Ocean Beach—3.5 miles of sand and dunes on the city's edge—faces serious challenges from erosion and sea-level rise, which threaten local infrastructure and ecosystems. Photo: flickr / andrew_whalley_snaps

Ocean Beach, the three-and-a-half-mile stretch of sand and dunes along San Francisco's rugged Pacific coast, faces serious challenges. Part wild landscape, part urban beachfront, it draws a remarkably diverse three million visitors per year to stroll, bike, surf, walk dogs and enjoy the stunning natural setting. Its bluffs and sands—part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area—host two threatened bird species and an extensive dune system. Meanwhile, it's the site of an important sewage-treatment system that protects the ocean from wastewater pollution.

Ocean Beach also represents one of the first locations in San Francisco where the effects of climate change will come to a head. The existing shoreline, already located on fill and subject to erosion, will recede further as sea levels rise, exposing both natural and built resources to coastal hazards. We face difficult choices about how to manage these hazards while maintaining valued resources. Deepening these challenges is the complex array of federal, state and local agencies that oversee Ocean Beach, each with different responsibilities and priorities.

San Francisco's past two mayors convened community-led task forces, the Ocean Beach Task Force and Ocean Beach Vision Council, to address the challenges at Ocean Beach. But neither process included a pathway to implementation, leaving some participants frustrated and problems unresolved. The Vision Council submitted a grant proposal to the California State Coastal Conservancy, with partial matches from the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) and National Park Service (NPS), for a comprehensive long-range planning process to be led by SPUR.

But before the funding was even approved, the situation at Ocean Beach worsened considerably.

Erosion emergency: Response and criticism

In the El Niño winter of 2009–2010, powerful storms battered the bluffs of Ocean Beach south of Sloat Boulevard, resulting in dramatic erosion. In some locations, bluff tops receded 40 feet, undermining the asphalt of parking lots and the shoulder of the Great Highway, which was closed southbound for much of the year. The episode was the most serious in a series going back several decades.

The City's response—the construction of 425 feet of rock revetments (embankments of stone riprap)—has drawn criticism from environmentalists, who are concerned that such armoring often carries a heavy cost in beach and habitat loss. They ask whether an event as predictable as erosion at Ocean Beach can be meaningfully described as an emergency. Indeed, a similar episode in 1997 resulted in the construction of rock revetments that are still in place. With no policy for how to address the inevitable, the City repeatedly finds itself in a reactive posture, shoring up the bluffs under an emergency declaration with the lukewarm sanction of the Coastal Commission and National Park Service. The 2010 storm may have been an emergency, but it was hardly a surprise and, above all, reflects the lack of a policy framework to guide action in a crisis.

The environmentalist response may be a fair criticism, but erosion meanwhile poses a very real threat to a critical sewage-treatment complex that we depend on to protect coastal water quality. In the absence of another approach, this infrastructure, some of which lies underneath the Great Highway, must be armored against coastal hazards.

A master plan for Ocean Beach

With funding now in place, SPUR has spent the past seven months spearheading the development of a comprehensive interagency master plan for Ocean Beach. We have been working with a consultant team and a wide range of stakeholders to gather information, conduct research and articulate the complex and interconnected challenges facing the city's open coast. This issue of the Urbanist provides an update on the project thus far as we begin to consider solutions.

The Ocean Beach Master Plan is charged with looking at all major aspects of the beach for the next 50 years and beyond. By taking a decidedly long view, developing a consensus vision and working backward to arrive at near- and medium-term actions, the master plan is intended to provide the framework that is missing from short-term decisions today.

The study area encompasses the beach and adjacent lands from the high-water mark to the property line at the eastern edge of the Lower Great Highway and excludes any private property. It takes in 3.5 miles of contiguous coastline from the beach's northern extent to the Fort Funston bluffs. Of course, numerous processes and practices, from transit access to offshore dredging, must be considered as well. The plan will consider Ocean Beach as a whole place: as an urban promenade, a changing coastline, a key segment of the GGNRA, a habitat corridor and a major infrastructure complex. But as much as these aspects are interdependent, the conversation about Ocean Beach invariably returns to the most pressing crisis: the erosion at the south end of the beach and the infrastructure that lies in its path. To plan meaningfully for Ocean Beach as an open space, we must define an approach to coastal management that balances infrastructure needs, natural-resource values and the realities of a changing climate.

Planning for uncertainty on a dynamic coastline

We know that sea levels are rising due to melting polar ice and thermal expansion of the oceans. The State of California projects sea-level rise of 16 inches by 2050 and 55 inches by 2100. The frequency and severity of storms are also likely to increase, and local policymakers have no choice but to adapt. Climate-change adaptation consists of policy and design responses to the negative effects of climate change that have already been "locked in," regardless of how we address carbon emissions going forward. Adaptation will be required in many arenas, from water supply to biodiversity to extreme heat events, but few are as vivid and pressing as sea-level rise.

At Ocean Beach, this means that the sort of erosion episodes that took place in 1997 and 2010 will happen more frequently. As the shoreline recedes, critical wastewater infrastructure along Ocean Beach will face increasing pressure and will need to be protected, reconfigured or abandoned. Natural habitat and recreational amenities are threatened as well. Although we have a pretty clear picture of what will happen as sea levels rise, there is a great deal of uncertainty about its timing and extent.

Ocean Beach is the city's first real test in responding to the effects of climate change. The proximity of critical public infrastructure to the coast throws the challenges into high relief. Where should we hold the coastline? What is the economic value of a beach? A dune system? A threatened bird species? When and how will private property be exposed to coastal hazards?

There are also significant limitations in the available data about the effects of sea-level rise. Existing studies paint a general picture of likely impacts but do not account for local factors like coastal armoring and topography, which will shape coastal processes.

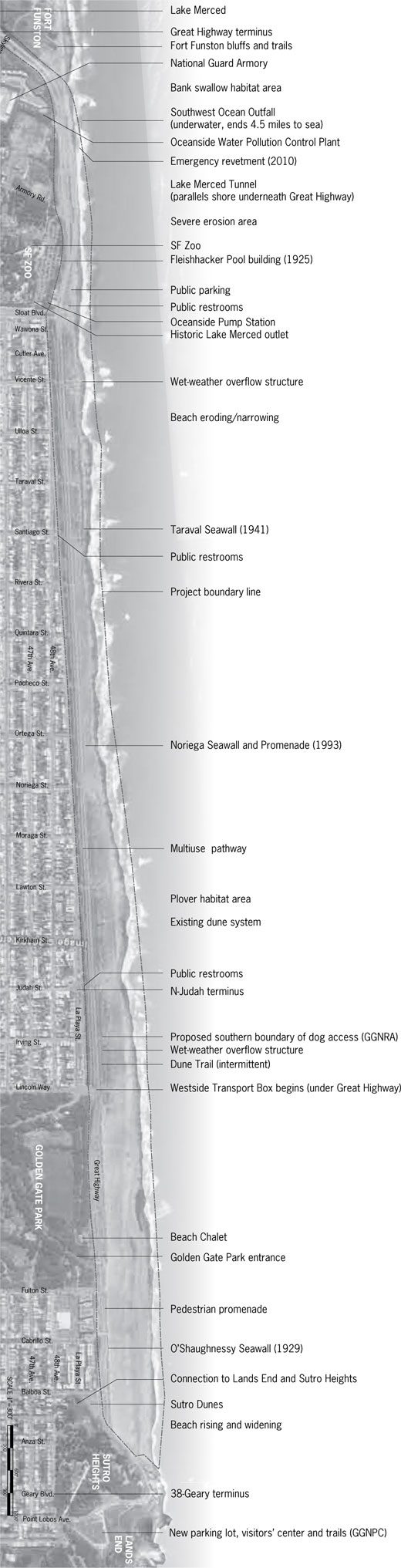

Ocean Beach site overview

Scroll down to see the whole beach.

Planning for a dynamic landscape

Planning for climate-change adaptation sets the complex tradeoffs typical of planning processes against even more complicated new variables: the uncertainties inherent in climate projections.

In this context, planners and designers face new challenges in both space and time. The space itself is changed both by climate impacts and management choices. Even the location of the coastline remains a variable until we have determined where to hold the line and where to retreat. The timing of climate impacts is also uncertain, complicating, for example, the cost comparison of protecting infrastructure versus relocating it. When and how much protection will be required, and how costly will it be? How much of the infrastructure's serviceable life will remain? Discounting and amortizing—tools that economists use to compare costs and benefits over time—become very challenging in a time-uncertain setting.

There are several strategies to address these challenges. First, future adaptation actions can be tied to triggers, rather than dates. These may be physical or spatial (a defined amount of sea-level rise or coastal recession) or fiscal (a defined investment in coastal defenses). Second, planning options are developed not as fixed endpoints but as sequences of actions, each affecting the next and each tied to triggers. Contrast this with a typical design exercise, which may be phased but culminates in a "finished" vision.

At this stage, the Ocean Beach Master Plan has defined seven major focus areas, which we'll examine more closely in the following pages, to organize and distill the project's complex parameters. Although all are important, three have emerged as "drivers" (or form-givers, in design terms) that will establish the context for the others: coastal dynamics, infrastructure and ecology. Over the coming months, the project team will develop scenarios illustrating contrasting approaches to these key areas and the implications of each scenario for Ocean Beach as a whole.

The current dune system at Ocean Beach was constructed in the 1980s and '90s as part of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission's Clean Water Program. It is a non-native system, but it provides habitat, sand stabilization and coastal protection. Photo by Daniel Furon

Process and product

SPUR's nongovernmental status brings both benefits and challenges to the planning process. The Ocean Beach Master Plan will not have the force of regulation. No such plan could, since it addresses federal, state and local agencies. It will live initially as a series of project and policy recommendations from SPUR to the relevant agencies, elected officials and other decision makers. Each agency will have to pursue implementation through its own planning processes, spurred by the momentum and consensus of an effective planning process and the urgency of the situation.

On the positive side, SPUR has the freedom to take a long and broad view. We are less constrained by the highly structured requirements of process and scope faced by public agencies, including the need for immediate environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act or the National Environmental Policy Act. In this case, environmental review will be conducted by individual agencies as they take up implementation actions.

Ecology

Aspiration: Restore and establish conditions that support thriving biological communities

Although Ocean Beach is very much a managed landscape—the alignment of the coast, the shape of the beach and bluffs, and the form and composition of the dunes are all man-made—important biological communities make their homes there. The beach and dune system provide a corridor of scarce habitat for numerous species and connect adjacent parklands.

In particular, there are two threatened bird species at Ocean Beach. The Western Snowy Plover, a federally listed threatened species, inhabits dry back beach, especially in the central part of Ocean Beach. Concerns about the plover have been a factor in a recent proposal by the GGNRA to limit dog access to parts of Ocean Beach. The bank swallow, a state-listed threatened species, inhabits hollows in the exposed bluffs at the south end of Ocean Beach, an especially vulnerable position given the threat of erosion and the installation of coastal armoring.

Both species are protected to some degree by current management practices, including the prohibition of dogs on much of the beach during plover season (July to May) and the cessation of work by San Francisco Department of Public Works (SFDPW) crews during bank swallow season (April to August).

The dune system that predominates from Fulton to Noriega streets (and recurs elsewhere) was primarily constructed as part of the Clean Water Program in the 1980s and helps to protect both wastewater infrastructure and adjacent neighborhoods from coastal hazards. Its morphology and plant communities are both non-native, with iceplant and European dunegrass predominating. The prospect of restoring a native dune system is compelling to many people, although a comprehensive effort would likely be very costly. The master-plan team is examining the implications of such an approach for ecological values, cost, maintenance and coastal hazards.

Ocean Beach is the visible portion of a much larger coastal sediment system. Tides and currents circulate within a U-shaped sandbar called a littoral cell, eroding and depositing sand. The south end of Ocean Beach is outside this cell, and therefore subject to erosion. Source: AECOM and Google Maps

Coastal Dynamics

Aspiration: Identify a proactive approach to coastal management, in the service of desired outcomes

Ocean Beach is the visible portion of a much larger coastal sediment system, the Golden Gate Littoral Cell. The cell is bounded by a large, semicircular sandbar within which sand circulates with the currents and tides. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers annually dredges a ship channel in the sandbar to allow access to the Golden Gate.

The northern end of Ocean Beach has been getting wider since the 1970s due to both sediment management practices (dumping dredged sand within the system rather than in the deep ocean) and natural changes to the sandbars. Meanwhile, the southern end is narrowing as erosive forces scour away sand and bluffs, leaving less buffer between waves and critical infrastructure.

The western shoreline of San Francisco is artificially maintained about 200 feet seaward of its natural equilibrium. Sand was pushed west to create level ground for the construction of the neighborhoods and the Great Highway. The erosion at Ocean Beach is in part a symptom of the coastal processes seeking that equilibrium.

Sea-level rise and accompanying storm surges will significantly worsen erosive pressures at Ocean Beach in the coming years. There are three options for the management of this erosion:

Coastal armoring seeks to resist erosive forces and the receding shore with hard structures such as seawalls or revetments. Depending on its height, a structure might be overtopped by wave runup during storm surges, inundating inland areas. If the coastline recedes until it reaches a hard structure, the beach may be lost. There are nearly 10,000 linear feet of hard structures at Ocean Beach, in the form of the three existing seawalls and recent revetments. This does not including the Westside Transport Box, which could end up functioning as a sort of seawall if exposed by beach and dune recession. Additional armoring is likely south of Sloat Boulevard.

Beach nourishment, or the deliberate placement of sand to counteract erosion, is a promising option at Ocean Beach, since 300,000 cubic yards of dredged sand are available annually. The cost beyond current practices would be shared between local and federal agencies. An effort is underway to retrofit the Essayons, the Army Corps' dredge, to enable it to pump sand directly onto the beach. This could reestablish a wide beach north of Sloat and buy considerable time.

Managed retreat is the gradual reconfiguration or removal of manmade structures in the path of the advancing coastline, according to pre-established triggers. This approach seeks to avoid expending excessive resources defending structures. It is relatively simple to employ where structures like roads or parking lots are concerned, but this strategy would be much more difficult to pursue where expensive, publicly funded sewage-treatment facilities stand in harm's way.

In all likelihood, all of these strategies will be necessary at Ocean Beach. A key objective for the Ocean Beach Master Plan is to analyze the relative needs, costs and locations of various approaches, and build consensus around a compromise.

Infrastructure

Aspiration: Evaluate infrastructure plans and needs in light of uncertain coastal conditions, and pursue a smart, sustainable approach

Beginning in the 1970s, under pressure from the federal Clean Water Act, the SFPUC began to significantly upgrade the city's combined sewerstormwater system, especially on the west side, where the ocean was being subjected to 60 to 70 combined- sewer overflows each year. The SFPUC's Clean Water Program completed the current system in 1993 and has reduced overflows to fewer than eight per year.

The system accomplishes this impressive feat through a series of interconnected components. In dry weather, the west side's wastewater (sewage) runs though the network of local pipes to the Westside Transport Box—a large rectangular tube under the Great Highway—then south to the pump station at Sloat Boulevard. It is pumped to the Oceanside Water Pollution Control Plant, from which secondary-treated effluent is released through the Southwest Ocean Outfall, 4.5 miles out to sea. In wet weather, stormwater runoff surges into the system. When the plant's capacity of 65 million gallons per day is overwhelmed, the transport box and Lake Merced Tunnel—two massive structures designed to store runoff and prevent overflows—fill up and retain the combined flow. Overflow there is decanted to remove solids and pumped to the deep ocean outfall. Only when that system's capacity is exceeded do combined overflows occur, through two large overflow structures on Ocean Beach.

Parts of the Lake Merced Tunnel under the Great Highway south of Sloat Boulevard are immediately vulnerable to erosion. The Westside Transport runs under the Great Highway from Lincoln Boulevard to Sloat Boulevard, and it may become a significant factor in shaping the beach and dunes as the coastline recedes.

Newer thinking at the SFPUC and elsewhere emphasizes low-impact development and green infrastructure—both terms for modifying urban watersheds to increase stormwater retention and infiltration into the ground. Permeable surfaces, green roofs, swales and the restoration of natural waterways can add up to a significant reduction in stormwater entering the combined system.

Wastewater infrastructure is designed for the long haul: Parts of the current system are more than 100 years old. The west-side system is new, expensive and very effective. Unfortunately, it is also exposed to varying degrees of coastal hazard, which we are only recently coming to understand. The Ocean Beach Master Plan is working with the SFPUC to consider how to manage coastal hazards to the infrastructure, including the form and location of coastal armoring, and which components might be reconfigured or moved over time.

A wet-weather overflow structure, one of two at Ocean Beach. Combined-sewer overflows have been reduced from between 60 and 70 per year to fewer than eight a year by the west side's complex of wastewater infrastructure, which is increasingly threatened by erosion. Photo by AECOM

Image and Character

Aspiration: Preserve and celebrate the beach's raw and open beauty while welcoming a broader public.

Although Ocean Beach is in the city, its urban setting is dwarfed by the vastness of the natural context. Like many of San Francisco's best open spaces, it offers a portal to the regional landscape. But both its wild and urban aspects are decidedly less genteel than those of other natural places in the city. The environment—built and natural—shows the elemental scour of wind and waves, and is known for its dense and persistent fog. The local culture has developed an edge that mirrors the environment: Most days, even a stroll on the sand demands a bit of ruggedness, and the surf's frigid rip currents have regularly threatened and even taken lives.

A century ago, Ocean Beach was a very different kind of place, more Coney Island than wilderness. Before the Richmond and Sunset districts took shape, Adolph Sutro's steam railway drew day-trippers through the dunes to his gardens and baths, and to nearby Chutes-at-the-Beach (later Playland). A settlement built of decommissioned horsecars offered a destination for bohemians and bicycle clubs. As the automobile came to prominence, the soft sand was pushed seaward to create a "Great Highway" for Sunday drivers, all the way south to Fleishhacker Pool, near the current site of the San Francisco Zoo. A massive saltwater recreation center built in 1924, the decrepit poolhouse today offers a tempting opportunity for adaptive reuse.

Today, when those few sweet warm days arrive, Ocean Beach again becomes a retreat for the whole city. A festival atmosphere prevails as a crush of cars, bikes and Muni riders descends, and the shortage of services becomes acute as trash piles up, bikes are heaped up and locked together, and dunes become restrooms of last resort.

It would be wrong to ignore the basic needs of the more than 3 million annual visitors to Ocean Beach. But as many in the community have expressed, "prettying up" is not what the beach needs, either. The master-plan team is taking that observation to heart. Good landscape design has the power to strike that balance—to solve problems and serve needs while speaking to the soul of a place.

Our own Coney Island: Ocean Beach offered diverse amusements for day-trippers to the "Outside Lands," including the Sutro Baths and Chutes-at•the-Beach (later Playland, shown here in the 1930s). Image courtesy San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

Program and Uses

Aspiration: Accommodate diverse activities and users, managed for positive coexistence

To be successful, improvements at Ocean Beach will need to accommodate and balance a wide range of users, from surfers to families, birdwatchers to cyclists. For the most part, activities sort themselves into linear zones that can inform the approach to design and programming: joggers and cyclists on the multi-use path, walkers on the dune trails and promenades, anglers on the wet sand and surfers in the water. Basic amenities—such as restrooms, waste collection and food—are in limited supply, and jurisdictional challenges complicate their siting, funding and operation.

As in most open spaces, there are conflicting ideas about which uses belong where, and which are worthy of accommodation. Pedestrians and cyclists get tangled on the multiuse path, birders raise an eyebrow at dog-walkers, and night-time bonfires are a grand tradition to some and a messy nuisance to others.

In January 2011, the National Park Service issued its Draft Dog Management Plan for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. In its preferred alternative, the northern end of Ocean Beach would remain an off-leash area but much of the beach would be entirely off-limits to dogs. Much of that area is already off-limits for nine to 10 months of the year (during plover season), and the GGNRA would remain the only national park to allow dogs at all. Still, the proposal has rankled many dog owners and remains controversial. The National Parks Service is accepting public comment on the draft plan until May 29.

One key challenge is the distinctive pattern of use over time. Most of the time, the beach and promenades are used by relatively few people, many of whom are locals and regular users: walkers and joggers, surfers and cyclists. This "baseline" condition (with its own seasonal and diurnal variations) holds sway until one of those rare hot, sunny weekends, when the beach experiences an enormous spike of visitors from around the region.

Access and Connectivity

Aspiration: Provide seamless and fluid connections to adjacent open spaces, the city and the region

Ocean Beach is not only a destination in itself; it is the connective tissue that links an abundance of open spaces on the city's west side. From Land's End and Sutro Heights at its north end to Golden Gate Park, the Zoo and Fort Funston to the south, Ocean Beach is a key corridor. While movement along Ocean Beach is fairly easy, it offers much weaker connection to adjoining open spaces, neighborhoods and other amenities. In particular, arriving at the beach from Golden Gate Park, which ought to be one of the great landscape experiences in San Francisco, is an anticlimax for pedestrians and cyclists, who are dropped into a sea of asphalt roadway and parking, with little sense of how to proceed. Another significant gap is from Ocean Beach to Fort Funston, the GGNRA's next major park to the south, where pedestrians must walk the highway shoulder and hop the guardrail to access the trails and beach.

Ocean Beach is well-served by the Muni transit system, but while the 38-Geary, N-Judah and L-Taraval lines each terminate within easy walking distance of the beach, the pedestrian connections are weaker than they might be if welcoming transit users were made a priority.

The Great Highway was built in the 1920s as a grand vehicular promenade, the widest stretch of pavement for its length in the world.

Its reconfiguration in the 1990s narrowed it by nearly half, but it remains a traffic artery first and foremost, with a capacity that exceeds its actual usage. South of Sloat Boulevard, the Great Highway is squeezed between the eroding bluffs and inland structures, with traffic capacity to spare.

The City of San Francisco's Sunday Streets program has closed the road to cars a few times, showing us a tantalizing multimodal vision more "great" than "highway." Meanwhile, a campaign by the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition to build a bikeway from San Francisco Bay to the ocean is highlighting Ocean Beach as a major cycling destination with significant shortfalls in connectivity. As our ideas about multimodal streets and recreational waterfront access evolve, it may be time to reevaluate the vehicular emphasis on the city's only oceanfront street.

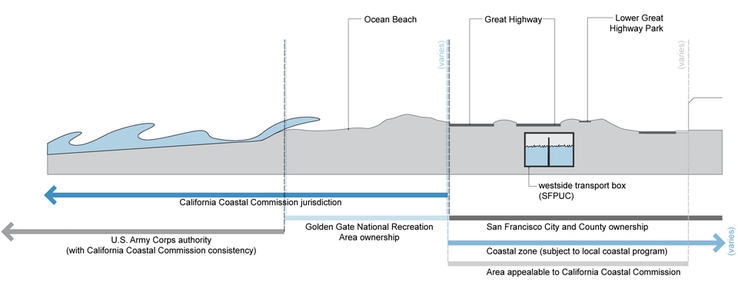

Agency jurisdictions at Ocean Beach

Scroll to see the whole beach.

A basic challenge: Many different agencies oversee aspects of management, planning and permitting at Ocean Beach. Each has its own priorities and internal processes, and no one agency oversees the whole.

Management and Stewardship

Aspiration: Provide an approach to long-term stewardship across agencies, properties and jurisdictions

Although visitors experience Ocean Beach as a whole place, it is administered by an alphabet soup of federal, state and local agencies. The beach, dunes and promenades are mostly federal GGNRA parkland, while the Great Highway, multiuse trail and most parking lots are owned by the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department. The SFDPW provides maintenance and emergency repairs on both city and federal property, while the SFPUC owns and manages underground wastewater infrastructure and the Oceanside Water Pollution Control Plant. Dredging and sediment management by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers shape the beach. The California Coastal Commission is the permitting authority at the beach. Further inland within the coastal zone, the San Francisco Planning Department oversees development decisions through the City's Coastal Commission-approved Local Coastal Program (the Western Shoreline Plan).

With so many agencies involved, it's not hard to understand why problems as simple as managing litter can be challenging—never mind protecting infrastructure while managing a habitat for threatened birds. Not only are these agencies administratively distinct, they often have conflicting priorities as well. For example, National Park Service policies favoring natural resources and processes may conflict with the needs of the SFPUC's infrastructure, although both serve environmental imperatives.

Could Ocean Beach be managed as a single unit? What form would that take? Simply having a consensus vision in place would provide a basis for improved interagency cooperation. A joint operating agreement clearly defining responsibilities, or even the creation of a new management entity or park boundary, could provide the kind of integrated management to see Ocean Beach through the challenges we know are coming.