This month, we are pleased to devote The Urbanist to Unbuilt San Francisco, an ambitious five-venue exhibition that provides an opportunity to confront visions for the region that never came to pass. If San Franciscans like to describe their city as “49 square miles surrounded by reality,” the visionary ideas that were too grandiose for even San Francisco to consider remain some of the most fantastic designs for any city in the world.

San Francisco was called from its windswept sand hills in great haste. Hills were cut, valleys raised, tidelands and bay waters filled as a rectilinear grid of blocks and lots was laid over the natural landscape of the peninsula. Although most “water lots” were filled and built out, some of these invisible territories remain today, submerged in an odd limbo between legal title and environmental protection.

By 1906, when most of the city was consumed by fire, San Francisco was an established city with global economic and cultural ambitions. No longer the rough upstart, it was filling out its peninsula and beginning to imagine reworking itself into a grand 20th-century metropolis, the “Paris of the West.” Daniel Burnham’s 1905 plan for the city, conceived at the behest of Progressive-era boosters who sought the city’s “improvement and adornment,” looked to fundamentally restructure San Francisco, blasting neo-baroque boulevards through its utilitarian grid and pushing staid beaux arts unity over its jumbled Victorian filigree.

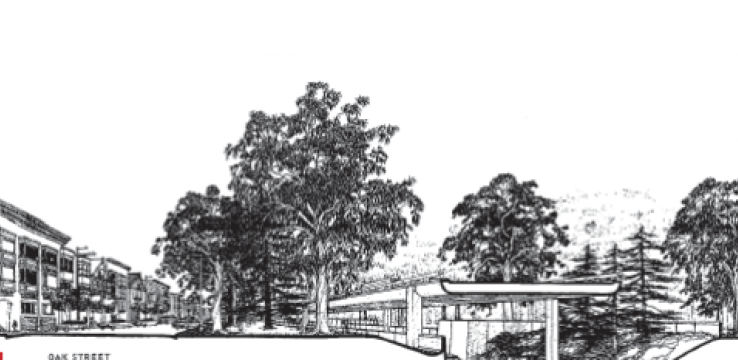

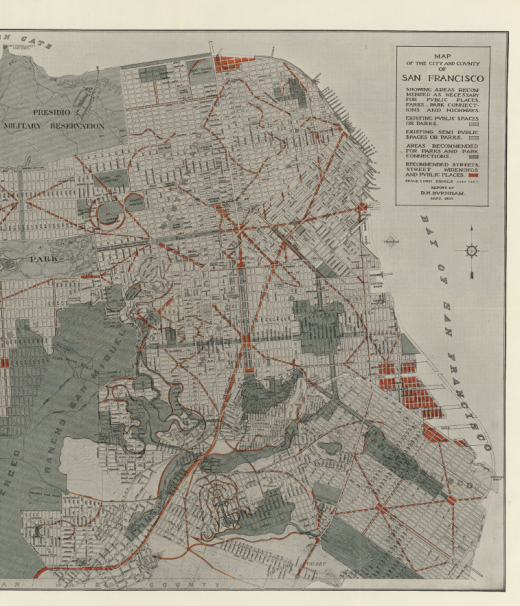

The Burnham Plan (1905) remains the most comprehensive attempt to reconfigure San Francisco. Burnham’s neobaroque diagonals and etoiles, inspired by those in Paris, would have cut across the grid, creating formal vistas to set off City Beautiful monuments. In spite of the opportunity presented by the following year’s devastating earthquake and fire, it was never implemented. (Courtesy David Rumsey map collection.)

Burnham’s plan ushered in a new preoccupation in San Francisco: civic debates over the architectural contours of the city, charged with moral and aesthetic consequence. What is worthy of this special place? What is appropriate to the city’s particular character? How do we solve pressing urban problems without eroding San Francisco’s dueling identities as picturesque yet provincial? Who is empowered to decide?

From its beginnings, San Francisco was a place to escape to and find oneself. It coupled entrepreneurial ambition with a licentious openness. For many people, the initial encounter with San Francisco was an experience of personal liberation — political, sexual, spiritual, pharmaceutical, natural. This sense of liberation cannot be unrelated to the city’s unique politics. The fierce affection that so many hold for this city, the intense aversion to change and the assertiveness of public debates over the city’s development has created a uniquely pressurized civic culture. It seems that, for many liberated transplants, San Francisco was perfect at the moment they fell under its irresistible spell, and everything that came after has been sacrilege.

Attempts to reconfigure the city according to evolving notions of progress, beauty and justice have often proved controversial and even traumatic. Certain sites in particular have been repeatedly revisited, with a succession of design proposals that highlight the ever-evolving visions of what San Francisco ought to be.

In the 1950s and ’60s, in San Francisco as in other American cities, urban renewal schemes leveled whole districts, precipitating conflicts over the shape of cities, the planning process and the exercise of power. Design schemes were repeatedly proposed and abandoned, reflecting shifts in the broader debates about architecture, urban design and development in the public life of the city.

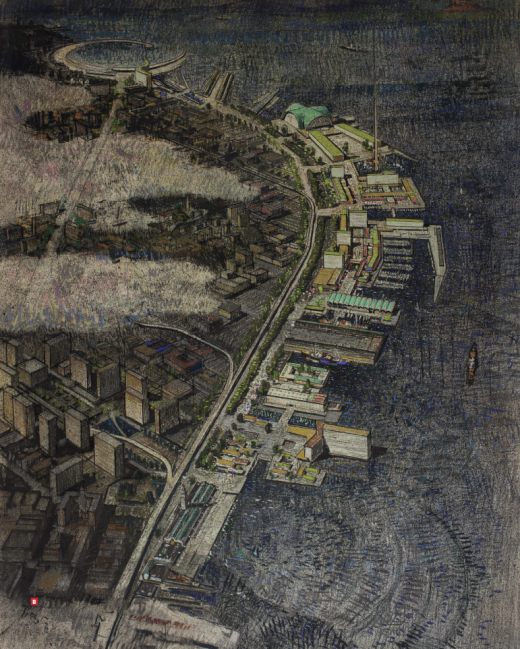

Ernest Born’s 1956 vision featured the now eradicated Embarcadero Freeway set against commercial and cultural development. (Ernest Born, Embarcadero Crescent View, 1956, pastel on paper. Ernest and Esther Born Collection. Courtesy of Environmental Design Archives, University of California Berkeley.)

Yerba Buena — where heavy industry flowered on sand dunes and bay fill — was the subject of more than a century of contentious wrangling. In the 1870s, financier William Chapman Ralston’s bid to extend downtown “South of the Slot” via New Montgomery Street and the Palace Hotel ruined him, but similar ideas would be revived by developer Ben Swig in the 1950s and drive indiscriminate demolition in the late 1960s.

Metabolist architect Kenzo Tange’s 1967–69 megastructure for Yerba Buena Center perfectly expressed both the ambitions and anxieties of San Francisco’s boosters and its redevelopment agency. The gargantuan garages and corporate facilities he proposed would have spanned Mission and Howard Streets, touching down only with massive spiral parking ramps. The plan offered a safely controlled extension of the Financial District, but its fortified design revealed the underlying assumption that South of Market and its residents were irredeemably “other.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the struggles of local tenants and hotel owners to resist eviction — encapsulated in Ira Nowinski’s singular photograph of two locals peering into a demolition site — captured the moral imagination of the city.

In this photograph from Ira Nowinski’s series from the 70s, residents contemplate a demolition site at Yerba Buena Center, where mass evictions led to protracted conflict — and numerous design schemes — over the district’s future. (“Demolition of the Milner Hotel, Fourth and Mission,” 1974/1979, Digital print courtesy of the photographer, Ira Nowinski.)

The legal victories of the tenants created an opening for new design ideas. Subsequent proposals, in addition to creating court-mandated affordable housing, emphasized public and cultural spaces but still maintained an inward focus. A series of gardens, follies and entertainments appeared, reflecting the heavily programmed “festival marketplace” approach of the period. At Yerba Buena Center, the arts became the bridge between the economic need for a convention center and the public’s desire for more humane and public-spirited uses for urban space.

In the 1980s, landscape architect Lawrence Halprin was hired to develop a series of gardens for Yerba Buena. While this imagined Chinese Garden was never realized, the overall Yerba Buena Gardens scheme was. (Norman Kondy, Associate, Office of Lawrence Halprin,”Yerba Buena Gardens, San Francisco, California Chinese Garden: The Lake,” (n.d.) Shadow box model, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania.)

As much as any site in the city, the Ferry Building has been the subject of debate and civic reimagining through a succession of proposals. Schemes for the “Foot of Market Street” date back to Willis Polk’s Ferry Building peristyle (1901), which imagined giving the city’s front door a monumental addition worthy of the period’s aesthetic ambitions. Later notions lopped off the clock tower to suit a modernist sensibility, projected new towers on piers in the water and carved canals that would create a Ferry Building island. Of course the Embarcadero Freeway would become the key design challenge: first, in efforts to screen, tame or deny its impact, with fluttering flags and trees boldly rendered and the freeway scarcely acknowledged in light pencil, and later, in the city’s soul-searching over whether to demolish it and what should replace it.

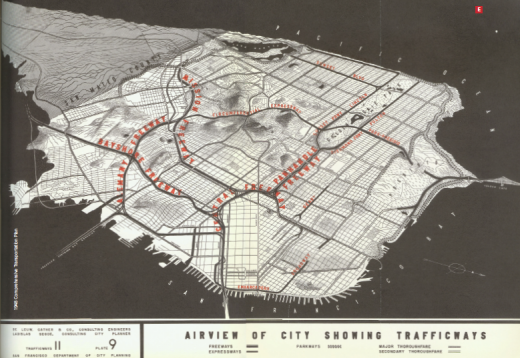

The efforts of engineers and architects to accommodate the automobile produced schemes that are some of the most shocking to contemporary sensibilities. A series of plans, including the 1948 Comprehensive Transportation Plan, imagined a city laced with freeways — like the now-infamous proposals for elevated structures in both the Golden Gate Park Panhandle and the Marina District. In 1948, traffic planners envisioned a massive parking structure that would extend from Third to Eighth streets between Mission and Howard, with freeway ramps alighting directly in the garage to solve the problem of urban parking and traffic once and for all.

A summary of proposed “trafficways” in San Francisco from the city’s 1948 Comprehensive Transportation Plan included the Panhandle Freeway connecting to freeways flanking Golden Gate Park, as well as a “Southern Crossing” bridge. These proposals and others would spawn citizen revolt in the 1950s and '60s. (1948 Comprehensive Transportation Plan.)

Indeed, attempts to beautify and sell urban freeways would consume a remarkable amount of design effort at midcentury, as landscape designers were deployed in support of traffic engineers’ increasingly embattled schemes. The best example may be Lawrence Halprin’s stunning 1964 ink drawings of the proposed Panhandle Freeway (see top of page). It was certainly not for lack of communicative prowess that the scheme fell victim to the Freeway Revolt.

The Region: Bridges, Burbs and the Bay

As midcentury San Francisco turned inward to grapple with the political and aesthetic challenges of urban change, much of the Bay Area was urbanizing for the first time. Throughout California, growth swallowed up orange groves, wilderness and mountaintops. The process of domesticating the natural landscape not only persisted but grew in scale and ambition. The bay was rapidly filled to make land for development, abetted by new institutions and new technologies. Development increasingly occurred not a handful of structures at a time, but in tracts of hundreds or even thousands. The experience of witnessing the conversion of wild and rural landscapes to homes and strip malls was widely lamented.

As the Bay Area region grew — its population far exceeding that of San Francisco — a different set of problems emerged. Where should growth occur and how could it be managed? Where and how should open space be set aside? To what degree should the natural landscape be transformed to facilitate and integrate urban development? Schemes to level mountains and fill the bay, dozens of unrealized bridges and freeways, even a new city in the Marin Headlands — all reveal the Bay Area grappling with these questions under pressure from rapid growth.

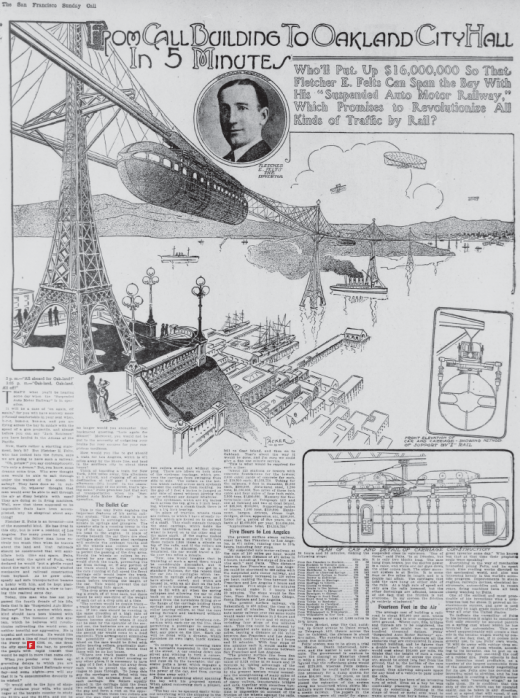

Major infrastructure — like BART and the Golden Gate and Bay bridges — can, in hindsight, seem inevitable, almost natural. But of course, these icons once seemed as speculative as they now seem certain. To prove this point, one need only look at the dizzying array of bridge and transit schemes that were never realized. In 1909, utopian engineer Fletcher Felts planned to build “The Suspended Auto Motor Railway,” which would have linked the Call Building with Oakland’s City Hall by way of a high-speed, carless railway bridge over the bay. Visionaries later proposed a second Bay Bridge, immediately adjacent to the first; bridges connecting San Francisco to Alameda and from Russian Hill to Angel Island to Tiburon; and a roundabout linking four bridges at Yerba Buena Island. A 1947 study compiled some 14 possible alignments on a single map. BART was the subject of great debate as well. Original 1956 plans showed lines to Marin and San Mateo and underground out to Geary Boulevard. Marin and San Mateo counties pulled out of the scheme in 1962.

This 1909 scheme imagined rapid transit from San Francisco to Oakland — and beyond — nearly 30 years before the Bay Bridge and more than 60 years before BART. (Courtesy California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside.)

Not only do the structures we build become familiar while the also-rans fade from memory, but they shape everything that comes after; they are reinforced by their spatial and economic embeddedness in the region we know. How might the Bay Area be different if different alignments had prevailed, if Marin had made its peace with taxes and transit? How might a Southern Crossing have shaped the region’s growth?

The most ambitious unbuilt schemes at the regional scale met their match in the rising environmental movement. Marincello, a proposal for a 30,000-person city in the Marin Headlands, was forged through the uncommon partnership of an oil company (Gulf) and an East Coast developer (Thomas Frouge). Marincello was approved in 1965, and initial construction was underway by the time it was scuttled by public outcry in 1972, becoming part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

The practice of filling the bay to make buildable land spread from Front Street to Mission Bay to Berkeley and Treasure Island. It appeared that the bay would be filled until only slim navigation channels remained. Then came the famous “Bay or River?” graphic, traced from a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers map projecting bay fill trends, that helped galvanize the Save the Bay movement in 1964.

Filling the bay was enthusiastically supported by some as a key economic opportunity. This led to a massive 1968 scheme to top San Bruno Mountain and fill and develop a Manhattan-sized area of the bay was defeated by environmentalists. Boosters sketched the region with most of its hills targeted as fill material, an approach that could eliminate two endemic inconveniences at once. Plans referenced Dutch polders to demonstrate the feasibility of large-scale drainage. Perhaps even more far-reaching were schemes like the 1942 Reber Plan, which proposed to dam the bay at Richmond and south of the Bay Bridge, creating valuable freshwater reservoirs upstream, along with causeways for roads and rail and plenty of filled land. Typical of their time, these proposals gave scant attention to the critical dynamics of the bay estuary. (Interestingly, the specter of climate change has revived debates about large-scale engineering of bay hydrology, with competition entries showing massive tidal barrages plugging the Golden Gate when storm surges threaten.)

The 1942 “Reber Plan,” by John Reber, was one of several proposals that would not only have filled huge swaths of the Bay for development, but dammed it to produce freshwater reservoirs. (Courtesy UC Berkeley Library.)

The rise of environmental movements and the creation of regional institutions killed many such schemes, but a comprehensive approach to regional planning, such as that imagined by the Association of Bay Area Governments’ 1970 Regional Plan, remains elusive. Although discussions of integrated regional planning go back at least to the 1910s, interjurisdictional competition and a powerful home rule doctrine have stymied repeated campaigns, and the region’s footprint now reaches the Sierra Foothills. Resistance to sprawl is measured in precious lands saved from the bulldozer, but these are the remnant exceptions to a broader policy failure. An integrated region, with location-efficient growth, effective transportation infrastructure and protections for open space and agriculture, may represent the grandest unbuilt scheme of all.

Visual Civics and Visual Persuasion

At both the city and regional scales, the proposals on view in “Unbuilt San Francisco” reveal competing interests and value systems. Models, renderings and plans — the rhetorical tools of planning and design — engaged each period’s prevailing aspirations and anxieties, clamoring for the attention of decisionmakers and citizens. Concern with a particular site, problem or opportunity often spans a period of decades and presents a window into the city’s changing attitudes, politics and values. Every bit as much as the cities we build, the cities we imagine and reject reveal the collective creativity of the urban project and the imperfect civics of placemaking.