It lacks a rail rapid-transit network, but Seattle has a Department of Transportation that runs a fast, efficient bus system and has a specific plan to address climate change.

With severe geographical constraints, suburban-oriented regional agencies and state politics influenced by Libertarian ranchers, Seattle's transportation investments have lagged behind most other urban centers in the country. In fact, Seattle's transportation history has been a series of glorious tragedies and near misses, as time after time, the city almost funded and almost built rail networks. Still, San Francisco can learn at least four lessons from the would-be capital of the Pacific Northwest:

1. IT'S POSSIBLE TO MAKE BUSES WORK ON MARKET STREET

Lacking anything remotely like a rail system — let alone a rail rapid-transit network — Seattle has been forced to serve its urban centers with an unglamorous bus system. Up until 2005, Seattle did have a four-station, bus-only subway through its downtown, used by neighborhood-serving buses that entered the tunnel at either end. The tunnel is currently closed while being retrofitted for joint bus/light rail operations starting service in 2009.

To keep people moving in the downtown during the tunnel closure, the city and the bus operator made major improvements to surface transit, focusing on Third Avenue in the heart of the downtown. Like San Francisco's Market Street, Third Avenue is a four-lane arterial lined with retailers, office buildings and civic institutions, many of which need to provide access from the front. It works as follows:

- Cars are allowed on Third in order to maintain delivery and drop-off functions, but they are forced to turn right at each block. No left turns are allowed. These turn restrictions are rigorously enforced by the police. The effect is to eliminate all the delay associated with private vehicles without making the street "transit only."

- Buses are grouped into ‘A’ and ‘B’ lines, with bus stops provided every other block at the curb. Each group stops every four blocks, with the ‘A’ buses leapfrogging the ‘B’ buses, then the ‘B’ buses leapfrogging the ‘A's. The outside travel lane is used for stopping, and the inside travel lane for passing.

- City engineers tinkered obsessively with the traffic lights to minimize the chances that any bus would have to stop at a red light. In San Francisco, Market Street signals were once timed to favor buses, but the timing was shifted to favor cars as a “temporary” measure following the Loma Prieta earthquake — as an “emergency" measure, no environmental review was required.

- Because no bus is delayed by congestion or by other buses, the result is surface bus service that is faster than the former subway! The travel-time savings have been reinvested in frequency improvements. Faster buses and more frequent service have meant higher ridership, even though some people must now walk an extra block or two to their bus stop.

- Translated to Market Street, this would mean moving our bus stops to the curb lane, with each line stopping every other block (our blocks are longer than Seattle's) rather than every block as they do today. Streetcar boarding islands would need to be moved to the far-side of intersections and would be used only for streetcars. So, for example, the 5-Fulton and 6-Parnassus bus lines would stop in the curb lane as they do now, but only at, say, the even-numbered streets. The 7-Haight, 9-San Bruno, 21-Hayes and 71-HaightNoriega stops would move to the curb, at the odd-numbered streets. With cars forced to turn right at each intersection and the streetcar platforms moved to the far side of intersections, the inside lane can be kept congestion-free, and buses can pass streetcars on the right if need be. For more information, see www.seattletunnel.org.

Seattle has made efforts to better utilize its surface transit. Could San Francisco do the same?

2. IT'S POSSIBLE TO CHANGE THE CULTURE OF TRANSPORTATION

When Grace Crunican took the position of director of the Seattle Department of Transportation in 2002, departmental morale was at a low point, with little in the way of vision, and a lack of public trust that the department could deliver. To address these problems, Crunican did three things:

- She brought in a fairly small team of bright, energetic individuals and scattered them strategically throughout the department.

- She built public trust by starting small and delivering on promises for things that mattered to everyone. Specifically, she promised that all potholes would be filled within 48 hours of a complaint being filed. Their current success rate is 91 percent.

- She led a series of major planning initiatives, working across all modes, establishing a clear vision for the future of transportation in the city.

A unique aspect of Seattle's Department of Transportation is that it is dominated largely by women. Several managers found that this tends to make the department somewhat more collaborative, more integrated and more community-minded in its approach to transportation engineering. The end result is that Seattle's transportation staff members are now more creative and productive than in most comparable agencies. For more information, see www.seattle.gov/ transportation/.

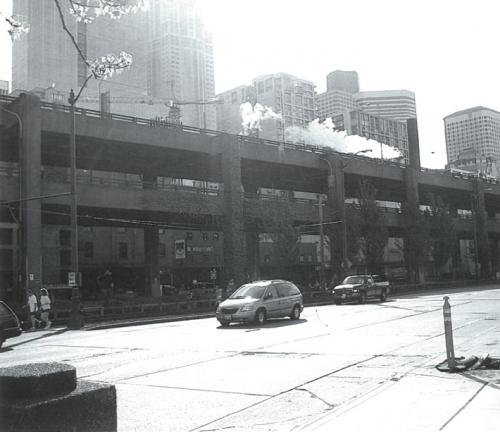

Seattle voters rejected aplan to replace the Alaskan Way viaduct with either a new elevated viaduct or a tunnel, and the city is poised to tear down the waterfront freeway and replace it with a surface road.

3. TEARING DOWN FREEWAYS IS HARD BUT GOOD.

Seattle is poised to tear down its waterfront freeway, the Alaskan Way Viaduct, and replace it with a package of surface roadway, transit and land-use improvements. While it shares a vintage and location comparableto San Francisco’s former Embarcadero Freeway, thesimilarities end there. This is a through highway carrying nearly a quarter of the total north-south through-traffic capacity in the city. Interstate Highway 5 provides about half, and city streets provide the other quarter. Eliminating the Viaduct is a big deal.

Still, voters rejected a “Big Ugly” option to replace the earthquake-damaged structure with a new viaduct, as well as a more costly option to partly bury the thing in a tunnel. in the November 2006 election, both options were on the ballot and both lost! Instead, Seattleitesare increasingly realizing that high-capacity highways are incompatible with great urban centers, and that a systemic approach to urban mobility can better meet the city's economic development and quality-of-life goals.

The city is developing a “Surface Transit" replacement for the Viaduct, including the following measures:

- Aggressive expansion of the new light rail and streetcar network

- Bus rapid transit and "rapid bus” improvements in a dozen corridors — Los Angeles has found that it's easy to get a 25 percent travel-time savings in major bus corridors, even without dedicated right-of-way, and that produces a 35 percent increase in riders

- Repair of the city's street grid to create more through streets

- Strategies to prioritize the movement of freight l Land-use changes in all of the city's “Urban Villages" it to reduce residents’ need to drive long distances for services. See http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/awv.htm.

San Francisco has nearly double the share of the workforce that sommutes with public transit (33 percent vs. 17 percent) while the share who drive alone is nearly 20 percentage points lower. San Francisco also has a higher share who walk to work or work at home. Among points of comparison, transportation stands out as a strength of San Francisco relative to Seattle.

4. GET SERIOUS ABOUT CARBON DIOXIDE

More so than just about any other city in the United States, Seattle takes carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases seriously. The city’s Climate Action Plan is among the most ambitious, with clear action steps and performance metrics for nearly every city department. Almost half of the action steps fall into transportation, the sector that produces about half of the Bay Area's carbon dioxide emissions.

San Francisco has its own Climate Action Plan. But where San Francisco's offers noncommittal words such as "expand" or “improve,” Seattle's plan forcefully says “construct 14 miles of” or "allocate $470,000 from,” and it follows these actions with clear, measurable performance targets. More importantly, the inter-agency and public discourse in Seattle, no matter the topic, always comes back to the impact on meeting the Climate Action Plan targets.

Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels began what has become the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement, which now claims more than 500 cities promising to comply with the Kyoto Protocol on global warming. In most cities in the United States, around half of greenhouse-gas emissions come from people driving, so there is no way to do anything meaningful about climate change without getting large numbers of people to switch to other modes of getting around. When Grace Crunican addressed the SPUR Board, she notedhow much of a difference this made in terms of the political support she received for transport policy changes, saying, “With all this emphasis on climate change, it has felt like we really had the wind behind our sails." Seattle has been willing to make real changes to the culture of transportation policy in order to live up to its environmental values. For more information, see www.seattle.gov/climate.

The monorail is perhaps Seattle’s most well-known mode of public transit infrastructure.