Today I’d like to speak about the emergence of a new model for the urban park, the “ecological” park. When talking about parks, it’s important to begin at the beginning, with the idea of nature. The park developed out of a world view that sets nature and culture in opposition to each other. By nature I mean the primeval—predating things human. In the first century A.D., Cicero described the primeval as “first nature.” Set in opposition is the idea of culture—the landscape utilized by humans for their benefit. Cicero called this utilitarian landscape “second nature.”

In the 18th century, a middle ground between nature and culture emerged from this opposition—the picturesque or pastoral. This landscape referenced nature visually, but was the product of human hands. It emulated the rural landscape of the English countryside. John Dixon Hunt has called pastoral landscapes “third nature.”

The urban park is an expression of this pastoral idea. From their inception, urban parks were not conceived of as having ecological value or as being ecological restorations in the sense that we use these terms today. Fredrick Law Olmsted designed New York’s Central Park to provide the aesthetic experience of nature as an antidote to urban life, not to create ecological value. Central Park is not a relic wilderness surrounded by urban development. It was constructed at great effort and expense, involving the relocation of several communities, the movement of six million cubic yards of dirt and rock, and the planting of thousands of trees. Its construction transformed a rocky stretch of farmland in the middle of Manhattan that was not desirable for urban development.

It is ironic that picturesque parks like Central Park are associated with nature. By modern standards, most parks are not very ecological. Because parks are based on an English landscape model, they aren’t really suitable to many sites. As wonderful as Golden Gate Park is, it is fundamentally an attempt to replicate something that doesn’t really belong there. It survives at great expense, both ecological and financial. To create this pastoral effect, parks depend on non-native plant species that have a finite life span, and require high maintenance and frequent replanting. The dying planted forests of Golden Gate Park and the Presidio are good examples of this phenomenon. Urban parks often incorporate sweeping green lawns that require huge inputs of water, fertilizer, pesticides, fuel, and labor. Parks aren’t sustainable, self-replicating, or ecological landscapes, though they may look natural to our eyes.

Nevertheless, urban parks endure and are beloved. In The Politics of Park Design, Galen Cranz suggests that new park models evolve in response to changing social needs in a changing world. I think it’s safe to say that the world we live in today is very different from the mid-19th century world in which the picturesque park first evolved. Today, we live in a world where science and metaphysics suggest the earth is an integrated whole. We live in a world where we value nature by virtue of its ecological worth and not just its aesthetic appeal, where biodiversity, environmental justice, climate change, habitat protection, and sustainable economic development are both social and environmental needs. Today we think of the world as having limits and resources as finite.

I believe the ecological park is emerging in response to these changing social needs. I would like to share with you the five characteristics that I think distinguish ecological parks from more conventional, picturesque parks.

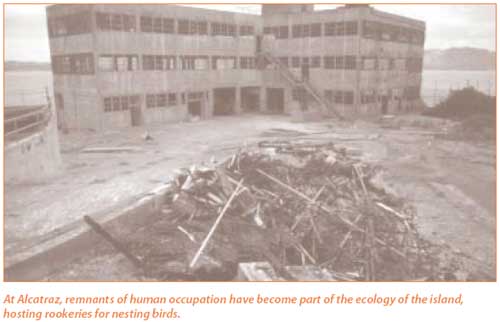

First, ecological parks reflect a holistic, integrated vision of the earth. Ecological parks derive from a world view that breaks down the dichotomy between nature and culture. This allows all of the landscape potentially to have ecological value. Alcatraz is an excellent example of this. Since the closure of the prison in 1963, much of Alcatraz has been re-colonized by bird life. And although more than a million visitors a year visit 11-acre Alcatraz, the island houses about 15 percent of the Bay Area’s western gulls, about 15 percent of its black crowned night herons, and a very large colony of pelagic (oceanic) birds. Many of the wildlife habitats are the accidental byproduct of human interventions in the landscape. The landscape of Alcatraz tells a fascinating story.

The western cliffs originally had a far more gradual slope. They were heightened to make the island fortress more impregnable. Today these constructed cliffs are used by hundreds of pelagic birds for nesting and roosting. Rubble dumped in the bay during the island’s development has turned into a unique in-bay tide pool complex. Formerly manicured, historic gardens have gone wild, creating habitat for a colony of egrets, black-crowned nightherons, and great blue herons. Since the island was opened to the public in 1972, public use and heron use have both expanded dramatically. The flat, concrete parade ground has been colonized by hundreds of nesting western gulls. The rubble piles surrounding the former parade ground have the highest species diversity of any part of the island. They are all that remain of the four-story apartment blocks that were demolished by the General Services Administration after the Native American occupation in 1969. That they’ve been re-colonized by wildlife bursts our preconceptions about where natural value resides.

Second, ecological parks are conceived as part of an integrated urban whole. As I previously mentioned, picturesque parks were conceived of as experientially isolated from the surrounding city. Because ecological parks are conceived as a part of an integrated urban whole, they can participate in solving larger urban and ecological problems.

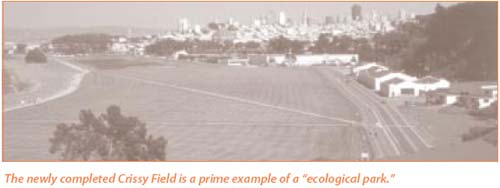

The reconstructed marsh at Crissy Field is a good example of this. Crissy’s 20-acre salt marsh was reconstructed in an area that was historically salt marsh. Two-thirds of the Presidio falls within the watershed of the Crissy marsh. Storm drains that used to dump storm water directly into the bay now flow into the marsh. The marsh “treats” this storm water by providing an opportunity for sediment and nutrients to fall out before the water reaches the bay.

The marsh also fills a gap in the Pacific Flyway. Previously, a bird flying along the coast would have to fly from the Mill Valley marsh to near SFO before it could find another significant marsh habitat along the bay. The restoration of Crissy creates a new habitat roughly midway between them, restoring an ecological process that is larger than the site. The marsh restoration also included re-establishment of a regionally limited habitat type, the back dune fen or dune swale, and the reintroduction of unique plant species.

Third, ecological parks use sustainable design, construction, and management practices to reduce resource inputs and waste outputs. The use of recycled materials can be a very small and simple gesture. In the National AIDS Memorial Grove, we used old granite curbstones removed during street modernization to create stairways and erosion control.

Sustainable building practices were central to the transformation of Crissy Field. Construction of the Crissy marsh involved the excavation of about 230,000 cubic yards of earth. Instead of dumping the spoils, we re-used the material on-site. The airfield was tipped up along its north edge so that it gradually rises to a height of eight feet above the promenade. This not only improved drainage on the formerly flat site, it absorbed a large quantity of the excavated material. The remaining material was used to create the west bluff picnic area and landforms near the east beach parking area.

Construction also involved the removal of 70 acres of asphalt and 15,000 tons of rubble from the beach. The rubble was re-used in the landforms and for bollards and other landscape features at the site. The asphalt was crushed on-site and used under pathways and parking lots, and as structural fill.

Crissy Field also takes a sustainable approach to the use of plants. Most parks use very high-maintenance plantings. At Crissy, all of the plants except the pre-existing trees and the entry grove are native to the Presidio. The turf grasses are all native species. We planted salt-tolerant, native rye grass and salt grass in the areas used by board sailors so that they could rinse off their boards and the salt wouldn’t affect the turf. Native red fescue and Pacific hair grass were planted on the airfield and landforms. Natives will better tolerate the harsh conditions at Crissy, and require less frequent mowing, less irrigation, and no pesticides.

In non-turf areas, only native fore dune and back dune species were planted to create a sustainable, selfregenerating landscape that will require only a couple of years of establishment irrigation, no pesticides, and moderate weeding until a dense plant cover is established. Once these species are established, they should continue to propagate themselves so that we’ll never have to replant.

Fourth, ecological parks no longer depend on picturesque aesthetics to communicate the idea of nature. Rather, they are part of an expanded field of landscape aesthetics. They are an example of what I call “fourth nature,” landscapes that express that they are made and yet have ecological value. This notion of fourth nature is important, because it allows us to conceive of ecological value in landscapes that we traditionally have thought of as cultural. It allows us to abandon our preconceptions about landscapes like formal French gardens and see the ecological richness they hide.

Alcatraz is an interesting example of fourth nature. It teaches us that formal elements like hedges and walls can sometimes be ecological devices. Because they allow human use to coexist with wildlife, some design “intrusions” are an integral part of the ecological story of many urban places. Crissy Field’s boardwalks and fences are generators of ecological value because they eliminate potential conflicts between visitors, wildlife and native vegetation.

By moving into a new aesthetic realm, ecological parks are beginning to generate new types of landscape expression. Ecological parks speak to what is unique about a site and a region, and do not just replicate a model inherited from Europe. The ecological park also suggests a new role for designers and for design. In picturesque parks, the idea was to create a picture and freeze it. In ecological parks, I believe the role of the designer is more about creating a frame within which social and natural processes are allowed to generate and maintain the form itself.

By moving into a new aesthetic realm, ecological parks are beginning to generate new types of landscape expression. Ecological parks speak to what is unique about a site and a region, and do not just replicate a model inherited from Europe. The ecological park also suggests a new role for designers and for design. In picturesque parks, the idea was to create a picture and freeze it. In ecological parks, I believe the role of the designer is more about creating a frame within which social and natural processes are allowed to generate and maintain the form itself.

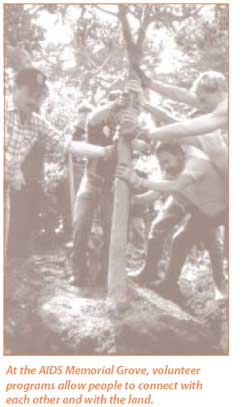

Lastly, ecological parks serve as a vehicle for reconnection. There is a nesting hierarchy of types of reconnection that parks can generate. Parks can provide an opportunity for passive contact with nature. Environmental education programs, waysides, and other types of environmental education generate a deeper understanding.

Programs like the Presidio Stewardship Program and the Crissy restoration effort engage thousands of local residents in the restoration and management of the landscape. Over 3,000 volunteers from the community collected seeds, propagated and planted over 100,000 native plants, and weeded as part of the Crissy restoration.

At their best, ecological parks can create a deep connection among people and between people the land itself. The National AIDS Memorial Grove in Golden Gate Park is an excellent example of this idea in action. The grove has been conceived of, created, funded, and maintained in a wonderful partnership between the city of San Francisco and thousands of individual citizens. Over the last eight years, thousands of volunteers have transformed a derelict section of Golden Gate Park into a wonderful habitat for people and wildlife.

What I find interesting is that visitors are prompted to leave a memento or to interact with the site in ways that are unusual for urban parks. Most of us go to parks, lay out a blanket and have a picnic, but we don’t touch the earth, plant a plant, leave a memento, or throw some seeds. Because of the role citizens have played in the creation of the grove, it has become a park landscape with profound meaning for thousands of people. The lesson of the grove is that parks can be so much more than they have been in the past. The old idea that parks are something outside of us—something that we experience primarily with our eyes—is obsolete. Ecological parks can become powerful vehicles for reconnecting us to the land and to each other, and for making our urban lives much more wonderful and beautiful experiences.