Overview

As California prepares to build North America’s first 200-plus-miles-per-hour high-speed rail track, the voices of doubt and hesitation become louder and more strident. Skeptics attempt to drown out confidence in the project. But if the current uneven economic recovery can offer any lesson at all, it's that confidence is a vital factor in correcting an economy — and it is also the most important asset of a public works project.

Skeptics have framed the question of high-speed rail as a major debate about whether or not we can afford it. This debate is happening both in Washington, D.C. and throughout California.

SPUR believes that high-speed rail is not just a worthwhile investment but a necessary one. We also believe that we can afford it.

California began building its current state freeway system in 1947, a decade before the federal government introduced (and began funding) the Interstate Highway System. Much of the debate and planning around building California’s high-speed rail assumes that the majority of the capital construction funds will come from the federal government — at least $38 billion in grants, loans and other financial support. That assumption is understandable: For the past century, major transportation projects — from bridges to rail — have always been funded with federal dollars. Federal government–supported bonds enabled the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge to be built, for example. And worldwide, major high-speed rail systems are generally built with funding from national governments.

However, given our national political dynamics, where a significant majority of elected leaders do not support government investment in domestic infrastructure, let alone in non-auto modes of travel, it is quite possible that significant federal investment will not materialize. This is not to be taken lightly: A future for the United States without major federal support for transportation projects is frightening and would lead to the further degradation of infrastructure and the loss of the nation’s economic competitiveness.

Unpleasant as it is to contemplate, this is a very tangible scenario we must prepare for. The good news is that even without federal support, California can pay for a high-speed rail system with resources generated within the state.

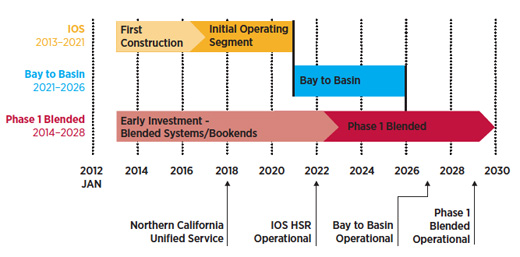

Figure 1

Construction phases for high-speed rail Just like the building of the Interstate Highway System, the construction of high-speed rail will occur in phases.

The full system that connects north to Sacramento and south to San Diego has been proposed, but the costs for these investments are not yet detailed.

California is the world’s ninth largest economy and the largest single economic entity worldwide without a high-speed rail system at least under construction. Far smaller economies and regions have built or are building high-speed rail. California’s gross state product is $1.959 billion — 188 percent larger than South Korea's gross domestic product (GDP), 143 percent larger than the Netherlands’ and 30 percent larger than Russia’s. In China, the high-speed rail connecting Beijing and Shanghai was built in less than three years. The total GDP of Beijing and Shanghai is about $550 billion, which is only half that of the ned San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles Metropolitan Statistical Area.

California is projected to add 20 million people between 2010 and 2050. The current proposed $68.7 billion high-speed rail system is far less costly and has significantly fewer environmental impacts than the more than $170 billion that would otherwise have to be spent by the state to expand airport runways and highways.

This article demonstrates how and why California can — and must — proceed with building highspeed rail.

What is the status of California’s highspeed rail system?

In the 1970s, leaders in California proposed a highspeed rail connection between Northern and Southern California. Although Amtrak has long provided train service along the Pacific Coast and south through the Central Valley to Bakersfield, there is no passenger rail service over the Tehachapi Mountains into the Los Angeles Basin. High-speed rail service would reduce the current San Francisco–to–Los Angeles transit trip from nearly nine hours (including a long bus trip over the mountains) to less than three hours, a speed that is highly competitive with air and much faster than auto travel.

In November 2008, 53 percent of California voters approved a $9.95 billion General Obligation bond (Proposition 1A) as a down payment on building such a system from San Francisco to Los Angeles and continuing to Anaheim. At the time, it was projected that the full statewide system would cost $33 billion. In 2009, the Obama administration identified $10.1 billion in federal funds for U.S. high-speed rail projects, $3.6 billion of which is dedicated for California. In 2011, the California High-Speed Rail Authority decided to invest the first major portion of its state bond funds to begin construction in the Central Valley portion of the segment. The federal government supported that decision and made the delivery of its $3.6 billion investment contingent on construction commencing in the Central Valley in 2012.

In recent years, the California High-Speed Rail Authority has further refined its extensive engineering drawings and produced several updated business plans closely detailing how and where the rail system will be built, and at what cost. This is a project that has been studied and scrutinized at an extremely high level of detail.

As of this writing, the State legislature has not yet authorized the sale of the state bonds to begin construction in the Central Valley.

How the train will be built

The latest business plan adopts the European approach to delivering high-speed rail: dedicated fast track in rural areas and use of existing, but often upgraded, railways in urban areas. This approach allows for a faster system delivery, which saves money and not only delivers benefits sooner but also generates revenue faster. Each section of the rail network will provide independent utility prior to the completion of a comprehensive statewide system of dedicated high-speed tracks. This so-called “blended” approach would run high-speed trains on existing rail as well as on new, dedicated tracks. This incremental method was successfully employed by the TGV, France’s high-speed rail system. (This sort of phased construction of infrastructure is not uncommon: Interstate 5 in California was begun in 1947 and not completed until 1979.

Since most current regional rail service in the state is diesel, the blended approach involves converting diesel train service (including Caltrain in the Bay Area) to electric service where trains will share tracks. This approach reduces costs significantly but still achieves a single-seat ride (that is, one train goes the entire distance from A to B, no transfers required) from downtown San Francisco to downtown Los Angeles and beyond.

There are three major phases proposed for the construction and implementation of high-speed rail:

1. Initial Operating Section (Merced to San Fernando Valley)

The first phase will include building dedicated high-speed rail tracks from Merced in the Central Valley south through Fresno and Bakersfield and then east to Palmdale and south into the San Fernando Valley, at the northern edge of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Construction will be completed by 2022, at which time the train could open for service for passengers traveling from the Central Valley into the Los Angeles region. The current business plan forecasts operating profits on this line, which means we can construct a high-speed train line from Merced to the Los Angeles area that requires no ongoing operating subsidies.

2. Bay to Basin System (San Francisco to San Fernando Valley)

In the second phase, to begin in 2021 and be completed in 2026, the dedicated high-speed rail infrastructure will be extended into San Jose from Merced. This segment will enable a one-seat ride from the Transbay Transit Center in downtown SanFrancisco all the way to the San Fernando Valley in the Los Angeles area.

3. Completed Phase 1 Blended System (San Francisco to Anaheim)

The third phase brings the dedicated high-speed rail system into Los Angeles’ Union Station and beyond to Anaheim. It also involves upgrading the passenger rail corridor between Los Angeles and Anaheim. A complete California high-speed rail system would extend service north from Merced to Sacramento and east from Los Angeles to Riverside and then south to San Diego. While this article does not assess the costs of these extensions, SPUR is committed to completing a statewide system that includes Sacramento and San Diego.

Figure 2 shows the construction process for the train system.

Figure 2

Construction schedule for high-speed rail The Initial Operating Segment (IOS) would connect the Central Valley with the Los Angeles area and begin service around 2022. With Bay to Basin service the train would then connect to the Bay Area and allow for a one-seat ride (meaning no transfers required) from San Francisco to the San Fernando Valley by around 2026. Under Phase I Blended, dedicated high-speed train service would connect into Los Angeles’ Union Station and beyond to Anaheim. Throughout the entire construction, there would be investments in the “bookends,” meaning investments in Caltrain and Metrolink as well as other regional rail systems in the Bay Area and Greater Los Angeles.

The benefits of high-speed rail

There are many reasons to pursue a high-speed rail system:

1. High-speed rail makes any two places on or near the line that were once far apart appear to be closer together by making travel between them easier and faster. Building a high-speed rail system across California would have a transformative potential on the economies of Northern and Southern California as well as the Central Valley. By decreasing the effective distance between parts of the state, highspeed rail shifts the market competitive structure within which people and firms make decisions about where to live, work and invest. In particular, high-speed rail can deliver economic growth opportunities to underperforming places (such as the Central Valley). Not only will the construction stage generate approximately 100,000 jobs for people in the Central Valley, but, once the train is operating, businesses may locate near rail stations to access other business opportunities throughout the state. Considering that the unemployment rates in most Central Valley counties are between 15 and 20 percent, getting people back to work and creating economic infrastructure to support a growing population is imperative.

2. High-speed trains will improve mobility by saving travel time and reducing congestion as travelers shift from air and auto to rail. California is falling behind its major competitors in the world economy due in part to its continued reliance on inefficient and expensive automobile and air travel. Congestion on our state’s roads results in $18.7 billion annually in lost time and wasted fuel. Flights between the Los Angeles and San Francisco metropolitan areas are the most delayed in the country, with approximately one out of every four flights late by an hour or more. The alternative to providing the same capacity as high-speed rail is to add 2,300 highway lane miles, four new airport runways and 115 airport gates. The costs of these expansions would exceed $170 billion over the next 20 years, more than twice the cost of the high-speed rail system. The projected number of riders diverted from the air system to the high-speed rail system would be more than 5 million in 2040 and would rise above 6 million by 2060. Based on the experience of Japan and Europe, high-speed trains can secure up to 90 percent of total air traffic for travel up to about 310 miles (slightly less than San Jose to Los Angeles) or half of all air travel for distances up to 500 miles (the distance from San Francisco to San Diego). Overall, from 2040 to 2080, Californians will save an average of 79 million hours per year by using high-speed rail.

3. High-speed rail will reduce pollution and help meet statewide climate change goals. With California’s growing population and consequent travel demand, there is no way to meet our greenhousegas reduction goals other than by shifting more trips onto cleaner trains. The rail system will mean 3 million fewer tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually. It will also result in 4 billion fewer vehicle miles traveled on California highways in 2040.

4. High-speed rail provides armature for the state’s growth. California continues to grow by nearly 500,000 people per year and is projected to surpass 50 million in population before the middle of the century. Most of this new growth must go into existing urbanized areas and will occur in communities adjacent to the high-speed rail system.

5. High-speed rail would help strengthen and improve commuter rail and regional intercity rail, increasing the viability of transit for intraregional commuting. The proposed alignment connects cities currently on or near the Los Angeles rail system with cities along Caltrain, for example. While there will only be one or two stations between San Francisco and San Jose, the sharing of tracks along the Peninsula corridor between statewide (high-speed rail) and regional (Caltrain) service will provide significant benefits to the Caltrain system by delivering statewide travelers who can easily transfer to go several additional stations north or south.

6. High-speed rail reinforces the knowledge economy sector by supporting face-to-face interaction and improved productivity. For the increasingly integrated economies of Silicon Valley and Hollywood, high-speed rail will facilitate greater innovation, exchange and collaboration, particularly because meetings can be continuous from one region to the other, without the hassle and inconvenience of air travel. The additional value of rail simply from the ability to do continuous work is estimated at $10 billion. (See “Hollywood vs. Silicon Valley," p. 14)

These are just some of the benefits of high-speed rail. But simply building a system does not guarantee that all the potential gains will be realized. Maximizing both ridership and gains to employment and income depends upon the ability of the market to invest in commercial development, housing and other productive facilities near the rail system. As noted above, such investments can have major impacts on both large economic agglomerations such as Silicon Valley as well as more isolated and economically strapped places like Fresno and other Central Valley communities.

But to realize the full economic benefits of high-speed rail requires an appropriate land use response. This means good planning for station area development as well as accessibility planning to connect travelers from high-speed rail stations to nearby employment and other destinations. If such investment does not occur, or if local opposition critically impedes it, the impact of high-speed rail will be significantly reduced.

To achieve the appropriate land use response to high-speed rail requires first the articulation of a statewide interest in high-speed rail as an important tool to shape development. But given that planning is a local function in California, there is a need to reconcile this conflict, particularly for an infrastructure investment with much broader economic benefits. SPUR’s 2011 Beyond the Tracks report proposed such a framework that combines local planning with statewide planning guidelines and oversight.

Yet this station area planning is only relevant if high-speed rail is actually built. Given this reality, the more immediate question is how to pay for the system.

Figure 3

Construction cost by category (in constant 2011 dollars)

The construction of the tracks and purchase of the right of way accounts for 2/3 of the entire cost of the high-speed rail system. The vehicles and stations themselves are a relatively small portion of the costs, as is the overall project management

Figure 4

Construction cost by geographic segment (in constant 2011 dollars) Connecting the high desert town of Palmdale into Los Angeles and from Merced in the Central Valley over the Pacheco Pass into San Jose account for over half the cost of the rail system. The long stretch from Merced to Bakersfield in the Central Valley accounts for less than 1/5 of the total cost.

How much will it cost to build California’s high-speed rail system?

The capital cost for a high-speed rail system from San Francisco through the Central Valley to Anaheim is estimated at $68.7 billion in year-of-expenditure dollars, using the baseline 2011 dollars and varying assumptions about inflation. Two-thirds of the construction cost is for building the tracks and acquiring the rights of way. Constructing stations, purchasing train cars and building the electrification systems comprise another 20 percent of costs, with the remainder being the administrative costs of program implementation. Each category includes contingencies of between 15 and 25 percent for unanticipated costs. In addition, the project includes a six-year schedule extension, which accounts for unforeseen delays in project funding. Speeding up construction or other changes could result in significantly lower costs.

Figure 3 (at top left), breaks out the categories included in the cost estimate.

Each segment has different costs, with the most expensive being San Jose to Merced, at $13.5 billion. Palmdale to Los Angeles will cost $12.3 billion, while Merced to Bakersfield will be $10.1 billion and San Francisco to San Jose’s Diridon Station will cost $5.6 billion, including the tunnel into S.F.’s Transbay Transit Center. The costs for different segments will vary with length and with features of the terrain and degree of urbanization. In urban areas, more expensive aerial structures or tunnels may be required.

Figure 4 (at bottom left), summarizes the capital cost for Phase 1 by segment, in base-year 2011 dollars. These are the individual alignment costs only and do not include systemwide costs like vehicle purchases and heavy maintenance facilities (nor does it include future rail extensions).

In 2008, when California voters approved a $9.95 billion bond to support high-speed rail, the entire project cost was $33 billion. In the 2009 business plan, the cost increased to $43 billion, and then increased again in the draft 2012 business plan to $98.5 billion. The final 2012 business plan reduces the cost to $68.7 billion. It focuses on beginning construction in the Central Valley while simultaneously making investments in the “bookends” — the urban areas in the Los Angeles Basin and the Bay Area — to improve regional rail service and take a blended system approach to the construction and operations by putting initial high-speed service on existing (and upgraded) commuter rail facilities. This approach saves both time and resources, as it has fewer environmental impacts.

How are we going to pay for it?

Funding sources include the federal, state and local governments as well as private sources, particularly a potential operator of the train system. Of these, only the state and secured federal grants are in hand. Proposition 1A authorized the state to issue $9.95 billion of general obligation bonds, $8.2 billion of which is estimated to be available for high-speed rail infrastructure construction after environmental, planning and support costs. The program has also received an allocation of $3.6 billion from the federal government.

In addition, the business plan assumes just under $5 billion from a combination of local, state and private sources.

The plan also assumes a $13 billion investment from a private operator who will invest once the trains begin operation around 2022. If the assumptions in the business plan are correct, the private operator will not require any additional operating subsidy and could provide more than $230 million from net cash flow for further investment in finishing the construction of the system. The remaining $38 billion is assumed to come from the federal government in the form of grants, loans and other financing support.

We hope the federal government does indeed invest in California’s high-speed rail system at this level, but

we also believe that California can pay for this on our own in the event the federal investment is lower.

California is wealthy enough and economically large enough to pay for high-speed rail. There are many different ways to pay for the system in theory. The official business plan presents one way, and this paper presents other alternatives in order to make our point. In short: We need to do this, and we can afford to do this.

If the federal government totally backs away from further investment in high-speed rail, there is one silver lining: We in California can still build high-speed rail by relying on a combination of road tolls, vehicle license fees, gas taxes, regional general obligation bonds, value capture mechanisms and revenues from the state’s cap-and-trade auctions. These local sources yield more than $2.7 billion annually. Over the 20-year construction of the high-speed rail system, these sources could replace the entirety of the expected $38.3 billion federal investment. In addition, they could also replace the current unspecified $5 billion from additional local, state and private sources.

While we are noting that most of the revenue from these identified sources can flow to the high-speed rail project, this is not an argument that these revenue sources should only apply to high-speed rail. For example, we think gas taxes should be much higher or replaced entirely with a vehicle-miles-traveled fee, but are only assuming an increase of 6 cents per gallon to help support the rail project. In addition, the vehicle license fee (VLF) should return to its historic levels of 2 percent of value. This article, however, assumes far lower and more conservative levels. Some may disagree with the specific fees we assume or the share dedicated toward high-speed rail. For each stream of revenue, reasonable minds can disagree. This article is meant to be a thought piece to demonstrate that with the proper mix of revenues, California can pay for high-speed rail.

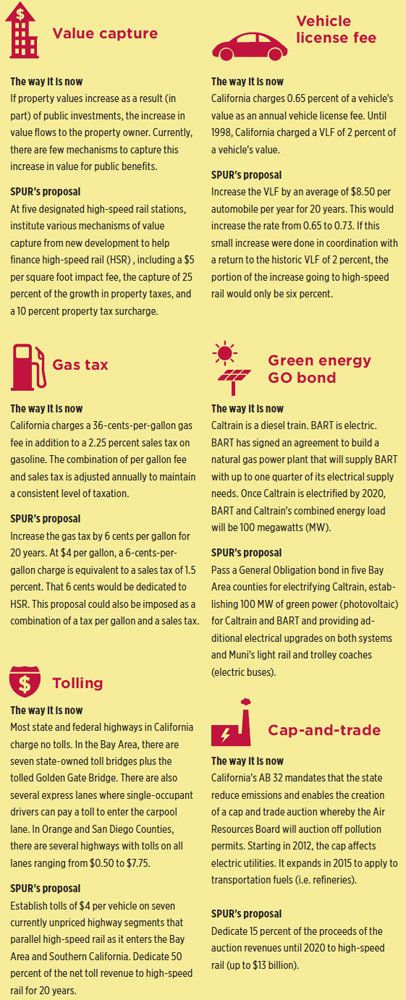

Our assumptions are as follows:

- An increase in the gas tax of 6 cents per gallon for 20 years

- Road tolls of $4 per vehicle on six highways that parallel high-speed rail as it enters the Bay Area and Southern California

- An $8.50 increase in the annual vehicle license fee (VLF) for 20 years

- A regional general obligation bond for green power for Caltrain and BART that also includes $1 billion for electrification and grade separation

- $13 billion from the annual state cap-and-trade auction revenues until 2020

- Various value capture tools (impact fee, tax increment, Mello Roos district) at five high-speed rail stations

Figure 5 compares the funding sources in the latest business plan with those in the SPUR plan (in year-ofexpenditure dollars). Below we explain each funding source in greater detail.

Figure 5

How to pay for California's high-speed rail system California can afford high-speed rail without future federal support. The sources of funding for high-speed rail identified here can generate over $43 billion towards the state's $68 billion high-speed rail project. The most significant sources of revenue are a dedicated six cent per gallon gas tax, a 15 percent share of the state's cap and trade auctions and the creation of $4 tolls on a few of California's highways.

Value capture

Value capture refers to policy tools that “capture” for the public some of the increases in land value generated by a public investment such as a new transit project. The idea is to ensure that the public receives some of the return on its investment as opposed to having all the increased land value accrue to private property owners. It also enables those funds to be reinvested back into the area to help pay for infrastructure improvements and other benefits (which in turn increase land values).

While planners often tout value capture as a way to generate additional funds for public benefits, the reality is that value capture in California is a far more modest source of funding relative to the other sources described here. In addition to the limited tools for value capture, the recent history of rail investment in California and elsewhere in the United States shows only minor increases in value for land adjacent to transit. SPUR believes it is critically important to further explore value capture mechanisms around high-speed rail, including what is proposed for San Francisco’s Transbay Transit Center. But we recognize that it has far less potential as a major funding source than other tools like tolling, gas taxes and cap-andtrade auction revenues.

Value capture encompasses a range of tools that extract some of the value created by the investment in the high-speed rail system. Some of the main tools include:

- Special assessment districts assess a fee on parcels in a particular zone that receives direct benefit from the investment in the high-speed train.

- Tax increment financing (TIF) is a mechanism whereby the growth in property taxes above a baseline is diverted and used to pay for specific local upgrades. Given that there are no longer redevelopment agencies in California with the power to use TIF within redevelopment areas, the closest tool is an Infrastructure Finance District (IFD). This operates like a TIF except that a smaller portion of the tax increment can be used to fund local infrastructure. IFDs capture the nonschool growth in the property tax only and are an appropriate tool for value capture around highspeed rail stations.

- Developer impact fees are one-time charges to developers in districts or cities, typically to pay for a portion of the surrounding infrastructure or other public benefits. These impact fees are used to finance costs associated with new development (such as feeder transit, schools, sewers).

- Joint development means that the private sector jointly develops property that is owned by the public sector (typically the transit agency).

In the case of high-speed rail, there are many needs that could be paid for with value that is recaptured by the public, including upgrades to local infrastructure, investments in bringing transit directly to the high-speed rail station, operating costs for maintaining transit or shuttle programs, gap financing for particular new development projects, economic development strategies focused on expanding and attracting businesses or for the actual station itself.

For the purposes of this paper, we only looked at value capture mechanisms focused on projected new development around five stations: San Francisco, Millbrae, San Jose, Los Angeles and Anaheim. Based on the combination of a $5-per-square-foot development impact fee, the capturing of 25 percent of the property increment and a property tax increase of between 6 and 10 percent (through establishing a Mello-Roos special property tax district), these tools would yield $400 million toward the high-speed rail system.

We recognize that San Francisco is already proposing its own system of value capture for the area around the Transbay Transit Center. The purpose of the analysis here is to demonstrate that it will be difficult for value capture to yield much in the way of funding for the overall system.

To generate more from value capture, we would have to apply value capture tools to existing development, as well as cover a larger geography around station areas. Even with such an approach, value capture would yield a small share of the total cost of high-speed rail. The lesson here is that value capture is not a significant source of funding for major statewide infrastructure. Instead we have to look to additional sources.

Cap-and-trade

Cap-and-trade is an enforceable program put forward by the California Air Resources Board (ARB) to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It is a central element of California’s Global Warming Solutions Act (AB 32). Under cap-and-trade, major sources of GHG emissions in California will be imposed with a GHG cap. The California Air Resources Board will distribute allowances, which are tradable permits of GHG emissions, to these capped sectors and will hold allowance auctions each year to allow market participants to acquire them. The first cap-and-trade auction will be held on August 15, 2012, and further auctions will be held through 2020.

The funds generated from the auctioned allowances can be used to further the purpose of AB 32, including for development and construction of the high-speed rail system. Additionally, high-speed rail is included within the scoping plan for AB 32.

The 2012–13 governor’s budget estimates that the cap-and-trade auctions will generate $1 billion in 2012–2013, the first year of the auction. According to recent estimates by the Legislative Analyst’s Office, the cap-and-trade program will generate annual revenue ranging from $2 billion to $14 billion (2012 dollars) between 2013 and 2020, depending on the amount of allowance issued and the price. Under Governor Brown’s plan, these revenues would be invested in clean and efficient energy, low-carbon transportation, natural resources protection and sustainable infrastructure development. The highspeed rail project is highly related to the low-carbon transportation category: By diverting people from automobiles and flights, high-speed rail will reduce 3 million tons of GHG emissions annually.

For this paper, we use the estimates from the Legislative Analyst’s Office for our assumptions about the revenue generated by the cap-and-trade auctions. If we assume that 15 percent of the revenue will be allocated to the high-speed rail project between 2012 and 2020, we project that the total amount of capand- trade revenues that can be used for high-speed rail is $13.05 billion (2012 dollars).

Tolling

A second major potential revenue source is road pricing. Specifically, we propose establishing tolls on all lanes on six key highways that run parallel to the high-speed rail alignment — 101, 280, 152, 5, 99, and 14. While tolling is likely a necessary mechanism to pay for general highway upgrades and to subsidize transit operations along the same corridors, we think there is sufficient potential revenue to support some of the initial capital costs for high-speed rail construction. This would be based on selling revenue bonds backed by the annual tolling revenue.

Our approach is different from regional highoccupancy toll (HOT) lane networks, which leave some unpriced lanes and thus can undermine the efficacy of pricing to affect commute patterns and location choices. By contrast, full lane tolling can vary based on time of day and on demand for road usage, encouraging commuters to switch to other modes of transportation, travel at less congested times or change routes. Tolling freeways at entrances and exits with FasTrak and license plate cameras would be more cost-effective.

Road pricing causes motorists to internalize the cost and impacts of driving, such as pollution and congestion. Pricing can affect commute choice, time of travel or route of travel. It also has the potential to reduce the number of vehicle trips. The higher cost of driving and use of revenue to fund transit can encourage mode shift.

There are some downsides and challenges to full road pricing. For example, pricing all lanes of the freeway will raise equity concerns. Drivers who cannot afford the toll are priced off the road or forced to choose alternative routes or modes that may be more time-consuming. Low-income motorists who have no alternative will pay the toll but may not value their time savings more than the toll.

Although freeway pricing raises numerous issues and concerns, it has great potential both to increase revenue and to affect individual travel choice. As a result, road pricing through tolls is an ideal candidate for a regional funding mechanism to help pay for highspeed rail construction.

We argue that tolling should occur in three regions of the state: the Bay Area, the Central Valley and the Los Angeles area. In our scheme, the Los Angeles and Bay Area tolls will pay for a share of the construction costs of bringing high-speed rail from the Central Valley over the mountains (Coastal Range or Tehachapi) and for upgrades to regional rail networks. In addition, tolls within the Central Valley will help pay for finishing the construction in the Central Valley. Actual tolls would range from $2 to $6 and would vary by time of day and distance traveled. The average toll would be $4, which is the amount used in our analysis.

Gas tax

The state of California taxes automobile gasoline at 36 cents per gallon, two-thirds of which pays for state highways, with the remainder going to cities and counties, primarily for streets and roads. In addition, California also assesses a uniform state and local sales tax percent on each gallon (reduced in 2010 from 8.25 percent to 2.25 percent as part of a gas tax swap with an increase in the cents-per-gallon tax and a decrease in the sales tax percent). California’s gas tax did not increase from 1960 until the 1990s, whereby it gradually rose from 9 cents per gallon to 18 cents. In 2010 the tax increased to 35 cents per gallon at the same time that the sales tax decreased from 8.25 percent to 2.25 percent. This latest increase, however, did not bring the total tax to its 1960 level. For example, in 2000 dollars, in 1960 California collected more than $33,000 per million vehicle miles traveled. By 1990, that take had declined to $6,500. The gas tax increases in 1990 brought it up to $9,300, still far below 1960 figures. Today the tax remains at roughly the same level, which would still put it well below 1960.

SPUR’s plan proposes an additional gas tax of 6 cents per gallon, which would generate $792 million annually. Assuming the tax would remain in effect for 20 years, it would generate a total of $15.84 billion for the project.

Vehicle license fee

California’s vehicle license fee (VLF) is an annual fee on the ownership of a registered vehicle. The state sets the level of the fee and distributes revenues to cities and counties. From 1948 until the late 1990s, the VLF was two percent of assessed value. Since then, it has been reduced several times and is currently 0.65 percent of a car’s assessed value.

There are currently 32 million registered vehicles in California, 22 million of which are automobiles. The average vehicle license fee per automobile is $66. Increasing the fee by $8.50 would make the effective rate of the VLF only 0.73 percent but would generate $187 million annually, or $3.75 billion over 20 years. This amount could be divided evenly among the three regions — the Bay Area, the Central Valley and Southern California — to pay for individual portions of the train infrastructure.

General Obligation bond

A final revenue source is a comprehensive regional General Obligation (GO) bond. Unlike the statewide high-speed rail bond from 2008, a GO bond at the county or regional level would need a two-thirds majority vote by the public to pass. This could change in a future election to 55 percent but as of this writing remains at a two-thirds threshold for passage. GO bonds have broad application as they are backed by the local property tax stream.

For the purposes of this analysis, we estimate a $2.5 billion regional GO bond from the five counties with BART and Caltrain: Alameda, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Francisco and San Mateo counties. Together, these counties have assessed values of over $800 billion.

This bond would pay for the following:

- $1 billion for electrifying Caltrain. This is the only portion of the GO bond that we are assuming as a replacement for the federal funds in the current business plan.

- $500 million for rehabilitation of BART’s electrical system

- $300 million for improvements to Muni’s trolley coach (electric bus) and light rail power system

- $700 million for creating 100 megawatts of solar energy, equivalent to the total load for BART and Caltrain

The $1 billion included here would offset some of the investment in the current business plan for highspeed rail.

Summary of revenue proposals

The revenue options listed above — value capture, cap-and-trade auction revenues, tolling, gas taxes, vehicle license fees and a GO bond — would yield more than $43 billion in purely state and locally generated funding.

We accept that the project currently has about $12 billion in state bonds and federal grants that can all be directly applied to the high-speed rail project. We also accept assumptions for a $13 billion investment from a private operator.

All told, the combination of SPUR’s plan and the existing sources yields more than $68 billion, the cost of the Phase I San Francisco–to–Anaheim system described in the 2012 business plan. If construction happens more quickly (based on having the funds earlier than assumed in the 2012 business plan), the entire Phase I project would cost considerably less than $68 billion. These savings could then be applied to expansion of high-speed rail to San Diego and Sacramento.

Getting on the right track

While based on conservative fiscal assumptions, the revenues described here are no doubt aggressive political assumptions. The current mood is that gas taxes are high and road tolls should only be used to pay for existing highways. However, part of the economic planning approach that SPUR supports is to consider the megaregion as its own semiautonomous economic unit. For the purposes of California, this is one of the reasons to suggest that we are perhaps one megaregion, not two. More importantly, the leading economic clusters of California — Hollywood and Silicon Valley — are increasingly integrated (for more on this, see “Hollywood vs. Silicon Valley,” p. 14). A physical rail linkage provides a much more substantial link than the current roadway and airplane connections.

Given the future economic importance of supporting this ongoing integration, we think it is worth pursuing these funding schemes as a way to fast-track the building of high-speed rail. Ultimately, this approach may mean the difference between a partial high-speed rail system with little utility and a full-fledged statewide system that offers a one-seat ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles in less than three hours. It is only on a train that travelers can watch their Hollywood-produced movie on an iPad designed in the Silicon Valley without ever turning it off for takeoff and landing.

--

Source: California High-Speed Rail Authority, Revised 2012 Business Plan, p. 2-30. (PDF available at 1.usa.gov/N7KZ5k)

Source: Tolling: SPUR analysis, 2010 AADT available at: http://traffic-counts.dot.ca.gov/; Vehicle license fee: SPUR analysis, http://dmv.ca.gov/fee_calc/feecalcfaq.htm