A disaster of epic proportions is brewing in our backyard. During our lifetime it is probable that we will face a catastrophic earthquake in the urbanized San Francisco Bay Area.

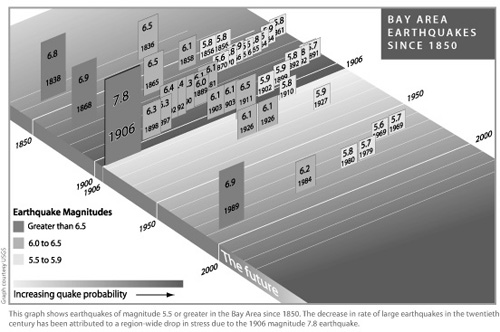

Over the past 75 years, there have only been two earthquakes in the Bay Area with magnitudes of 6.0 or greater. In the preceding 75 years (between 1854 and 1929), there were 16 earthquakes of magnitude 6.0 or stronger, most of which were centered in what are now heavily populated areas. There is little doubt that major earthquakes will hit the Bay Area again, and wreak havoc on our social structure, utilities, transportation, and economy. In San Francisco, our housing stock will suffer the most.

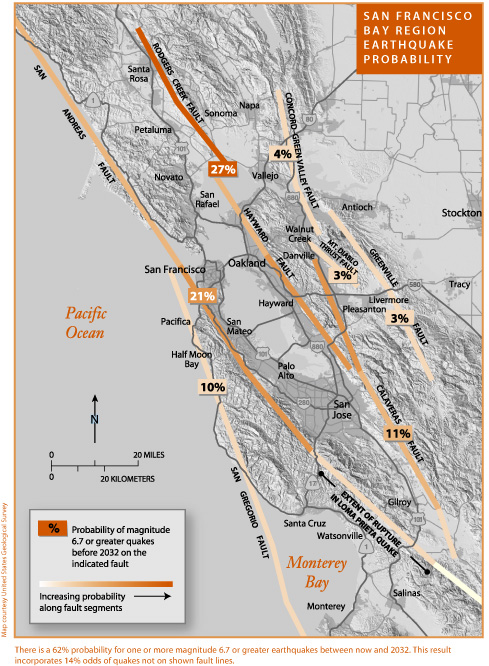

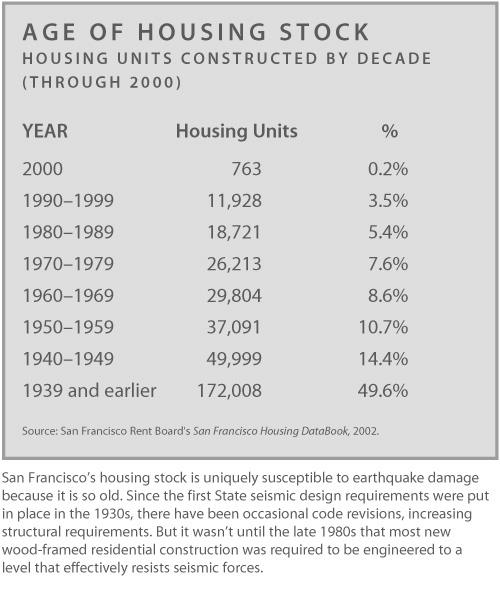

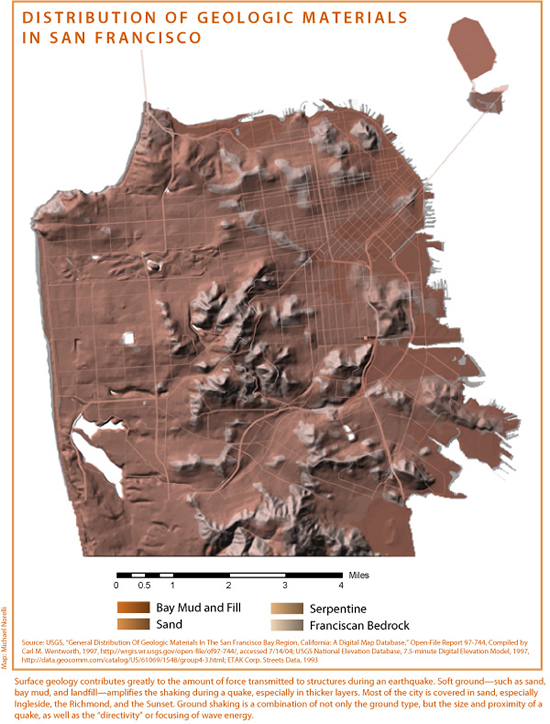

Of all American cities, San Francisco is probably the most vulnerable to catastrophic disaster. Our housing stock is the oldest in the West. Much of the city was built on sand, landfill, and other non-compacted soil, which is subject to liquefaction. And with 75 percent of the rental housing stock covered by rent control, much of the housing stock is poorly maintained. All of these factors exacerbate the dangers inherent to being precariously straddled between the San Andreas and Hayward faults.

When the "Great Earthquake" hit in 1906, San Francisco was the eighth largest city in the United States, and by far the largest city west of the Mississippi. Today, the nine-county Bay Area has a population of nearly seven million. As the population density of the region increases, we become more dependent on an ever-more complex-and fragile-matrix of interrelated infrastructure, social, and economic factors. That template of essential parts is becoming increasingly susceptible to catastrophic failure.

The 1906 Earthquake had an estimated magnitude of 7.8. It, and the fire that followed, caused an estimated 3,000 deaths, $400 million in property damage (in 1906 dollars), and left 250,000 people without shelter.

The economic loss from the next big earthquake to hit the urbanized Bay Area is likely to surpass the ten most expensive disasters in the United States history combined. The real estate and public infrastructure that sit on top of California's major fault zones is valued in the trillions of dollars. Death, suffering, loss, breakdown, and paralysis will be like nothing we have ever seen. In spite of this, the collective actions and policies of our City demonstrates a remarkably blasé attitude in taking action to plan and prepare for future disasters, especially earthquakes.

In 2000, the City's Department of Building Inspection (DBI) initiated a program, known as the Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety (CAPSS), with the mission to develop and implement a work plan for reducing earthquake risks in San Francisco, and to improve post-earthquake response policy. Two and a half years into the project, when its foundational analysis was 80 percent complete, the Building Inspection Commission terminated CAPSS. As a result, CAPSS's essential mandate and work-product was stopped before its benefits could be realized.

The City is at risk, and action needs to be taken to reduce its vulnerability.

What Do We Stand to Lose?

The Bay Area has a long history of seismic activity. Most of these earthquakes occurred in what was then rural areas, before the region exploded to its current population. (The exception, of course, was the Great 1906 Earthquake, which remains the most destructive in the western hemisphere.)

It was not until the 1960s that there was consensus on the theory of plate tectonics (or "continental drift"), or even an understanding of the dynamics of seismoliquefaction. With each new earthquake we gain additional insight into how the region will respond to future seismic events. The relatively small (magnitude 6.4) 1971 San Fernando (Sylmar) earthquake caused damage beyond what anyone had imagined, and resulted in significant revisions to the California Building Code. The 1994 Northridge earthquake and the 1995 Kobe earthquake both occurred in urbanized areas, and provided valuable information (and several surprises) as to how the Bay Area might be affected.

While our understanding of seismic events and their physical effects improves, the matrix of risk factors becomes more complicated. In the last 20 years, the Bay Area has grown from three million to over seven million people. With that growth in population, our reliance on a complex-and tenuous-infrastructure has increased. San Francisco relies on water imported from the Tuolumne River via a system of 280 miles of pipelines, 60 miles of tunnels, and 11 reservoirs. In addition to utilities, Bay Area airports, bridges, and road systems are all vulnerable to fault movement and the liquefaction of unstable soils.

The economic consequences of a major earthquake in this densely populated region is nearly beyond comprehension. Are we prepared for a $100 or $150 billion disaster across the entire Bay Area? To put this in perspective, the recent statewide, $15 billion bond bailout raised widespread concern of its ongoing effects. The Northridge earthquake was the greatest economic disaster in American history, with losses exceeding $25 billion. A year later the Kobe earthquake resulted in a phenomenal $150 billion in property damage. If Loma Prieta had occurred closer to San Francisco, or if a similar-sized earthquake occurs along the densely populated portion of the Hayward fault, similar losses could be expected. The CAPSS study projected that under one disaster scenario the losses to privately owned property in just the city of San Francisco could approach $25 billion. By comparison, the City's budget for 2004-2005 is slightly over $5 billion.

The vast majority of the buildings in San Francisco are residential, and our older housing stock, which exudes the quintessential charm and character of the city, is most vulnerable to failure. It is that risk that poses the greatest threat to our citizens. As long as earthquakes threaten a large percentage of our housing stock, the very essence of our city is in jeopardy.

Modern engineering and evaluation techniques have shown that certain types of building construction are poorly suited to resist the lateral forces caused by earthquakes. Risks to brick unreinforced masonry buildings (UMBs) are well known. However, a number of other building types and characteristics are particularly vulnerable to seismic activity as well, including "soft story"1 buildings, buildings on corner lots, buildings with "cripple walls,"2 buildings on brick foundations, and "non-ductile concrete,"3 buildings. The CAPPS project concluded that wood frame buildings in the Sunset and Richmond (especially corner buildings with soft stories) pose the greatest potential loss in San Francisco.

The city's older, downtown neighborhoods (especially Chinatown, South of Market, the Inner Mission, and the Tenderloin), are expected to suffer disproportionate consequences from future earthquakes-but for other reasons. Together, these neighborhoods provide the bulk of the affordable housing in the city. People who live in these neighborhoods include many who are most at risk if they are made homeless by an earthquake: they are largely low-income, rely heavily on social services, and are less capable of finding alternative housing and support. Today these neighborhoods have the highest population density in the West. And the residential buildings in these neighborhoods are among the oldest, most poorly maintained, and most susceptible to damage from seismic events.

Earthquake-related risks are not limited to damage, injury, or loss of life from the immediate shaking of the ground at the time an earthquake occurs. Other significant risks include the following:

-

Fire. San Francisco's building stock is built primarily of combustible wood. As a result, fires may result in greater damage than the initial earthquake because water lines will be ruptured, and access will be impeded by collapsed buildings and damaged streets. Ninety percent of the building loss in 1906 was due to fire. The truly worst-case scenario is if an earthquake occurs at the end of our annual summer drought, during a period of stiff off-shore winds.

-

Breaks in urban utility supply lines. Beyond water for fire suppression, a major earthquake will likely disrupt domestic water, electricity, natural gas, and telephone services.

-

Loss of economic activity. The city's economic health will be severely affected, including tourism, San Francisco's largest industry. Newer office buildings will likely still be standing, but many workers will be homeless, or unable to reach their jobs because of disruption to the transportation system. To the extent that the economic impacts are long-term, building owners and the government will have reduced financial capacity to undertake rebuilding.

-

Transportation breakdown. San Francisco is particularly vulnerable to transportation problems because we lie at the end of a peninsula, with few access routes over land. Severed transportation routes will have a major impact on the city. BART is particularly vulnerable.

-

Loss of housing, especially affordable housing. In the short run, there will be a tremendous demand for emergency shelters, and we know that the City and State are poorly suited to address those needs. San Francisco will also experience the permanent loss of a substantial portion of its rent-controlled housing.

-

Inundation. Risks from dam failure exist, with a large area in the Sunset being particularly vulnerable. Additional concerns include landslides and mudslides.

-

Regional impacts. A major earthquake will not selectively target San Francisco alone. It will have regional consequences, and San Francisco cannot expect to rely on neighboring communities to supplement the city's needs.

Housing—the Disaster Litmus Test

The regional or neighborhood characteristics of the housing stock, before an earthquake, have a major effect on recovery scenarios. One year after the Loma Prieta earthquake, 90 percent of damaged or destroyed single-family housing had been repaired or replaced. By comparison, after seven years, only 50 percent of destroyed or damaged (uninhabitable) multifamily housing had been repaired or replaced.

Ninety percent of the buildings damaged in the Northridge earthquake (1994) were wood-framed residential structures; the earthquake forced residents in the San Fernando Valley to vacate some 19,000 units (three percent of the housing stock in the San Fernando Valley). However, the Southern California recession resulted in 54,000 units being vacant in the Valley before the earthquake occurred (a nine percent vacancy). As a result, displaced victims quickly found replacement housing in vacant units.

By comparison, San Francisco is famous for its perpetually low vacancy rates.

When a disaster impacts the displaced victims' capacity to find alternative housing, or their capacity to finance repairs, it is truly a major disaster. The terrible firestorms in Oakland (1991) and Malibu (1993) affected affluent populations who were otherwise capable of finding their own replacement housing. Following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, the typical victim in the Marina was young, single, affluent, and mobile. In contrast, the ongoing housing crisis in South of Market, Oakland, Watsonville, and Santa Cruz following the Loma Prieta earthquake resulted in a true, lasting hardship.

San Francisco has approximately 350,000 housing units. Of that total, ABAG projects that 37,600 housing units would be rendered uninhabitable by a magnitude 7.1 earthquake on the Hayward fault; other ABAG scenarios have loss estimates up to 83,000 housing units in San Francisco, depending on the location and severity of the earthquake. These estimates should not be viewed as hyperbole. In San Francisco, the relatively small 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake resulted in 8,600 units becoming uninhabitable (yellow- or red-tagged); and 130 buildings with over 1,000 units were destroyed or irreparably damaged.

It was not until the 1980s that most new residential structures were required to be designed and built to withstand seismic movement. As a result, less than 10 percent of our housing stock has been built to standards which will likely resist significant damage from major earthquakes.

While there has been a great deal of research on the performance of engineered structures (such as steel-frame high rises and concrete parking garages), the same type of analysis is needed to evaluate the potential damage to wood-frame single-family and multifamily structures. One of the many significant benefits of the CAPSS project was that it involved the in-depth analysis of wood-framed residences, necessary to understanding the prevalence of certain building failures, the costs associated with those failures, and the extent to which housing damage will lead to a housing crisis after the disaster. The projected loss of a substantial portion of the building stock in the Richmond and Sunset neighborhoods allows us to develop realistic hazard mitigation and realistic incentives for owners to improve their units before disaster strikes again.

Residential, unreinforced masonry buildings (UMBs) present a different, special set of problems. Residential UMBs are generally rental buildings. The 1992 San Francisco UMB ordinance and Bond Fund are prime case studies of the issues involved. Retrofitting UMBs will result in improved safety. However, many retrofitted UMBs will be irreparably damaged in a major earthquake, and a major source of affordable rental units will be lost.

Whether residential structures are wood-framed or masonry, single- or multi-family, the cost of preventive seismic strengthening is far less than the cost of post-catastrophe loss, repair, and services.

Legislative Actions Implemented to Reduce Risks

The Federal Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (DMA 2000)

DMA 2000 requires State and local communities to have an approved hazard mitigation plan in place by November 2004 in order to be eligible for pre- and post-hazard mitigation grant funds. In the past, Federal legislation has provided funding for disaster relief, recovery, and, in some cases, hazard-mitigation planning. DMA 2000 is the latest legislation intended to improve the state and local planning process, and reinforces the importance of planning for disasters before they occur. The act requires that a pre-disaster hazard mitigation program be approved and adopted before a community can be eligible to receive funds from the Federal post-disaster Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

A community's Disaster Mitigation Plan is expected to comply with guidelines issued by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), including hazard identification and analysis, an analysis of the community's vulnerability and an estimate of potential losses, an assessment of the community's capabilities, and establishing targeted objectives.

In the case of San Francisco, once the Plan is developed, it must then be approved and adopted by the Board of Supervisors. It is then submitted to the State Office of Emergency Services (OES) for review and approval. Following the OES approval, it is submitted to FEMA for final review and approval. Approval by FEMA constitutes formal completion of the plan and establishes San Francisco's eligibility to pursue pre- and post-disaster hazard-mitigation funds.

San Francisco has not allocated the resources necessary to respond to the form or the spirit of the requirements of DMA 2000. While we stand to lose the benefit from future FEMA funds for post-disaster recovery, the act's main purpose (planning and pre-disaster mitigation) is not being addressed. No single person or department is responsible for coordination and preparation of a Plan. Instead, OES, DBI, and the Planning Department are jointly sharing the project. Participants have commented that DMA 2000 mandates a great deal of work without allocating funds to administer the project. An important side benefit of the CAPSS project was that much of the material required for the Plan was being prepared, separately, as part of CAPSS.

State Guidelines

In 1986 the State passed SB 547 (the "Unreinforced Masonry Law") to address concerns surrounding earthquake dangers. Beyond mandatory inventory and notification requirements, SB 547 requires each jurisdiction in California's Seismic Hazard Zone 4 (generally, our seismically active coastal zone) to develop a mitigation program to reduce unreinforced masonry hazards. Seismic Hazard Zone 4 includes the major metropolitan areas of the Bay Area and the Los Angeles Basin, where roughly 28 million people (or 75 percent of the state's population) live. Significantly, the law exempts residential buildings of five units or less, and any building which qualifies as "historic" property.

Approximately 25,400 unreinforced masonry buildings (UMBs) have been inventoried in Zone 4's 366 jurisdictions. While this is a relatively small percentage of the state's 12 million buildings, it represents a significant proportion of the rent controlled and low-income housing stock in parts of San Francisco.

The State adopted suggested minimum standards ("Special" and "General" procedures) to which UMBs should be strengthened, as designated in the 2001 California Building Standards Code. By contrast, newly constructed buildings are designed to a much higher, "life safety" standard.

San Francisco's Programs

The UMB Ordinance: A Dangerous Failure to Communicate

In response to the State's mandate, San Francisco passed the UMB ordinance in 1992. The "non-exempt" buildings were characterized under one of four designated risk levels, with a corresponding time table for seismic retrofitting. Of the total 2,068 UMBs, 424 are either exempt from mandatory retrofitting, or have been demolished.

One shortcoming of the UMB ordinance is that it exempts hundreds of buildings from the mandatory retrofitting requirements, including residential buildings of four or fewer residential units. It is dangerous to exclude small residential buildings from the requirements, since they make up a large percentage of the total number of housing units.

Unfortunately, few UMB (retrofitted or not) are likely to be habitable after a significant earthquake. Building owners and occupants need to understand this critical shortcoming of masonry construction.

The Seismic Safety Loan Program (the "Bond Program")

As a condition of imposing mandatory retrofitting requirements on the owners of UMBs, the City gained voter approval for a $350 million bond program, which made financing available for retrofitting UMBs. A major element of the program was that it would provide financial resources for both market-rate and subsidized rental programs, according to an established allocation. Ten percent, or $35 million, of the funds would be available each year, of which $20 million would be available for market-rate projects (which include privately owned, rent controlled properties), while the remaining $15 million was available for buildings housing low income tenants (at below-market financing of 21/2 percent).

Unfortunately, very few owners of market-rate buildings have used money from the bond program: if every project currently in the pipeline gains funding, less than $8 million of the $350 million total authorized bond will have been used by market-rate projects since the project was initiated in 1994. Potential private-sector borrowers found that the program came with too many conditions and restrictions, which provided too many financial and procedural disincentives to make it feasible.5 In short, the bond program has failed in its goal to facilitate the seismic strengthening of privately owned UMBs, although it has been useful as a funding source for some affordable housing upgrades.

CAPSS—a Brief History

In 2000, DBI initiated a new program known as the Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety (CAPSS). CAPSS's purpose, among other things, was to develop and implement a work plan for reducing earthquake risks in San Francisco, and to improve post-earthquake response policy.

CAPSS was divided into three phases:

Phase I was completed in late 2000, and was an effort by DBI to develop a detailed workplan to evaluate the seismic risks facing the community, and to recommend feasible and practical measures to reduce those risks.

Phase II had three elements, with the following stated objectives:

Task 1: Prepare an impact assessment that develops estimates of the impacts on lives, housing, and the San Francisco economy, based upon a set of likely earthquake scenarios

Task 2: Formulate earthquake repair criteria

Task 3: Identify activities that would reduce seismic risks in San Francisco

Phase III was intended to implement the recommendations of Task 3.

CAPSS was funded entirely by non-General Fund monies. One source of funds available for the project was the Strong Motion Instrumentation Program fee (SMIP) fund, an assessment on building permits. The majority is sent to the State, but a five percent portion is retained by each jurisdiction for appropriate earthquake programs, such as CAPSS. A large amount of untapped money is still available in San Francisco's SMIP fund.

CAPSS's mandate was to address the effect of seismic events on all privately owned property in San Francisco. It was not within the scope of the project to address governmentally owned structures or the effect on hospitals, schools, the San Francisco International Airport, or infrastructure (such as roads and water systems). These limitations were deliberately made to control the scope (and cost) of a very broad project.

The lead contractor on the CAPSS project was the Applied Technology Council, a non-profit organization. A large group of volunteers (the majority of whom were SPUR members) were brought together as a Project Advisory Committee to oversee the direction of CAPSS. Further, a blue-ribbon committee of volunteer structural engineers monitored the technical process, assumptions, and conclusions. The volunteer committees met often and were unified in their purpose of seeing CAPSS fulfill its purpose to plan for, and mitigate the effects of future earthquakes in San Francisco.

As mentioned previously, in the Spring of 2003, the Building Inspection Commission was pressured to terminate CAPSS, by eliminating its funding. As a result, the CAPSS project was stopped before the essential work product (recommending specific action to be taken) could be produced and submitted to the City's legislative bodies. Many factors contributed to the termination of the CAPSS project, including political maneuvering and pressure from the Residential Builders' Association, the bungling of other consultants' work, and the substantial misallocation of resources in the computer scandal. All of these factors, however, were extraneous to the high quality of work and public purpose of the CAPSS team. The program was expertly administrated for the City by Chief Building Inspector Laurence Kornfield.

The total effect further demonstrates the dysfunction of the Department of Building Inspection, and why the important projects of disaster preparedness should be moved to another arena (I suggest that the Mayor's Office is the appropriate venue) which is better able to make the public interest and safety its paramount concern.

CAPSS was gaining nationwide attention and respect as an ambitious and effective project. As far as it got, CAPSS was incredibly successful in devising an innovative, comprehensive evaluation of impacts which would result from a major earthquake.

CAPSS made the following preliminary conclusions:

- The Mission, Downtown (including SOMA) and the Sunset districts would sustain the highest number of lost units. Soft stories would account for most building damage; corner buildings are most at risk

- Depending on the location and magnitude of the event, San Francisco could lose between 8 and 29 percent of its building stock

- One and two family homes will account for between 4 and 38 percent of the direct dollar losses

- Depending on weather, post-earthquake fires could increase losses by 20 to 50 percent

- A major earthquake will have a significant fiscal impact on San Francisco

- Impacts vary enormously from earthquake to earthquake

Approximately $438,000 had been billed for the work done on Phase II, when the project was terminated. But everyone who worked on the CAPSS project acknowledged that the vulnerability study and other preliminary work was never intended to be the critical product or result of the CAPSS project. Rather, mandates and incentives for the structural upgrading to the most-susceptible structures, and standards for post-earthquake repairs (which involve code revisions) are the critical components of the project. It was certainly necessary to expend the substantial time and money going through the process of Phases I and II, in order to secure a foundation for the actions which were to be recommended in Phase III. It is that final part of the project, Phase III, which would actually save lives, reduce property damage, and mitigate the many other effects of future earthquakes.6

Rent Control—the Third Rail

It is a cruel reality that rent-controlled structures comprise the oldest portion of the city's housing stock, which also constitutes the buildings that are most susceptible to damage or destruction from seismic activity. As a result, rent control issues are an important element when talking about earthquake preparedness, and the following three issues are examples of the inherent problems.

1. There is an important debate about who should pay the price to retrofit older rent-controlled buildings. Presently, only a limited amount of retrofit costs are allowed to be passed along to tenants. The predictable result is that much discretionary work to seismically strengthen residential structures will not get done.

2. If rent-controlled structures are destroyed, or are damaged beyond repair and are subsequently demolished, replacement structures will be exempt from rent control. (San Francisco's Rent Stabilization Ordinance exempts buildings built after June, 1979; State law exempts buildings built after February, 1995 from any local rent control.) Such structures are likely to be redeveloped as owner-occupied structures, rather than rental properties, shifting the balance of housing from (supposedly affordable) rental units to newly constructed, owner-occupied structures. But even if the new units are rental, they will not be under rent control.

3. In some cases, damaged (but not destroyed) rent-controlled units may not have the cash flow (or other financial incentive) to allow the owners to make repairs. The possible effect is that there will be a further degradation of the city's affordable housing stock, and the possible abandonment (and ultimate demolition) of low-income housing.

An Ounce of Prevention

There are many additional technical, economic, social, and urban-context issues that surround San Francisco's seismic mitigation, retrofit, and readiness policies. These need to be addressed against the background of two dominant factors: residential buildings will suffer the greatest damage, and their loss and damage will cause the greatest hardship on San Francisco.

While residents in disaster-prone areas take false comfort in the apparent availability of public and private funds (insurance) to speed disaster recovery, the financial community and the federal government are looking for ways to reduce their obligations to fund disaster-recovery costs. States and local governments are caught in-between. Certainly, San Francisco and the rest of California are ill prepared to fund a mega-billion-dollar relief effort.

Faced with the reality of certain future catastrophes and reduced support from government relief funds and private insurance, we need to adopt strategies that lead to loss prevention, and strike a balance between public and private responsibility for funding recovery. The debate can be distilled down to politically difficult questions involving the level (and price) of structural retrofitting that government should impose on property owners. Should that formula be different for single-family dwellings and multifamily structures? How much public value should be put on rent-controlled buildings, where the benefit of below-market rents has become an accepted part of our local picture, yet where its fact may impede the financial feasibility of making repairs?

How safe is safe enough? The higher costs associated with higher protection will meet with fierce objections from building owners (particularly owners of investment properties), who may, in some situations choose to abandon their properties rather than make mandated improvements.

Additional issues arise with regards to UMBs since the fact remains that, by their very nature, they are brittle structures, and seismic retrofitting will not eliminate their vulnerability to damage. The 1994 Northridge earthquake demonstrated this fact when some retrofitted UMBs were still damaged beyond hope of repair, and needed to be demolished. Property owners and communities who do not understand the objectives of retrofitting (reducing personal injury and loss of life), and the corresponding shortcomings, will be disappointed.

We have placed a high value on the continuance of privately owned affordable housing, as evidenced by the prominence of the rent control ordinance, but we have enacted a hodgepodge of regulations, programs, and policies that provide disincentives for owners to structurally upgrade rental housing.

The debate can be further divided between larger (predominantly rental) structures, which are generally covered by rent control, and smaller (predominantly owner-occupied) structures, such as the Sunset houses identified in the CAPSS assessment study as being very susceptible to major damage. The solution is to craft the right combination of mandates and incentives to motivate all property owners to make structural improvements.

The City of Berkeley has taken an unusually aggressive stance towards disaster preparedness, which might provide useful guidelines for San Francisco. In an effort to address seismic safety, Berkeley charges a real estate transfer tax of 1.5 percent of the sales price of residential property; the tax is applied at the time a property is sold. If a property has met seismic retrofitting standards, or if upgrading work is performed within a year of the property's transfer, the owner can apply for exemption or refund, as appropriate.

Regardless of whether the buildings impacted in future earthquakes are single-family or multifamily structures, we know that many people will be left without shelter; returning people to their permanent residences—if safety can be assured—in the shortest period of time is an important goal. However, present code guidelines need to be changed to accommodate disaster situations, where society's objectives are different than in non-disaster situations.

Where Do We Go From Here?

While we sit in one of the most seismically active regions, we also have some of the best resources to confront seismic risks. We are blessed with the most respected community of seismic experts in the world. We also have the experience gained from other catastrophic events — earthquakes and hurricanes, urban and rural, in developed and undeveloped countries.

The knowledge exists to significantly improve structures' capacity to resist earthquake damage, which can result in the corresponding reduction in deaths, injuries and financial loss. What is lacking is a consistent willingness to marshal the resources necessary to make changes that will significantly reduce the impact of future earthquakes.

We need to revisit our policies relative to reducing earthquake, and other disaster-related hazards in San Francisco. Specifically, I recommend the following:

1. The Mayor's Office should oversee disaster preparedness, and assume the responsibility of completing CAPSS and DMA 2000. There is nothing San Francisco can do that is more important than disaster preparedness. Impediments to this essential task (political bickering, departmental fiefdoms, budgetary considerations, and the like) need to be recognized and resolved so the essential task of disaster preparedness can be pursued.

2. CAPSS should be reestablished, and itsoriginal purpose should be brought to fruition. The substantial amount of money spent on the vulnerability study will be wasted if it is not tied into a set of specific recommendations that are subsequently implemented. These recommendations would be adopted in the form of proposed code changes, to be presented to the Board of Supervisors. Studies have never changed lives. But action resulting from careful, scientific analysis of data can have a dramatically positive effect on our ability to weather future earthquakes.

3. CAPSS had a finite, focused purpose. Many areas of expected impact were purposefully not explored in the CAPSS vulnerability analysis, but will, nonetheless, have a profound impact on our city following a major earthquake. CAPSS should identify future impacts that are outside of its purview, but that are likely to have the greatest impact on the city, and merit future analysis and planning.

4. Voluntary maintenance, repair, and seismic upgrading will reduce the risk of damage to San Francisco's housing stock. However, governmental policies (including zoning, demolition, and rent control) discourage maintenance, repair, and structural strengthening (beyond that mandated by law); and rewards property owners whose buildings must be demolished as a result of a catastrophic event. Conflicts exist between the objectives of strengthening buildings and making the housing stock less vulnerable to damage and destruction, and provisions in the rent control ordinance that provide disincentives to property owners. City government should identify these conflicts, and seek a means to resolve the conflicts.

5. Society as a whole benefits from the continuity of a community's social fabric. In San Francisco, the loss of architecturally significant buildings, our diverse population, or local neighborhood-serving retail would diminish the qualities we all value. However, we have not assumed the appropriate share of the costs required to reduce the risk of loss of these socially valuable elements. The City should confront these issues by providing financial assistance and affirmative incentives (such as Berkeley's) to encourage the seismic strengthening of susceptible buildings.

6. In San Francisco, we have also put a high social value on privately owned, rent-controlled housing. However, if society relies primarily on private funding to implement the programs, there is an irreconcilable conflict between the policies meant to implement the relatively short term goals of rent control, and the long-term objectives of seismic safety. The Board of Supervisors should evaluate changes to the Planning and Building Codes and the Rent Control Ordinance that increase incentives for property owners to perform voluntary repair, maintenance, and structural upgrading.

Assuming that the City does not change its policy with regards to either of these two objectives, the conflict between them should be resolved through public funding, which would supplement private funds, and enhance the minimum safety standards for existing rent-controlled buildings.

7. Small residential buildings (four units and less) are exempt from the UMB ordinance. However, small residential buildings are not exempt from seismic risks, especially those with soft fronts, tall cripple walls, and lacking adequate foundation bolting. Future policies and incentives should encourage structural upgrading of these buildingsas well as larger structures.

8. San Francisco has not allocated the resources necessary to address the Federal Disaster Mitigation Act. The act's requirements should not be viewed as a burden, but rather as an opportunity for us to carefully evaluate—and plan for—our known high level of vulnerability to earthquakes and the resulting fires. A plan of action should be put in place, allocating specific responsibility for meeting the letter and spirit of the act, and adequate funding should be provided to meet the important procedural requirements.

The degree to which we in San Francisco—our leaders, our financial communities, and our citizens—are prepared to cope with future urban disasters depends on our collective resolve to undertake effective pre-disaster mitigation programs and our capacity to understand locally specific factors that affect post-disaster recovery policies. We have been living on borrowed time, and our continued failure to prepare for impending disasters will severely impact us. The CAPSS program was an extraordinary step in the right direction; its original purpose should be brought to fruition, and used as a foundation to seek a comprehensive pre-disaster plan.

The author wishes to acknowledge that much of the material in this paper was taken from two recent books that discuss earthquake vulnerability, Disaster Hits Home, by Mary Comerio; and A Dangerous Place, by Marc Reisner. The author also wants to acknowledge and thank the many people who added to this project, including Bruce Bonacker, Pat Buscovich, Mary Comerio, David Prowler, George Williams, and Mary Lou Zoback.