introduction and background

Many people believe that increasing access to home ownership for people who currently rent in San Francisco is an important public policy goal. Home ownership creates stability of tenure and is one of the major ways that Americans build wealth and financial security. Given the limited land supply in San Francisco, condominium conversion is viewed as an easier way to expand homeownership opportunities than through new construction.

On the other hand, conversion usually results in significant tenant displacement because most renters cannot afford to purchase market rate condominiums. The other drawback is that conversion depletes the supply of rent-controlled housing over the long run. In order to avoid displacement and to conserve the supply of rent-controlled housing, San Francisco has for the past 22 years limited the number of allowable conversions to 400 units a year, half of which must be affordable.1.

In 2002, the Home Ownership Program for Equity (HOPE) ballot initiative sought to increase home ownership by raising the annual conversion limit to 1% of the housing stock (an average 3,500 units per year) for 25 years. The program would have potentially reduced the rental inventory by 85,000 units over this time period. To deal with displacement the initiative provided that all tenants who chose not to purchase would receive lifetime leases subject to current rent controls. The voters rejected the initiative by a vote of 60% "no" to 40% "yes".

Recently, two different proposals have been developed which, like HOPE, also attempt to increase homeownership through condominium conversion. This paper discusses both. The first is referred to in this paper as the "Market Based Home Ownership Program" (MHOP), and the other as the "Community Land Trust Program". Each approach has different goals, and in some respects the two are competing proposals.2.

The MHOP is a market-based approach. All units sold under the program would be at market prices. The measure attempts to mitigate displacement by sharing about 20% of the gain from conversion that accrues to building owners with tenants through purchase discounts, moving incentives and lifetime leases. The affordability would be through the purchase discount provided to tenants who buy their units.

The second proposal involves the creation of Community Land Trusts (CLTs). These are non-profit corporations that will purchase rental apartment buildings at their bulk or rental value, retain ownership of the land and then resell the dwelling units to tenants as leasehold condominiums. By retaining ownership of the land, a CLT can restrict initial sales prices in order to make the units affordable to building tenants. Resale prices will be similarly restricted in order to maintain long term affordability. The CLT model creates a form of limited equity ownership. Its purpose is to create permanently affordable housing as an alternative to rent control.

The City's official policy toward condominium conversion is expressed in Policy 2.3 of the Housing Element of the General Plan, which states: "Policy 2.3 ... restricts the conversion of rental housing to other forms of tenure or occupancy". Conversion of existing rental apartment buildings to condominiums, stock cooperatives or tenant in common ownership depletes the supply of the City's more affordable housing stock. It also brings into conflict two desirable goals -- expansion of homeownership opportunities and preservation of the existing rental housing stock. While conversions to condos, co-ops, and tenancy-in-common expand the number of units available for purchase, they do so by reducing the number of units available for rent. As a result, existing and future tenants who cannot buy at that time can be displaced... In general, conversions should not shift the balance between ownership and rental housing, and should protect potentially displaced tenants to the maximum extent possible. Closely evaluating proposed conversions and limiting the number of conversions annually should achieve a reasonable balance between ownership and rental housing."

As of this writing, Supervisor Tony Hall has introduced one version of the MHOP concept and proponents of the Community Land Trust concept have drafted, but not introduced, legislation to enact their concept. Both pieces of legislation are likely to undergo many revisions.

Condominium Conversion Regulation in San Francisco

Before discussing the two proposals, let us first review the history of condominium conversion regulation in San Francisco. This background illustrates how the City has addressed the displacement and affordability problems presented by condominium conversion in the past. It also offers some insights into the difficulties of structuring conversion regulations.

Before 1979, the City did not regulate condominium conversions. In 1979, the Board of Supervisors amended the Subdivision Code to allow conversions of existing rental units to condominiums if a specific proportion of tenants indicated intent to purchase their units. No restriction was placed on building size. To qualify for conversion, 40% of the tenants in a building had to indicate in writing their intent to purchase. All tenants present at the date of filing of the conversion application had the right to purchase their units at a price no greater than the price offered to the general public. Following approval of a conversion, all non-purchasing tenants had the right to enter into or renew a lease agreement to occupy their units for up to one year. Property owners were required to bear the cost of moving expenses (up to a maximum of $1,000) as well as the cost of relocation assistance requested by tenants. All non-purchasing tenants aged 62 or older and/or permanently disabled were to receive a lifetime lease agreement and could be included in the calculation of the total number of units necessary to satisfy the tenant approval requirement. These leases gave tenants all the protections of rent control in place at the time.

The 1979 amendments also required that the City Planning Commission review conversion applications to determine whether any units to be converted were part of the City's low- or moderate-income housing stock. The code required that the sales prices of these units should be no greater than 2.5 times the maximum income that would be permitted under HUD definitions of low and moderate income households. Moreover, the owner of the property was to make such units available to low and moderate-income households at such a price for a twelve-month period. If these units did not sell during this period, the owner could offer them to the public with no price limitation.

In December 1981, the Department of City Planning reported to the Board of Supervisors on the effects of the 1979 conversion regulations.3 The findings of the report were based on files from the Departments of City Planning and Public Works as well as assessor records of sales for both newly constructed condominiums and conversions.

The report found that, "...only fourteen percent of [the tenant] signers [of intent to purchase forms] have purchased their units," during the time of the study. The report also found that 61% of units that had received conversion approval between January 1979 and March 1981 remained unsold at the time the report was released. In most of these cases, landlords had offered tenants cash payments in exchange for a signed intent to purchase form even though the tenants could not afford to purchase their units. In addition, the report noted that "...forty-one percent (41%) of condominium purchasers have claimed [a homeowner's tax exemption]; 59% have not done so. This indicates that the majority of condominiums have been sold to investors, buyers of second homes or homeowners neglecting to file exemption forms."

In March 1982, the Department of City Planning responded to a Board request for further information about the occupancy status of converted condominiums in the city. The Department pointed out that the 1980 US Census showed that the City had 6,258 condominium units--1,863 of these were renter-occupied, 548 were vacant and for sale and 506 were vacant for other reasons.4 In other words, almost half were either rented or vacant.

In November 1982, the Department submitted another letter to the Board expressing concern about the current condominium conversion policy, again citing the large number of unsold condominiums on the market,5 and stating that

...this Department has had great difficulty in enforcement of those provisions of the present Subdivision Code which attempt to discourage pre-application manipulation of tenants to facilitate a conversion. Some buildings have been cleared of all tenants before an application was filed in order to avoid opposition on the 40% intent to purchase requirement. This negates all tenant protections in the Code and frustrates its intent.

In November 1982 the Division of Surveys and Mapping within the Department of Public Works also presented information to the Board regarding departmental data on condominium conversions. It noted that "...of the number of buildings registered for conversion in 1983, about 60% are four units or less and about 80% are ten units or less. In other words, the majority of the would-be converters are small property owners." It also reported that annual registrations for conversions between 1979 and 1983 ranged from 611 units to 4,000 units. These fluctuations were less a response to market conditions than a reaction to proposed and actual changes to the local condominium conversion regulations and enactment of the 1979 Rent Ordinance.

In response to these issues and concerns, the Board placed a moratorium on condominium conversions. Mayor Feinstein vetoed the legislation because of the potential negative impact on property owners who had already made investments in anticipation of converting their buildings. She urged the Board instead to consider legislation limiting the types and number of allowable conversions.6

1. [The recommended legislation] once and for all sets the standard that large complexes built for rental housing and inhabited by tenants will no longer be threatened annually by the possibility of conversion.

2. It limits condominium conversion to owner-occupied buildings of six units or less and the number of such conversions to 200 per year. It is my understanding that the figure 200 is realistic under present economic conditions in that it covers the actual number of residential units converted in the past two years in this category.

The Board of Supervisors soon thereafter approved an ordinance limiting condominium conversions in accordance with the Mayor's recommendations.

Two very important conclusions can be drawn from this history. First, without a reasonable analysis of the actual market demand for converted condominiums, it is impossible to set a realistic annual limit on conversions. Second, most provisions for tenant purchase are easily abused and rarely effective.

PART I: The Market-Based Home Ownership Proposal

In its latest version as of this writing, the Market Based Home Ownership Program (the MHOP) proposes to transfer up to 5,000 units a year from rental to owner occupancy with a total transfer of 50,000 units. Apartment buildings of any size would be eligible if the following conditions are met:

1. 51% of the existing tenants of any apartment building must approve the conversion.

2. Each tenant shall be entitled to receive a 20% discount off the market price of his/her unit. The landlord shall propose a market price for the unit based on an MAI appraisal (an appraisal from a Member of the Appraisal Institute, an earned designation). If a tenant disagrees with the appraisal, the tenant may order his/her own MAI appraisal. If the two appraisals are within 10% of each other, they shall be averaged together; and the resulting average price shall be the established price of the unit. If the two appraisals are not within 10%, the two appraisers shall select a third appraiser, whose appraisal shall be the binding value.

3. If an existing tenant decides not to purchase, he/she shall have the right to remain in the unit under a lifetime lease subject to the San Francisco Rent Control Ordinance. This lease shall provide that, even if the San Francisco Rent Control Ordinance is ruled illegal by a higher court authority, increases in rent shall not exceed the increases in the SF-Oakland Consumer Price Index.

4. If a tenant elects to stay in the unit under the terms of a lifetime lease, and when that unit is eventually sold, the landlord shall pay 10% of the gross proceeds received from the sale of that unit to the Mayor's Office of Housing, which shall be used for the development of affordable housing in the City of San Francisco.

5. If an existing tenant decides not to stay in the unit, he/she shall receive a payment equal to 10% of the appraised value of the unit within 60 days of moving out of the building. The date of such a move shall be no later than one year after the date on which the landlord has received a Public Report issued by the State Department of Real Estate, or the date of recordation of a condominium map, if a Public Report is not required.

The lifetime leases and purchase discounts minimize the probability of involuntary displacement. The generous relocation incentive will probably encourage tenants to move, thus increasing the likelihood of displacement on a compensated basis. The 5,000-unit limit is quite high, which makes the market effects of this proposal troubling. Transferring 5,000 units annually from the rental to the ownership sectors runs the risk of destabilizing both markets. Finally, other than the eventual payment into an affordable housing fund of 10% of the sale proceeds of units sold as lifetime leases run off, the MHOP does nothing to address the loss of affordable units currently under rent control. Let us discuss these points in detail.

Impact on the Housing Inventory by Tenure

The MHOP seeks to expand the rate of condominium conversion in the belief that San Francisco should have a higher homeownership rate than it does presently. About 35% of San Francisco households own their dwellings. This is lower than the national homeownership rate of 66% but is closer to that of central cities like New York and Los Angeles. These cities are regional and international centers, and like San Francisco, they possess large rental housing sectors that serve as staging areas for immigrants from other regions of the country and the world.

EXHIBIT 1

Rental Units as a Percent of Total Housing Stock, San Francisco and Comparable Cities

Rental Units | Total Units | % Rental | |

| NYC | 2,109,292 | 3,021,588 | 69.8% |

| SF | 214,309 | 329,700 | 65.0% |

| LA | 783,530 | 1,275,412 | 61.4% |

| Chicago | 597,063 | 1,025,174 | 58.2% |

| Seattle | 133,334 | 258,499 | 51.6% |

| California | 4,956,536 | 11,502,870 | 43.1% |

| San Jose | 105,678 | 276,598 | 38.2% |

| United States | 35,664,648 | 105,480,101 | 33.8% |

The following table shows how San Francisco might change if it had a lower rental occupancy rate.

EXHIBIT 2

San Francisco with the rental occupancy rate of other cities

| IF San Francisco were: | Rental Units | % Rental | Change | Change | |

| Like | NYC | 230,155 | 69.8% | 15,846 | 7.4% |

| Like | LA | 202,546 | 61.4% | (11,763) | -5.5% |

| Like | Chicago | 192,018 | 58.2% | (22,291) | -10.4% |

| Like | Seattle | 170,060 | 51.6% | (44,249) | -20.6% |

| Like | California | 142,066 | 43.1% | (72,243) | -33.7% |

| Like | San Jose | 125,966 | 38.2% | (88,343) | -41.2% |

| Like | United States | 111,477 | 33.8% | (102,832) | -48.0% |

This table recalculates the size of San Francisco 's rental stock using the rental occupancy rates of the other cities shown in Exhibit 1. MHOP would transfer 50,000 units over 10 years and reduce the rental stock by 25%. A change of that magnitude would bring San Francisco closer to the renter occupancy rate of California and would significantly alter the social character of the city.8 The CLT program, which proposes to generate a maximum of 20,000 conversions over 10 years, would reduce renter occupancy by 10% and make San Francisco more comparable to Chicago . This would be a substantial change, but not as drastic as the MHOP. Moreover, it is unlikely that the CLT would change the social character of the city because of its strong emphasis in retaining tenants through its affordability provisions.

Market Effects

The MHOP proposal is likely to increase substantially the demand for rental housing, while at the same time reducing the existing inventory. This will occur for two reasons. First, the expected market prices (even after the 20% discount) are beyond what most tenants can afford to pay. At most, only 25% of all tenants (those with incomes more than $100,000 a year) would be able to purchase. This breakout is consistent with the income distribution of households in San Francisco living in unsubsidized rental housing. See Exhibit 3. Second, the 10% relocation incentive would probably encourage tenants who cannot buy to vacate instead of staying under lifetime leases. A large majority--75%--of all affected tenants would move either immediately or over time.9

According to the Bay Area Economics tenant survey cited in Exhibit 3, 23% of all tenants move within one year and close to 55% after five years. Less than 22% of all tenants remain in their dwellings for 10 years or longer regardless of whether the units are market rate or under rent control.

EXHIBIT 3

Household income of renters in non-subsidized units, San Francisco, 2001

| Household Income | Number | % |

| < $15,000 | 50,600 | 25% |

| $15,000 to $24,999 | 24,400 | 12% |

| $25,000 to $34,999 | 21,000 | 10% |

| $35,000 to $49,000 | 23,200 | 11% |

| $50,000 to $79,999 | 27,300 | 13% |

| $80,000 to $99,999 | 7,900 | 4% |

| >$100,000 | 50,600 | 25% |

| Total | 205,000 | 100% |

Note: Subsidized and assisted rental sector is about 36,000 households and is not included in the above table.

Sources: Bay Area Economics, 2001. U.S. Census Bureau, 2000.

Hence, if the program were to operate at its maximum level of 5,000 units per year for ten years, the city's rental market would experience a net increase in demand for 2,200 additional units each year for 10 years. This could be offset by rental construction at its historic rate of 400 rental units a year, most of which is affordable housing. The net average shortfall then would be 1,800 units a year cumulating in 18,000 units over 10 years. That would effectively wipe out the city's rental vacancy factor after two to three years. If job growth picks up enough over the next few years to attract newcomers to the city, the net shortfall would be even greater.

Most of the loss in rental units would come from the rent-controlled sector--that is, units built before 1978, where landlords have the greatest incentive to convert. Some of the new construction offset discussed above would be affordable-rate housing but not all. MHOP would therefore reduce the rent-controlled sector by a total of about 20,000 units, or 16%, if one adjusts the total units under rent control for rented single-family homes. Exhibit 4 below breaks out the rental housing inventory by sector and building size and is useful in evaluating the potential market effects of the MHOP.

Note: Subsidized and assisted rental sector is about 36,000 households and is not included in the above table. Sources: Bay Area Economics, 2001. U.S. Census Bureau, 2000. Hence, if the program were to operate at its maximum level of 5,000 units per year for ten years, the city's rental market would experience a net increase in demand for 2,200 additional units each year for 10 years. This could be offset by rental construction at its historic rate of 400 rental units a year, most of which is affordable housing. The net average shortfall then would be 1,800 units a year cumulating in 18,000 units over 10 years. That would effectively wipe out the city's rental vacancy factor after two to three years. If job growth picks up enough over the next few years to attract newcomers to the city, the net shortfall would be even greater. Most of the loss in rental units would come from the rent-controlled sector--that is, units built before 1978, where landlords have the greatest incentive to convert. Some of the new construction offset discussed above would be affordable-rate housing but not all. MHOP would therefore reduce the rent-controlled sector by a total of about 20,000 units, or 16%, if one adjusts the total units under rent control for rented single-family homes. Exhibit 4 below breaks out the rental housing inventory by sector and building size and is useful in evaluating the potential market effects of the MHOP.

| Building Size (# of Units) | Renter Occupied | Rent Controlled | Market Rate | Subsidized |

| 1 | 45,600 | 22,200 | 17,200 | 6,200 |

| 2 | 24,400 | 19,700 | 700 | 4,000 |

| 3-4 | 32,700 | 27,400 | 1,300 | 4,000 |

| 5-9 | 25,500 | 22,500 | - | 3,000 |

| 10-19 | 26,800 | 22,100 | 1,000 | 3,700 |

| 20+ | 50,300 | 31,700 | 2,900 | 15,700 |

| Total rental units | 205,300 | 145,600 | 23,100 | 36,600 |

| Total buildings with 5+ | 102,600 | 76,300 | 3,900 | 22,400 |

| Units in bldgs with 5+ units as % of total units | 50% | 52% | 17% | 61% |

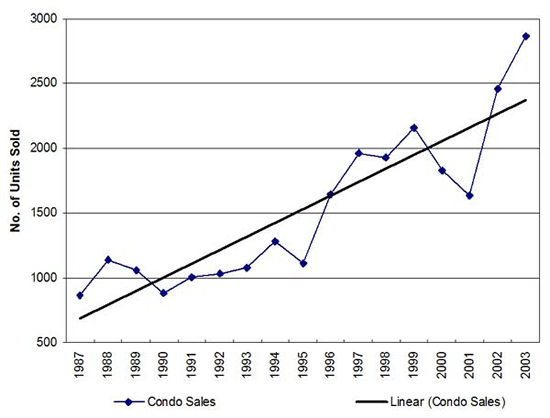

The MHOP proposal also risks destabilizing the condominium market, which may not be able to absorb 5,000 additional conversions annually. This conclusion is derived from an analysis of historic sales for condominiums in San Francisco as shown in Exhibit 5. It displays the time series for annual condominium sales from 1987-2003.

EXHIBIT 5

Note: Sales only includes condominiums and stock-cooperatives-both conversion, existing condominiums and new construction. Source: San Francisco Board of Realtors

Note: Sales only includes condominiums and stock-cooperatives-both conversion, existing condominiums and new construction. Source: San Francisco Board of Realtors

This time series reveals that condominium sales are highly cyclical, and more so than single family sales, which are not shown here. The trend line in the chart can be interpreted as the long-run demand for condominiums after adjusting for factors that cause sales to rise and fall in the short term. One could therefore forecast the long-run demand for condominiums by extrapolating the long-term sales trend line12. Thus, the long run demand in 2015 would be about 3,700 units, which would imply that the market could only absorb an average of 750 additional condominiums a year, and that would include both new construction and conversions. This number assumes that new construction of condominiums continues at its historic rate and the average condominium turns over once every seven years, about at the same rate as for single family homes. Even if one upwardly adjusts the trend line to account for additional demand represented by tenancies-in-common (currently about 700 units a year13) and demographic changes, this model still says that the condominium market could not absorb more than another 1,100 newly constructed and converted units per year over the next ten years.

It is true that a surplus of condominiums may reduce their price and make ownership more affordable throughout the city. However, that may not occur because housing markets are segmented by location and quality. The price effect will depend on the condition and quality of converted units and their locations in comparison with existing market supply. Thus, a 1-bedroom unit is not necessarily competitive with a large flat, and a condo in the Richmond is not necessarily competitive with one in Noe Valley . Unsold inventory can be rented if the current price level is depressed, which might become more profitable than conversion if the MHOP increases rental demand. An initial drop in prices might also be short-lived due to quantity adjustments, e.g. less new construction, fewer landlords choosing to convert, or more owners holding on to their units and renting them out instead of selling. Effects like these occurred in 1981 when the condo market was also glutted (see --Condominium Conversion Regulation in San Francisco , p. 3).

Public Finance Impacts

One of the beneficial side effects of the MHOP program is its fiscal impact. 50,000 units converted from rental to ownership over 10 years would create a continuous stream of tax revenues. Taking account expected appreciation in property values over a 10 year period, and assuming a general fund tax rate of 0.56% and a transfer tax rate of 0.68%, the program would increase property taxes in the general fund by $520.6 million and real estate transfer taxes by $186.1 million as cumulative totals over a 10-year period. Property taxes in the general fund will be 9.5% greater by the end of 10 years than would have been the case in the absence of the program. In addition, turnover of converted units would make this stream of property tax revenue even higher the farther out in time one goes. Given that property taxes today comprise only 25% of general fund revenues, the net effect on the general fund would be about 3%.

It should be noted that if the market is unable to absorb 5,000 units a year contemplated under this proposal, the resulting excess market supply could depress sales prices of condominiums, both new and existing. If so, the tax revenue stream may be considerably lower than estimated here.

Affordability

San Francisco would also gain from the 10% mandatory contribution to the city affordable housing fund out of the sales proceeds of units as lifetime leases run off. Over a 10-year period, these contributions could reach from a cumulative total of $120 million if 10% of all affected tenants stay with lifetime leases, to a high of $370 million if 30% of tenants take lifetime leases.

The number of affordable units which these funds could generate depends on the availability of other subsidies from state and federal sources. If such subsidies are generously available, then the city could leverage these funds at a ratio of 4 to 1 and help finance from 1,700 to 5,300 affordable units over a 10-year period after adjusting for inflation of construction costs. If other sources of subsidies are more constrained, then the city would likely only leverage at a ratio of 2 to 1, and produce from 1,100 to 3,200 affordable units over the same period.

In addition, one other qualification must be made here. Given the long lead time required for construction of affordable housing, we should not expect that more than half of this potential will be realized in the form of units completed and available for rent or sale at the end of 10 years after the start of the program. Hence, the net effect after 10 years would only be at the very best either about 2,700 at the higher leverage ratio or about 1,700 at the lower leverage ratio. In either case, this would replace only a fraction of the 22,000 rental units lost during this period and still leave the rental market with a substantial long-term shortfall for many years to come.

PART II: The Community Land Trust Program

The proposed Community Land Trust Limited-Equity Condominium Conversion Ordinance represents an effort to create a form of condominium ownership that is affordable by low- and moderate-income households. The Ordinance would allow CLTs to convert and sell apartments as condominiums subjects to initial sale and resale restrictions in order to achieve both current and permanent affordability. The CLT Ordinance would apply only to rental apartment buildings with seven units or more.

Land trusts in the form of Conservation Land Trusts have been widely used for controlling the use and value of undeveloped land outside of urban areas. CLTs, on the other hand, acquire developed or undeveloped land in order to create affordable housing. They rely on various sources of public financing, including Community Development Block Grants and HUD HOME Block Grants, state affordable housing loans, local government loans, and federal tax credits to extent applicable.

According to the provisions of the proposed Ordinance, a CLT would buy an apartment building from a landlord, retain ownership of the land and sell the condominiums to the tenants at prices based upon their household income. The CLT would purchase the building based on the rental value of the aggregate units and not their higher value as condominiums.

For example, a one-bedroom unit that might sell as a rental income property at between $160,000-$175,000 might fetch a price as high as $450,000 if converted and sold to homebuyers as a condominium. Several factors account for this differential in value.

1. Owner-buyers tend to have higher income and wealth and can pay more for housing.

2. Federal and state tax subsidies available for homeownership tend to boost demand.

3. Condominiums tend to be better equipped with amenities, including updated kitchens and baths.

4. Rent control tends to depress the value of rental apartments.

The CLT would retain title to the land and lease a proportionate interest in the land to each condominium buyer for a term of 99 years, creating thereby a leasehold condominium. Sale and resale restrictions would be written into each land lease for the entire life of the lease. The CLT would continue to own the unit and an equivalent share of the common area leasehold for all units not acquired by tenants. The converted units would be sold at the lesser of (a) a price affordable to a tenant so that monthly payments are not more than 35% of their household income, or (b) the market price as determine by appraisal. Tenant income of initial purchasers and resale buyers would be certified by the Mayor's Office of Housing.

Conversion would be permitted only if the following conditions are met:

1. A majority of tenants (51%) sign "Intent to Purchase" forms

2. The landlord agrees to sell the building to a certified CLT that is willing and able to act as the conversion agent on behalf of the tenants

3. All units in the building are subject to permanent rent and resale restrictions intended to preserve long-term affordability

Tenants who chose not to purchase would receive (1) a lifetime lease as long as they reside in their unit, (2) a lifetime option to purchase as long as they remain in their units, and (3) all other protections provided by San Francisco rent stabilization laws. Two thousand units would be permitted to convert under this program each year, but unused allocations could be carried over to the following year except that no more than 3,000 units could be approved for conversion in any 12-month period.

The legislation would also create a city wide Conversion Board to monitor CLTs and establish rules and regulations controlling their activities and behavior. All CLTs would be required to register with the Conversion Board annually and be certified as in compliance with the Board's rules and regulations. To be certified, the Conversion Board would require that a CLT (1) retain ownership of the land in perpetuity, (2) provide for automatic membership to all land lessees and non-purchasing tenants, and (3) have adequate resources and technical capacity to act as a landlord, steward and manager of property. Any purchaser of CLT land must also be a registered CLT in good standing, and the Conversion Board must approve the terms of any such sale of CLT land.

Program Potential

How large could the program be and how many units might be converted?

A substantial number of renters are interested in owning a home. A survey conducted by Bay Area Economics for the S.F. Rent Board in 2002 showed that 44% of renters surveyed indicated that they had been looking to buy sometime in the prior three years. However, only half of the 44% wanted to own in San Francisco . More revealing is the fact that 27% of this group (14% of all renters surveyed) indicated that they were interested in buying a condominium. The survey did not determine how many of those interested in buying a condominium would choose to own the units they currently occupy nor whether they would be willing to own a condominium subject to resale restrictions.

| Considered Purchasing a Unit in Last Three Years | ||

N | % | |

| Yes | 254 | 44% |

| No | 326 | 56% |

| Total | 580 | 100% |

| Locations Considered | ||

N | % | |

| SF | 138 | 49% |

| Elsewhere in Bay Area | 92 | 33% |

| Elsewhere in CA | 24 | 9% |

| Other | 28 | 10% |

| Total | 282 | 100% |

| Type of Unit Considered for Purchase | ||

N | % | |

| SF Home | 161 | 53% |

| Townhouse | 31 | 10% |

| Apartment/Condo | 82 | 27% |

| Live/work Loft | 11 | 4% |

| Other | 19 | 6% |

| Total | 304 | 100% |

| Reasons for Not Purchasing | ||

N | % | |

| Did not like available choices | 23 | 7% |

| Could not afford unit sought | 164 | 53% |

| Did not have down payment | 39 | 13% |

| Uncertain about financial security | 25 | 8% |

| Other | 58 | 19% |

| Total | 309 | 100% |

Source: Affordable Housing Survey, Bay Area Economics, 2002

However, these preferences are probably affected by the fact that 53% of those surveyed who expressed interest in owning indicated that they could not afford to buy the type of unit they preferred. In addition, 13% did not believe they had a sufficient down payment and 8% were uncertain about their financial ability to maintain ownership. Thus, about 75% of the renters surveyed who were interested in buying could not afford for one reason or another what was available in the market.

If 14% of all San Francisco renters are interested in owning a condominium we would expect a similar proportion would be interested in owning their own apartment. If we apply this percentage to the number of rent-controlled units in buildings with 5+ units, we end up with about 10,700 households. The actual number could be less because we do not know how many of those wishing to own condominiums would be willing to participate in a limited-equity arrangement. Limited-equity tenure is an inferior form of ownership because it does not allow individuals to capture the full investment value of their dwelling. This limitation may restrict mobility since those who own limited equity dwellings cannot accumulate equity on a competitive basis in order to trade up to larger or better dwellings in the San Francisco housing market. On the other hand, the actual number could be greater than 10,700 households if the affordability constraint on preferences were removed. Many more tenants than indicated by the results of this survey might be interested in limited equity condominiums if CLTs can in fact offer units at affordable prices.

Given these considerations, we would estimate that the number of potential renter households interested in limited equity condominiums is likely to range from 8,000 to 17,000. This is substantial in terms of the goals of this program. Creating 10,000 to 17,000 limited equity condominiums over a 10-year period would represent a significant contribution to the city's affordable inventory, which currently stands at about 36,000 units. Moreover, under the lease structure and resale restrictions that CLTs would use, these units would remain permanently affordable longer than would most affordable new construction, which is required to remain affordable for only 50 years under regulatory agreements.

The program would target both low and moderate-income renters, however the majority of households served would be low income. IRS requires that non-profit corporations devoted to housing provide substantial benefits for low-income people in order to meet "safe harbor" rules. This means that CLTs would be obligated under federal and state tax law to allocate at least 70% of their housing activities to serving households at 80% of the area median income or below.

The CLT model appears to have the following advantages:

1. It provides for homeowner opportunities for tenants at a broad range of income levels

2. It prevents displacement of current residents

3. It preserves the affordability of the existing housing stock

4. It creates permanent affordability

At the same time, this proposal involves an untested program and the establishment of a new institutional framework for creating affordable housing. The financing mechanisms and institutional procedures needed to make the program work do not now exist. The City would have to devote financial and other resources to the implementation of the legislation if it is to have a lasting effect on housing affordability and expanded homeownership opportunities in San Francisco . The following analysis discusses some of these implementation issues.

Market Effects

The CLT program is not likely to have an adverse effect upon the rental market, even if up to 2,000 units annually were to be converted under the program. This program is intended to allow tenants to buy their building, and prices under the program would be substantially below what is available today in the condominium market. Given the income distribution of renter households as displayed in Exhibit 3, it is likely that 80% of all such households would be able to purchase. Hence, in contrast to the MHOP program, substantially fewer tenants would move and the resulting effect on rental demand would be negligible.

The market impact that is of some concern here is that some buildings converted to limited equity condominiums may contain illegal units, which would likely have to be removed as part of the conversion process. It is difficult to say how many might be removed, but it is possible to anticipate that as many as 100 such units could be lost for every 2,000 units converted.

Consumer Protection Issues

The CLT program requires a well-designed program of homeownership counseling and disclosure of maintenance liabilities. Homeownership involves not only benefits, but also risks. Among these are the financial risks associated with maintenance and repair expenditures, which can be unpredictable and substantial, especially in San Francisco , which has an aging housing stock. Moreover, rent control has caused landlords to defer maintenance because of the restrictions on passthroughs for capital improvements.

Condominium projects, whether conversions or new construction, are required by the state Department of Real Estate to analyze maintenance requirements and perform replacement-reserve studies at the time of the creation of the homeowners association (HOA) and every three years thereafter. These calculations are used to set appropriate maintenance and reserve requirements built into HOA assessments on owners.

However, such calculations do not cover two types of risks. First, replacement reserves may be underestimated. Some systems may wear out or fail sooner than anticipated. Funding unexpected repairs can be a major financial problem for market-rate condominiums, but it can be especially difficult for limited-equity condominiums.

Second, HOA members may choose to under-reserve in order to keep assessments low. This is a common occurrence. Reserves are set by majority vote of the members, who may have different preferences as to the level of maintenance in the building they own.

Both of these risks are heightened in the case of limited equity condominiums in older buildings, which normally have higher maintenance and repair costs than new buildings and less financial solvent members than in market rate projects. Most participants in the CLT program will be low- and moderate-income households with little savings, which will likely be exhausted by funding the down payment and closing costs for purchase of their units. Owners who have trouble meeting contingencies would have a great incentive to default and "walk," especially if their initial investment was small to begin with. It is extremely important therefore for CLTs to avoid defaults. The CLT Ordinance provides that in case of foreclosure, the unit would be released from the resale restrictions and sold at market so that the lender can mitigate its loss. The result would be a loss of affordable units. Lenders will require this as a condition making loans in the first place.

Therefore, any legislation empowering CLTs to perform conversions should require them to undertake a rigorous physical inspection of any building intended for conversion, educate owners at the time of conversion as to the financial risks of maintenance planning, and to develop a mechanism for handling unanticipated maintenance liabilities.

Start-Up Funding and Capitalization

CLTs are a new institution. They will be organized as tax-exempt non-profit corporations and operated by other non-profits, most likely existing non-profit housing development associations. Startup CLTs will require technical expertise in building condition assessment. They will also need expert knowledge of real estate taxation and finance in order to be able to structure transactions, including tax-deferred exchanges so as to compete with other income property investors in buying existing buildings.

They also need to be capitalized, and sources of funding need to be identified. The CLT needs capital for the following purposes:

• to finance acquisition of buildings from property owners before conversion

• to pay the costs of conversion (capitalized interest, improvements required to meet building-code requirements, and fees)

• to finance the equity position in units not sold to tenants and subject to life-time leases

• to provide equity for the purchase and ownership of units that may be subject to foreclosure

• to pay ongoing operating overhead, including staff, legal, and accounting fees

We estimate that a typical CLT would require approximately $11,000 of permanent capital per converted unit and $40,000 of capital per unit to finance acquisition and conversion.

The permanent capital could be raised from foundations or through state or federal community development block grants funds. The conversion capital could come from a revolving fund managed by the Mayor's Office of Housing and created through an allocation of affordable housing G.O. bond money. The MOH would in effect become a banker for CLTs. Because the conversion capital would be outstanding for a short period, an initial allocation from the upcoming bond issue would sufficient for the program to operate over a 10-year period. To convert 2,000 units per year for 10 years, would require an aggregate $21 million of permanent capital, and between $72 million and $36 million of working capital to fund expenses of conversion itself. The amount of working capital would also on the duration of the conversion process and the cost of upgrades and other improvements made during conversion.

Conclusion

Both of these proposals have advantages and disadvantages. The MHOP will generate the most market rate ownership units quickly and will probably include significant upgrading of the quality of converted units. However, it also risks destabilizing both the rental and condominium markets. The CLT Program, on the other hand, makes units now under rent control permanently affordable and will not adversely affect the rental market. However, because the CLT Program requires a complex implementation and start-up process, it will likely not generate many units in the short run.

SPUR believes that both approaches could be adopted on an experimental basis by restricting the MHOP program to buildings with 6 units or less and the CLT to buildings with seven units or more. This would make sense because the two programs serve different segments of the housing market. Doing this would eliminate the possibility that the CLT program would have to compete with the MHOP for the same buildings. If that were to happen, CLTs would be forced to buy buildings at the much higher condominium value, which would make it all but impossible to offer units to current tenants at prices based on their income.

SPUR believes that whether the City adopts one or both programs, it nevertheless should ensure that any expansion of condominium conversion would be consistent with the other goals of the city's housing policy relating to affordability and displacement. The following are important principles that should guide the design of new approaches to condominium conversion.

• A condominium conversion program should maximize the number of affected tenants who can purchase their own apartments. This means half or more of the units have to be purchased by tenants in buildings converted either because the units are made affordable by means of sales price restrictions or by large purchase discounts. In order to avoid the abuses that led to curtailment of condominium conversions in the 1980s, when it was found that only a fraction of the tenants who signed intent to purchase forms actually purchased their units, a must stricter agreement to purchase needs to be crafted.

• The MHOP should also include controls on the resale of units purchased with discounts in order to discourage speculative turnover. This could be achieved, for example, by requiring the tenant buyer to pay from sale proceeds 100% of the discount to the city's affordable housing fund if he/she resells the unit within three years. The repayment of the discount would be decreased a percentage for every year the tenant purchaser stays in place beyond the first three years.

• If any rent controlled units (units built before 1978) are not purchased by tenants in place but vacated and then sold at market, the landlord or converter should contribute a a significant portion of the sales proceeds--25% or more--to the MOH citywide affordable housing fund. This contribution would help to compensate the city for the loss of affordable rental units 20. If resale restrictions are in place that would maintain long-term affordability, no such contribution should be required.

• Some provision should be made to legalize units that would otherwise have to be removed as part of the conversion process.

• If the city wants to authorized CLTs for condominium conversion a way must be found to capitalize them. One possibility is to use part of the upcoming affordable housing bond issue, should it pass in November for this purpose.

SPUR recommends that both approaches, with appropriate modifications consistent with the foregoing principles, be tested as pilot programs, with a three-year limit of 1,000 units--500 units for the MHOP program for buildings of six units or less, and 500 units for the CLT program for buildings with seven units or more. At the end of the third year, both programs should be evaluated and a determination made regarding whether either or both should be extended, expanded, or curtailed.

Endnotes

1.The City's official policy toward condominium conversion is expressed in Policy 2.3 of the Housing Element of the General Plan, which states: "Policy 2.3 ... restricts the conversion of rental housing to other forms of tenure or occupancy". Conversion of existing rental apartment buildings to condominiums, stock cooperatives or tenant in common ownership depletes the supply of the City's more affordable housing stock. It also brings into conflict two desirable goals -- expansion of homeownership opportunities and preservation of the existing rental housing stock. While conversions to condos, co-ops, and tenancy-in-common expand the number of units available for purchase, they do so by reducing the number of units available for rent. As a result, existing and future tenants who cannot buy at that time can be displaced... In general, conversions should not shift the balance between ownership and rental housing, and should protect potentially displaced tenants to the maximum extent possible. Closely evaluating proposed conversions and limiting the number of conversions annually should achieve a reasonable balance between ownership and rental housing."

2.As of this writing, Supervisor Tony Hall has introduced one version of the MHOP concept and proponents of the Community Land Trust concept have drafted, but not introduced, legislation to enact their concept. Both pieces of legislation are likely to undergo many revisions.

3.Condominium Research: Preliminary Progress Report, 1981 .

4 Letter from Dean L. Macris, Director of Planning, to the Board of Supervisors regarding proposed condominium legislation, March 15, 1982

5 Letter from Dean L. Macris, Director of Planning, to the Board of Supervisors regarding proposed condominium legislation, November 8,1982.

6Letter from Mayor Dianne Feinstein to the Board of Supervisors regarding Condominium Conversion Prohibition Ordinance and Annual Limitation of Conversions Ordinance, November 29,1982.

7These problems are discussed at length in San Francisco Legislative Analyst Report #016-02 and 017-02, "HOPE Initiative and Legislation", August 23, 2002 . Evidence from a similar law in Santa Monica , California in the 1980s confirms this finding.

8The HOPE program, which was rejected by the voters in 2002, would have made a much more drastic change by reducing the rental stock by 85,000 units over 25 years. According to Exhibit 2, that would have made San Francisco 's tenant breakdown more like San Jose 's.

9According to the Bay Area Economics tenant survey cited in Exhibit 3, 23% of all tenants move within one year and close to 55% after five years. Less than 22% of all tenants remain in their dwellings for 10 years or longer regardless of whether the units are market rate or under rent control.

10The shortfall effect before new construction is calculated using the following assumptions. For each 5,000 units converted annually 20% of tenants purchase, 60% take the relocation incentive and move, and 20% take life-time leases. Fifty-five percent of those who take lifetime leases move within five years of conversion and 80% within 10 years. The analysis also assumes renters living elsewhere in the city purchase 45 % of all units vacated either at the time of conversion or when tenants under lifetime leases move. This follows the methodology employed in The Conversion of Rental Housing to Condominiums and Cooperatives: A National Study of Scope, Causes and Impacts , U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development , Books for Business, November, 2001.

11Two factors explain the big jump in sales since 2001. Mortgage rates fell to a 40-year low in 2002-2003. That made condominiums more affordable and led to increased demand and sales. Second, the collapse of global stock markets in combination with the lower interest rates made returns in residential real estate more attractive than what was available in securities markets. This sparked even more buying, especially in the form of second home purchases. All this occurred during a period of modest unemployment. If unemployment has risen as high as it did in the recession of 1990, home buying would have been severely depressed, and prices which had reached unsustainable levels during the "dot.com boom" would have collapsed. It is unlikely that these conditions and this level of sales will continue over the next five years. If anything, prices are likely to dip slightly and then flatten out. Annual sales will also fall back toward its long-term average (the trend line) and probably dip below it.

12The equation for the line is: Annual Sales = -205931.15 + 103.72*Year. R 2 is 0.80.

13Estimated by Andrew Sirkin of Goldstein, Gellman, Melbostad, Gibson & Harris, LLP.

14See Appendix 2 for the assumptions used in making this estimate.

15Increasing general fund property taxes, which were $734,811,000 in 2003, at an annual average of 4.5% a year, would total about $1,091,999,000 after 10 years. The $103,695,000 million in general fund property taxes produced by the program (as shown in Appendix 2 below) would equal about 9.5% of this amount.

16This calculation adjusts the contributions for real estate appreciation and normal turnover.

17There is today a separate condo conversion pool of 200 units each year, if the units are sold at "affordable" levels. There are virtually no conversion applications for this because landlords prefer to pursue the market rate pool instead. Despite very low odds of a successful application, the mere existence of the 200-unit market rate lottery has driven the price of two to six unit buildings well above their economic value as apartment investments.

18Condominiums converted from the existing rental stock need not meet current building codes, be seismically upgraded, or have parking. Building inspections in the conversion process are intended to identify three types of conditions the owner or converter must remedy: (1) Work which was completed without required permits, (2) conditions which present safety hazards, such as poor fire egress or dangerous electrical wiring, and (3) energy and water conservation violations. These would cover illegal units.

19Jim Wasserman, "Home Owner Associations Undermined by Cash Shortages to Maintain Properties." Associated Press, 4/11/2004 .

20It should be acknowledged tha the "affordability" of rent-controlled units will be modified as tenants move out and the landlord moves the rent to the market.