"This way to your Dream 'House'." The billboard's arrow is a little green "Monopoly" cottage that points invitingly skyward, a perfectly condensed signifier of the ultimate urban desires for privacy, prestige, penthouse-quality panoramas and a piece of the action. Among the first things that strike you as you wander Vancouver's waterfront are the number of brightly colored real estate billboards and the number of really tall construction cranes. Construction-site clutter is sometimes hard to overlook, but this is what real estate advertising does so well. It visualizes our dreams fulfilled--"unrivaled waterfront residences," "spectacular lofts," views that "start where others leave off," a perfectly urbane equilibrium of "comfort" inside and "nature" outside.

And the pitch doesn't stop there. On our first day in Vancouver, participants in the SPUR study tour gather at the Concord Pacific Presentation Centre, where another of the megaprojects for which Vancouver is becoming increasingly renowned in planning and development circles is taking shape nearby. We are ushered into a nicely upholstered circular projection room and the lights dim. As music pulses and a parade of youthful and ethnically diverse faces appear onscreen, we are given the seductive (hard) sell: if we buy one of the townhouses, lofts, or condos at Concord Pacific, the video clips assure us, we will find ourselves not merely housed but "HERE." Privileged inhabitants of a special urban place, we will dine impeccably and healthfully every day, we will dance with abandon at hot new clubs every night, we will stroll through verdant parkways to great shopping and personally fulfilling jobs, we will exercise religiously but painlessly, droplets of water sliding in ever more impossibly decorative patterns over our taut bodies as we slice through the pristine water of the pool at the in-house spa facilities. We squirm uneasily in our seats. We want to talk number of units and floor-area ratios. We feel much better when the city's Co-Director of Planning Larry Beasley strolls in wearing an understated dark suit and begins to speak earnestly and articulately about the everyday practicalities of long-range planning. But this moment of apparent cognitive dissonance is also a moment when I become even more interested in what a recently published book proclaims as "The Vancouver Achievement."1

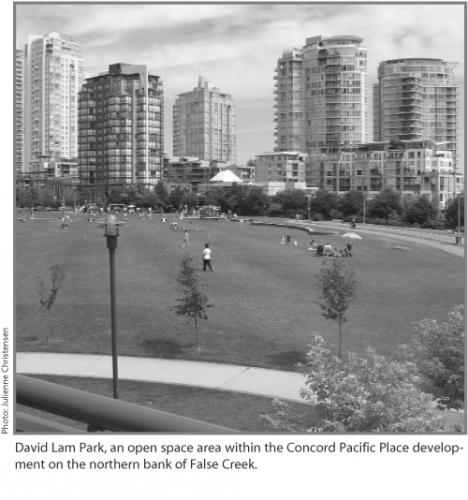

Why did SPUR go to Vancouver? To be sure, our goal was strategic rather than encyclopedic. We didn't go to look at economic development schemes. We didn't go to look at transit. We didn't go to look at social justice issues, or how Vancouver cares for and copes with its homeless population. We did go to look at one specific model for high-density, high-rise urban development, and at the interface between high-density housing and an enhanced public realm--waterfront parks, bikeways, and pedestrian paths, community centers, and that promised land of contemporary city planning, "real" neighborhoods.

As for me, my mission was perhaps even more limited. An advocate for community-based planning, I am also a veteran of protracted neighborhood planning battles that have been anything but examples of good public process. An attentive student of comprehensive planning in San Francisco, I also have to admit that an alarming number of these initiatives seem unable to move from theory to praxis. Intensely aware of my own contradictions, I wanted to see for myself how Vancouver got anything done at all, planningwise.

This is why on the second day of the trip, when presented with a choice to spend the afternoon touring Yaletown, one of the newer urban-infill areas, or attending a community planning forum, with regret but noble firmness of purpose I passed on the considerable pleasures of Gordon Price's skills as an urban interlocutor and grabbed a cab for the False Creek Community Center, where a plan for a new residential community in Southeast False Creek was slated to finish up the first round of "public consultation."

In many ways, the Southeast False Creek project represents the next generation of megaplanning in Vancouver. Several years in the making, it adds social, economic, and ecological-sustainability requirements into the mix of goals for housing production, waterfront greening, and neighborhood building that have characterized developments at Coal Harbour and Concord Pacific. Over 80 acres of former industrial land are slated for new development, with 30 acres privately held. The aim is to create 2,000-2,500 units of housing on public lands, with family housing a priority, and zone for the possibility of another 3,000-4,000 units of housing on private lands, with live-work space a priority.

The public realm of Southeast False Creek is envisioned as a network of open space and parks, streets and pathways to connect all portions of the community, and pedestrian, bicycle and transit links to adjoining neighborhoods. When completed, the development area will include high-rise, medium-rise, and low-rise buildings, and amenities such as community centers, childcare facilities and gardens. "Heritage" (historically important) industrial buildings will be preserved, and new commercial-industrial space will keep people working in their neighborhoods. The buildings are to be designed to be healthy and efficient in their uses of construction materials, energy, and water. The water's edge will be designed to increase the biodiversity and ecological health of the restored wetlands habitat. Demonstration projects in advanced technologies for renewable energy, water management, green building, and urban agriculture will be encouraged where feasible.

All of this is no small beer. It also can't be without controversy, I think to myself as I approach the community center (more tall buildings! more people! gentrification!). Surely here, if anywhere, I'll catch a glimpse of that debilitating confrontation of competing special interests that has come to characterize the public process component of city planning--even in Vancouver.

Once inside the center, I am greeted by planning staff and invited to help myself from trays of deli sandwiches and vegi burritos. The room is ringed by easels displaying proposals for housing densities, green spaces, transit routes, and more, and summaries of the public comments received thus far. A generously scaled table-top model of the proposed development area is set up in back. About a hundred or so people mill about, perusing the illustrated boards, nibbling from plates of food, and talking to one another. The majority of people are white, and somewhere between 30 and 50 years of age, but there are some families with children and babies, some senior citizens, and a scattering of Asian faces across the generations. Perhaps even more significant than the demographics of the crowd is its temperament. Nobody seems angry.

As the meeting opens, a senior planner welcomes the crowd, brings them up to speed on the progress of the plan thus far, and sets expectations. Today is the last opportunity for public comment before the plan, he tells them. In the following months, the plan will be revised as a result of this public process and submitted for final review in early fall. The consulting architect is up next. He begins to step through the overall concept for the project, but to my surprise he doesn't begin where I expected. The guiding vision for Southeast False Creek is apparently not to zone for buildings up to 275 feet tall where nothing half so high currently exists (although the plan does that). The guiding vision also seems not to produce two million square feet of residential space and two hundred thousand square feet of commercial space (although it does that too). The guiding vision, the architect announces cheerfully, is to create livability, and more than that, to aim for "the best living a city can offer--the accomplishment of delight, comfort, and joy." Delight, comfort, and joy" I look up from my notebook and think back to Concord Pacific. Something clicks.

Other contributors to this newsletter will, I imagine, also emphasize some of the main points that seem to make planning work better in Vancouver than it currently does here in San Francisco, among them the priority given to completing comprehensive planning initiatives, the public confidence resulting from past successes, and the de-politicization of project planning. These are all important factors. And don't get me wrong. The Southeast False Creek meeting was not without its glitches. At the opening of public comment, a rather wild-eyed gentleman charged to the front of the room and made an impassioned and profanity-laced speech about the stupidity of city planners in general and these planners in particular. I traded gleeful glances with some other SPUR study tour participants in the room. To be honest, we were a bit glad to see him. Things were a little too perfect. But I also have to admit that he was the exception rather than the rule, and not only at the community meeting, but among the dozens of people I stopped on the street as we toured the city, to ask them how they felt about "big development" in Vancouver. The fact is, at least according to my unscientific survey, they feel just fine. Things are "better," they say.

So here is what I learned from Vancouver: we desperately need to start planning for delight. The Better Neighborhoods initiatives2 here in San Francisco are a good start, but we need to go further in order to radically change our dysfunctional planning culture.

Planning for delight means taking the attractive, desirable, and beneficial potential deliverables of city planning seriously and leading with them whenever possible. Asking people to help make their neighborhoods nicer is a powerful incentive to positive participation.

Planning for delight also means embracing forbidden words. A striking feature of public planning discussions in Vancouver is that people are allowed to talk about the urban amenities that are important to them without entrenching them in euphemisms that only impede the process and further muddy the waters. The vexed question of views is a good example of the paradox entailed by attempting to repress such discussions. If people are anxious about views, why mire them in hair-splitting debates about "privacy, light, and air"--even as the developments they are often concerned about will put billboards on every new rooftop, promising their own constituents "breathtaking panoramas" of bay, bridge, and city skyline?

The problem might be put this way. The real estate business has always promised more than it can deliver, and these promises are so obviously qualitative that it almost seems to go without saying. But planning has a history, it seems to me, of often aspiring to less than its potential, or at least casting its potential largely in hygienic, disciplinary, and quantitative terms. Ironically enough, in planning discussions it's more often than not the old "bad" city that gets to be qualitative. The bad city is not only dirty, dangerous, and dysfunctional; it is also anecdotal and full of unplanned incident--which is why people tend to be nostalgic about it despite its drawbacks. Planning responds with abstractions--discussions of housing "units" rather than homes, of complicated zoning formulas rather than concrete examples of land use. And if you lead with these discussions, you shouldn't be surprised to find people coming up with some formulas of their own.

In the end, my argument is not that planning should become more like real estate advertising, filled with overblown promises of physical perfection, true love, and matching linens, but that its strengths should be understood to lie primarily in its abilities to facilitate a productive relationship between public good and private enrichment. Of course good planning will not help your hair grow back or ensure that you get lots of dates. The delights it is capable of providing are more tempered and prosaic--generous sidewalks, well-placed neighborhood-serving retail, attractive and safe streets, a small park or a group of benches just when you need to sit down for a minute, a public view corridor that asks you to pause and admire the city as you round the corner, a respect for the unique quirks of a place that sometimes just need to be left alone. But rather than being exclusive and segregated, these delights are also broadly and democratically shared (this has always been the case, even in disciplinary cities like Haussmannized Paris, where such hygienic programs as ridding the water supply of cholera helped everyone--even though there were some civic leaders who might have wished them selectively applied, leaving the poorer and more politically volatile areas of town to have their populations periodically winnowed by cleansing epidemics). City planning is so powerful to me for this reason--not because it can force people to live differently, but because it can make good things available to more people. People need to be reminded of these benefits at the outset of every discussion--and shown how they can accrue as a result of well-planned development.

As the community meeting continues, I half listen to audience suggestions to find more ways to involve people creatively in the interaction between land and water, to include teaching gardens and farmers markets in the urban agriculture program, to make sure there are enough playing fields for sports, to integrate the "social housing" throughout the site, and more. By the time I am writing this essay, the public comments have been summarized and posted on the Southeast False Creek website3--the revised plan should appear there shortly and given Vancouver's track record, will probably move forward as expected. Meanwhile here in San Francisco, such planning basics as the Housing Element of the General Plan and such cart-before-the-horse maneuvers as the Rincon Hill projects (that seem destined to precede the Rincon Hill Rezoning plan4) grind their way through an increasingly contentious review process. But if opposition to these initiatives continues to mount as people perceive the one solely in terms of parking and livability takeaways and the other in terms of merely tall buildings, then perhaps we have to ask ourselves: have we given them anything else to think about?

Jeannene Przyblyski is a SPUR board member, professor of art history at San Francisco Art Institute, a Friends of Noe Valley board member, and executive director of the San Francisco Bureau of Urban Secrets, a visual arts and urbanism think tank.

Endnotes

1 John Punter, The Vancouver Achievement: Urban Planning and Design (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2003)

2 For more information on the Planning Department's Better Neighborhoods program, see http://www.ci.sf.ca.us/planning/neighborhoodplans/

3 Southeast False Creek Policy Statement, www.city.vancouver.bc.ca/commsvcs/currentplanning/sefc/intro_page.htm

4 For more information on the Planning Department's Rincon Hill Rezoning plan, see http://www.ci.sf.ca.us/planning/citywide/rinconhill.htm