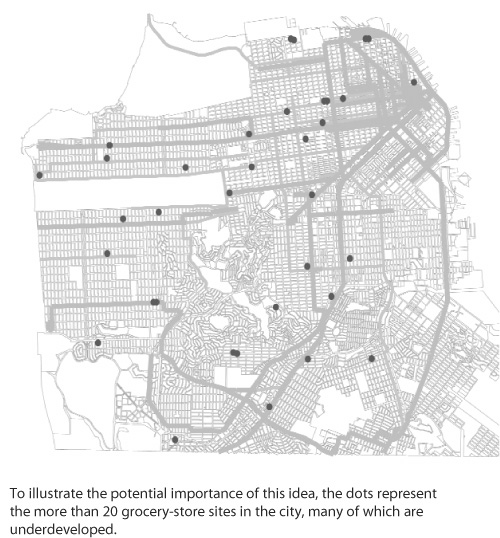

Grocery Store Sites

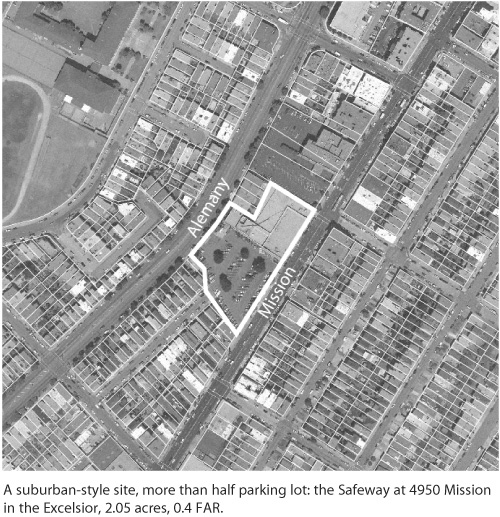

Grocery stores are typically sited along established neighborhood commercial corridors that anchor residential districts. They are often along or within easy walking distance of the city’s core transit streets. These sites commonly have large one-story commercial spaces ranging from 25,00–80,000 square feet located at the interior of lots that average 1.4 acres in size. Surface parking typically occupies the majority of the site and all major frontages. In terms of buildout potential, these sites rarely use more than one-fifth of the permitted floor-area-ratio (average .57 floor area ratio of 2.5 permitted), and rarely include housing.

Shopping Mall Sites

Shopping mall sites are larger and fewer. Surprisingly, they too are typically along the city’s core transit streets. They vary in size and overall density of development; in all cases, they represent large breaks in the urban fabric of surrounding neighborhoods creating street-less superblocks of large internally-oriented complexes.

What Can Be Done?

Seattle, Portland, and Vancouver have each seen a wave of new and rehabbed grocery stores developed in more urban mixed-use models. All of these cities have planning code controls that encourage and sometimes require a mixture of housing with commercial development. Fortunately, almost all of the mixed-use grocery store projects to date in Portland and Seattle have materialized due to strong initiative from the development community (one Seattle planner described a development company that “got religion”) and, on occasion, to redevelopment coordination by the cities themselves.

While here in San Francisco there is a demonstrated capability and interest from the development community in mixed-use grocery store development (the new Fulton Market and the Alemany Albertson’s are two examples of recent strides toward this model), many other grocery and large retail sites in areas appropriate for housing continue to be proposed with minimal reinvestment and the perpetuation of single-use commercial buildings set in surface parking lots. It seems that high land values are not enough to spur supermarket operators to seek a development partnership that includes housinglselect zoning and planning code revisions are likely needed to encourage this form of reuse. These types of development arecertainly more complicated (especially regarding financing) than simple grocery stores, and grocery operators need to be encouraged into partnerships with developers experienced in mixed-use and housing projects.

Several zoning and planning code changes, along with urban design guidelines, would encourage the redevelopment of these sites with a substantial amount of new housing, more active retail frontages, and better urban design overall to make these sites fit with their more fine-grained neighborhood contexts:

Housing as a Required Use: Ratios, Thresholds, and Minimum Densities. There is already a precedent in San Francisco zoning to require housing in certain districts where it is desirable and where the demand to build commercial space or other uses can be leveraged to introduce housing into the mix. For instance, the existing Van Ness Special Use District allows non-residential uses only if the ratio of residential to non-residential square footage is 3:1, and Rincon Hill zoning requires a minimum ratio of 6:1. Such a ratio could be incorporated into new zoning applied specifically to targeted large commercial parcels in question; a better option is to apply the ratio more broadly across Neighborhood Commercial districts to encourage mixed-use on all larger sites through the use of thresholds: development on parcels above a certain size (say, 1/2 acre) and/or of commercial development above a certain size (say, 10,000 square feet) would trigger the minimum housing ratio (such as 2:1 residential to non-residential square footage). Instead of a ratio, a minimum residential density (say, 50 units per acre) could be applied to any site or commercial development greater than a certain size. Portland, Oregon has used all of these, for example, instituting minimum floor-to-area ratios (FARs; the ratio of the buildable area to the total area) and minimum residential density requirements near light rail stops, and that city’s equivalent of Neighborhood Commercial zones have a 1:1 minimum residential to retail requirement for all parcels.

Relaxation of Parking Requirements. Parking requirements for commercial uses are based on a “destination retail” model (where everyone must drive), and not a neighborhood commercial model, where multiple shops line a walkable street. For large commercial uses in Neighborhood Commercial districts, parking requirements could be relaxed to encourage building forms that make a better “fit” with the neighborhood, and reflect neighborhood characteristics such as the density and mix of uses in the surrounding area, transit accessibility, and synergies with other commercial uses. In tandem with reduction in parking requirements and encouragement of a less car-based urban lifestyle, large commercial uses should engage in services such as home delivery, customer shuttles, and hosting car-sharing pods.

Design Standards for Street-Facing Uses. Controls are needed to ensure that street-facing uses contribute to the urban quality of neighborhood commercial streets. There are already many controls that address this for individual (narrow) frontages, but none that adequately address large uses and sites. Mitigation of parking impacts and scale are most pressing for these large uses, as they generally require moderate amounts of parking. Strategies might include requiring any above-grade parking to be set back at least 25’ from sidewalks and “wrapped” with active uses such as retail, community facilities, residential units, lobbies, and stoops/entries to individual residential units; restricting parking and loading entries and access to a base minimum width (20' and 22', respectively) and located on side streets only. Individual retail frontages should be limited in width to encourage large retail spaces to be lined with smaller retail spaces facing the street. Primary functioning entries to the main grocery stores and auxiliary retail spaces should be directly from sidewalks, rather than parking lots.

Design Standards for Large Parcels. Because of their sheer scale, often surrounded on all sides by fine-grained neighborhoods, large sites and sites with large uses need extra design sensitivity to fit in with the neighborhood fabric. Critical neighborhood pattern elements that might counteract the tendency toward building agglomeration and out-of-scale gigantism include the introduction of new streets and alleys to break up large sites into pedestrian-friendly blocks, the construction of multiple discrete buildings on a site instead of singular large masses, and incorporation of public plazas or open space. Some of these sites might require deliberate community-based planning and outreach efforts to incorporate community desires and needs, such as, for open space and community facilities.

Public Amenity/Value Recapture Programs. It will be important to ensure that some portion of the value created from new development comes back to the community. In addition to the vitality that new housing will provide, publicly-accessible open space, streetscape enhancements and other amenities might be either funded through or created as part of new development.

Substantial outreach and effort is needed to engage and inform developers and the public about the benefits of this kind of reuse, so that opportunities are not missed when redevelopment or retrofit of these sites are proposed and discussed.