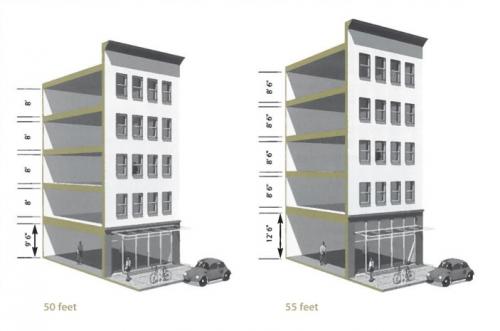

Case Study Two: 50-Foot Existing Zoning

- Uses: 4 story residential over ground floor retail

- Construction Type: 4 stories of wood frame over concrete slab between the ground floor and upper floors

- In some slightly denser neighborhoods, parts of the Mission District, and along some retail streets such as Geary in parts of the Western Addition, as well as some other areas, height limits are 50 feet. With four stories of 8-foot ceiling heights on the upper levels, a 50-foot tall building can now have a 10-foot high ceiling height on the ground floor and still remain within the 50-foot limit. However, for buildings over 50 feet in height, the Building Code requires the structure between the ground floor and the upper floors to be concrete. Raising the overall height modestly—as in the previous 40-foot example—is more difficult because adding height under the Planning Code means that under the Building Code a whole different, more-expensive construction type is required (such as light-steel construction for the entire building). The solution is to either revert to 4 stories in 45 feet (see previous example, p. 9) or up-zone to 5 stories in 55 feet, acknowledging that the construction costs will be higher. If the former alternative is chosen, the developer and the city lose the benefit of an extra story of desperately needed housing. If the latter alternative is chosen, the developer (and ultimately the resident of the housing), pays a small premium for a more expensive but superior construction method.

Case Study Three: 65-Foot Existing Zoning

- Uses: 5 story residential over ground floor retail

- Construction Type: 6 stories of concrete or light steel, or 5 stories of “special wood framing” over one story of concrete

- Some older areas of the city, such as the Tenderloin and parts of Polk Gulch, as well as others, are zoned at a 65-foot height limit. A 65-foot height limit allows an additional floor of residential and a greater ground-level height than does the 50-foot height limit. The lower level can then become a generous height for retail or light industrial uses. In addition, since the ceiling structure of that floor is concrete, it provides excellent sound and fire safety isolation for residences above. A 65-foot height limit allows both the apartment ceiling heights in the upper stories to be greater than the minimum and also have graciously scaled retail below. Note that the Tenderloin is precisely one of those older neighborhoods that has both active street level activity and gracious apartments above, the combination of which have earned the Tenderloin the sobriquet “our Parisian district.”

- This is a case where the Planning Code height limit allows a high ground floor without losing an upper story.