San Francisco is the best city in America at landfill avoidance. We report a 72 percent waste diversion rate, which accounts for our efforts to reduce and recycle, adjusted for population and employment changes. Our success is the product of aggressive state and local policy, a fruitful public-private partnership, and a sustained investment in outreach and public engagement. And although we are setting the nation's leading example, there's still more we can and plan to do.

Aggressive public policy

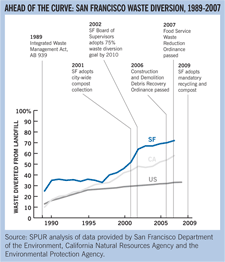

Much of our local success began with the State of California's leadership. In 1989, the Integrated Waste Management Act, Assembly bill 939, set goals to reverse our state's resource conservation patterns. At the time, 90 percent of our waste went straight into landfills. The act required cities and counties to divert 25 percent of waste by 1995 and 50 percent by 2000, allowing the materials in glass bottles, food waste, used tires, electronics, construction debris and more to be put to better use. The most aggressive waste diversion law in the country, the law motivated public and private investment in California's waste management infrastructure. The state helped develop new markets for recycled products by establishing environmentally preferable purchasing rules for state agencies and creating Recycling Market Development Zones, which provide loans, marketing and other assistance to businesses in specified areas that use waste materials to manufacture their products. It also required certain products such as newspapers and plastic bags to contain some post-consumer recycled content.

By 2007, California was diverting 58 percent of all waste, while San Francisco had more than doubled its 1990 rate to 72 percent, the highest diversion rate in the nation. The City began to make its greatest strides after 2000, following the adoption of a series of waste-related policies and programs. In 2002, the Board of Supervisors set a very high bar by adopting the goals of 75 percent waste diversion by 2010, and zero waste—or 100 percent diversion—by 2020. Curbside collection of food scraps for composting was pilot tested in 1996, and was approved for citywide rollout in 2001. A series of subsequent ordinances targeted specific waste streams, where a relatively simple change in purchasing or disposal practices could make a big difference. For example, the Construction and Demolition Debris Recovery Ordinance of 2006 required construction debris recycling, and the Food Service Waste Reduction Ordinance of 2007 required restaurants to use compostable or recyclable take-out containers. The City's Green Building Ordinance of 2007 required most new buildings and major renovations to be designed with equally convenient access to and adequate space for sorted waste streams. Because it looked likely that the 2010 goal would not be achieved through voluntary programs alone, in 2009, the City enacted the Universal Recycling Ordinance, requiring all properties to separate trash, recyclable materials and compostable waste in accordance with San Francisco's three-cart collection program.

This march of ordinances moved forward for a combination of reasons. For one, it became clear that better waste management would help us achieve other sustainability and climate action goals. Food composting, for example, avoids the production of a significant amount of greenhouse gases that otherwise would be emitted from food scraps sent to landfill. Second, we have a good civic culture around recycling that has permitted investment in recycling systems and facilities, and generally has produced high-quality sources of materials for recycling that have been in demand even while the overall market for recycled materials has fluctuated. Finally, our trash disposal contract at the Altamont Landfill is expected to reach capacity by 2014. It was clear that the longer we could delay the need for a new contract and additional landfill space by keeping food and recyclables out, the longer we could maintain favorable local refuse collection rates. City staff reports have recommended awarding San Francisco's disposal contract to Recology—formerly called Norcal Waste Systems—beginning in 2015 to establish a more integrated system and thereby create additional opportunities to increase recycling.

A fruitful public-private partnership

San Francisco has a strong and historic relationship with its waste hauler, Recology. Recology is parent to Sunset Scavenger, which serves the large residential neighborhoods, and to Golden Gate Disposal & Recycling, which serves the downtown area. Sunset and Golden Gate trace their roots in recycling back more than 100 years, when scavenger collectives went house to house in horse-drawn wagons to collect discards, and sorted those discards in the back of their wagons for reuse or recycling.

The City began regulating waste collection in 1921, and by ordinance, Sunset and Golden Gate received exclusive refuse collection licenses in 1932, a license Recology holds today. An employee-owned company, Recology is today involved in the collection, hauling, sorting, recycling, composting and transfer of San Francisco's waste. The companies are regulated by the Department of Public Works, which issues a rate order once every five years establishing the monthly fees they may charge customers for collection services. The City also sets year-over-year diversion goals for Recology, to further boost recycling.

At times in this long partnership, there have been questions about the company's exclusive deal, tensions over rates and concerns about how far we could cost-effectively push waste diversion. However, thus far it is clear that the arrangement has been beneficial for both environmental performance and the City's ratepayers. Rates are structured to provide financial incentives for recycling and composting for both Recology and its customers. While residents and businesses pay less (or nothing) to divert rather than to dispose waste, and pay based on the volume of trash disposed, Recology retains its revenues from composting and recycling services, which are tied to ever-increasing annual diversion targets by the City. The company has a deep investment in recycling infrastructure but not in a landfill, which creates an incentive to move as many materials to recycling and composting facilities as possible. Recology also has been innovative: willing to experiment, for example, with commingled recycling collection and food waste composting. The success of pilot or test programs helped pave the way to expanding recycling programs, and for the City to eventually make them mandatory.

A strategically labeled "landfill" bin at the California Academy of Sciences raise visitors' awareness about the destination point for non-recyclable trash. Image: flickr user rocketlass

A sustained investment in outreach and compliance assistance

The San Francisco Department of the Environment, which is largely funded by refuse collection revenues, has a team of zero-waste specialists whose outreach efforts have significantly increased participation in waste diversion programs. The team provides technical assistance, audits and literally knocks on thousands of doors to provide information when the rules change. The Department of the Environment also annually distributes $600,000 in grants to nonprofit organizations, to support innovation in reuse, recycling, composting, market development and education that could cost-effectively further increase waste diversion.

The future: zero waste by 2020?

While San Francisco is recycling more than any other large city in the United States, as much as 63 percent of waste put in the trash by San Franciscans and sent to landfill in 2005 was either readily recyclable or compostable.1 In the past 12 months, daily compost collection has increased by 25 percent, or 100 tons a day. Meanwhile, the amount of trash sent to the landfill is significantly down.

Will we be able to extend our success to 90 percent diversion or greater, as the marginal ease of doing so decreases? Recology and the Department of the Environment's zero-waste team think so, for a number of reasons. First, implementation of the mandatory ordinance has only just begun. There is still a lot of opportunity for source separation of materials, especially as many customers are signing up for the first time to participate in the compost collection program. Second, building on a tradition of willing experimentation, the City and Recology also may look to improve processing technologies to further separate compostables from trash once materials have been collected.

San Francisco's achievements can be attributed to ambitious targets, a cooperative arrangement with our waste hauler, and a culture of public support (sometimes spurred with incentives) for new programs. Although not all of these factors are portable to other cities, the wild success of viral media such as "The Story of Stuff" video about the production and consumption of consumer goods, as well as the growing number of states regulating things such as electronic waste, indicate that American culture and attitudes about waste are changing. As that happens, and cities take on sustainability and climate action planning, they can look to San Francisco for a model of how to ratchet their efforts up in waste diversion.

Endnotes

- Waste Characterization Study prepared for the Department of the Environment by ESA, August 2005. ↑