The Port of Oakland is part of an economic ecosystem that supports 73,000 middle-wage jobs throughout Northern California. [1] These are jobs in industries like transportation, logistics, warehousing and wholesale trade. They are middle-class jobs: well-compensated, skilled-labor positions that don’t require an advanced degree — a type that is increasingly disappearing from the region.

Beyond the jobs that are a part of its core businesses, the Port is an anchor for the East Bay’s broader industrial ecosystem, which ranges from manufacturing businesses to wholesalers, storage and recycling companies to luxury importers, industrial artists and makers. The Port’s presence supports other industries, bringing in goods used by Bay Area companies and allowing these industries and others (such as Central Valley agriculture) to export their products to global markets. The existence of a working industrial Port plays an important role in conversations about inclusive economic opportunity in the Bay Area. But this engine of jobs faces some big challenges, ranging from significant debt pressure to rising competition from other ports in North America. Its long-term presence in the Bay Area is not assured.

For those concerned, as SPUR is, about the region’s overall economic competitiveness and the availability of middle-wage jobs, it is essential to understand the complicated infrastructure and policy agenda that the Port of Oakland has to navigate.

Defining the Port

At 5,000 acres of land and 10,000 acres of water, the Port of Oakland occupies 19 miles — almost the entire extent — of the Oakland waterfront, stretching from the Bay Bridge in the north to San Leandro in the south.

While many hear the word “port” and think of ships and the iconic cranes of the maritime port, the Port of Oakland in fact comprises three different lines of business: a 1,300 acre seaport, an international airport and a real-estate operation with nearly 840 acres of office, retail, hotels and parks. [2] Together the maritime, aviation and commercial real estate enterprises of the Port have an operating budget of $314 million annually. [3] The Port and its partners support nearly 29,000 direct jobs, more than half of them in Alameda County.

Since 1927 when it was formally incorporated, the Port of Oakland has existed nominally within, but functionally independent of, local government. The Oakland mayor nominates commissioners, and the Oakland City Council appoints them. Once appointed, the Oakland Board of Port Commissioners makes policy decisions on how to run the Port, and Port staff operates and manages the Port.

As an enterprise agency, the Port of Oakland has its own budget and is charged with generating the revenue to sustain its own operations. Though this belies a complex fiscal relationship between the Port and local governments. The Port doesn’t receive local tax dollars, but it does count on local, state and federal grants for major capital projects, a key fact for a capital-intensive industry. The Port contributes to local coffers in payments for the services it requires — police, fire, water, etc. — and the economic activity of the Port and its partners generates hundreds of millions in state and local taxes.

In practical terms, the Port of Oakland is a landlord port, maintaining, leasing and providing some facility services to tenant operators for a range of economic activities. Tenants of the Port include shipping lines and airlines, terminal operators, aircraft maintenance, logistics and exporting and importing businesses and other companies that do business on the Port’s land. This in contrast to ports that actually operate their own terminals and hire their own dockworkers. [The major ports of the south Atlantic region (in Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia), all have an operating port model.]

As a landlord, the Port of Oakland competes with other ports for its business. For example, shipping companies can choose to go to Los Angeles or Long Beach, California, Seattle or Tacoma, Washington or Prince Rupert, in British Columbia; airlines can choose to fly in and out of other Northern California airports like Sacramento or San Francisco; and office tenants and retailers can choose to locate in downtown San Francisco or Emeryville instead of the Port’s Jack London Square. The Port succeeds by investing its revenue in maintaining the competitiveness of its three distinct lines of business.

The public benefits from the success of the Port by having a high-quality airport and a maritime port that provide thousands of good jobs and support a broader ecosystem of industries. The Port also has a role as a state lands trustee to oversee more than 630 acres of public access and open space, including property along the Oakland waterfront. A successful port has more revenues to invest in public benefits ranging from a high–quality waterfront to better airport terminals.

Oakland’s Waterfront: A Brief History

A working harbor in Oakland has existed in some form since the Gold Rush, which transformed San Francisco Bay into a major hub of maritime activity. Early monopolies over the waterfront land — first by one of Oakland’s mayors, and then by railroad interests — limited growth of a municipal port through the 19th century. During this time, Oakland became the terminus of the transcontinental railroad and the Port of San Francisco continued to dominate the Bay shipping trade, with an elaborate ferryboat system to deliver goods from the East Bay to ships docked in San Francisco.

Over the decades, major public works projects transformed the marshy Oakland shoreline into a deep-water, industrial harbor. Oakland and Alameda residents invested in their waterfront, voting on several major annexations and bond issues. In 1924, Oakland voters approved an amendment to their City Charter, bringing all city-owned shoreline properties under the jurisdiction of a new, independent arm of government — the Port of Oakland, which was formally established in 1927. Construction of the Oakland Airport began the same year. Oakland had one of the first and best known municipal airports in the country.

The World Wars stimulated growth in the port. In 1941, within days of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Oakland Army Base and Naval Base were created on hundreds of acres of former tideland, the airport was brought under military control and the Port of Oakland became one of the nation’s busiest military ports.

Equally important to the shape of the modern maritime port were postwar developments, in particular containerization and the growth of the airport.

Containerization refers to the practice of standardizing shipping through use of steel/aluminum boxes. The practice began in its modern form in the 1950s and spread rapidly. The uniform containers could be packed with a broad array of goods and easily stacked and transferred between multiple transportation modes — from atop a railcar to a ship to a truck. The new system offered many advantages including cost savings through greater efficiency and security in the movement of goods. The “container revolution” is credited with a massive expansion in international trade — even with globalization in general. It has also dramatically changed the demands on port infrastructure and labor. The tension between labor and technology is an ongoing point of debate, change and compromise at the port to this day.

Its hulking cranes and containers are the visual hallmarks of the Port, making it easy to forget that the airport is a key component. In fact, Oakland International is the number one cargo airport in the Bay Area. Photo courtesy Port of Oakland.

Its hulking cranes and containers are the visual hallmarks of the Port, making it easy to forget that the airport is a key component. In fact, Oakland International is the number one cargo airport in the Bay Area. Photo courtesy Port of Oakland.

The advent of containerization was one of the key factors that lead to the Port of Oakland supplanting the Port of San Francisco as the primary port for the Bay Area. In the 1960s the Port of Oakland became the first major port on the West Coast to build terminals for container ships and invest in landside container cranes. Oakland already had the better rail connections. And the greater availability of adjacent backlands for stacking containers in Oakland, coupled with Oakland’s pioneering and San Francisco’s late investment in containerization, helped seal the end of San Francisco’s port as a cargo operation. Today, the Port of Oakland handles 99 percent of the containerized goods that enter and leave the region.

Concurrent with the era of containerization was the growth of commercial aviation. Oakland Airport opened its first jet age terminal in 1962 (Terminal 1) and a second terminal in 1985 and now, Oakland International Airport is one of three major commercial airports serving the Bay Area with daily passenger and cargo flights. Air cargo has been an important part of the airport’s growth and job creation strategy. Oakland International is the number one cargo airport in the Bay Area (by volume), and its leading cargo carriers are some of the East Bay’s significant employers – including UPS (United Postal Service) and FedEx – whose West Coast Asia Pacific operations are based here.

The airport is now the largest single part of the Port of Oakland — by revenue and by jobs impact, and it is the part that is growing fastest. Four of the Port’s five biggest capital projects today are airport investments including the just-completed BART Connector between the Coliseum and Oakland Airport stations. The airport is a key aspect of the Port’s vision for the future.

An Asset With Challenges

The Port of Oakland is charged with several major responsibilities: sustaining its public interest enterprises, managing state tidelands and serving as an engine for local economic development. But this economic anchor faces huge challenges. The biggest immediate challenge is fiscal. In the early 2000s, the Port of Oakland borrowed more than $1.4 billion, and it still has 18 years remaining on its repayment schedule. Its debt service payment is more than $100 million annually, nearly a third of its operating budget.

Port Jurisdiction

The Port of Oakland’s jurisdiction extends along 19 miles of East Bay waterfront and includes seaport, airport and commercial real estate areas as well as public parks and open space. The Port must continually maintain and upgrade its facilities to accommodate future growth, improve competitiveness, enhance security, and support public access and environmental stewardship of the waterfront. Source: Port of Oakland.

But the trouble goes deeper. In essence, the Port borrowed money to invest in its facilities (particularly the investments required to get “big-ship ready”), but it doesn’t have enough business to pay back the debt. Underlying this problem is the fact that the Port of Oakland’s seaport — which powers 40 percent of port-connected jobs and 44 percent of its revenue — is losing market share to other ports. Since 2006, the Port’s container volume has plateaued. International trade may be expanding, but most of the business is going elsewhere.

Essentially, Oakland has lost the size wars to Southern California’s maritime ports. L.A. and Long Beach together handle seven times more cargo volume than Oakland. These ports have benefitted from economies of scale and better rail connections to Midwestern and Eastern markets. L.A. and Long Beach have an intrinsic advantage in having 20 million customers within 100 miles, while the Port of Oakland has less than half the customer base. The nation’s railroads have invested heavily in access to L.A. and Long Beach, with negligible new investments for Oakland or the Pacific Northwest. The competition from Southern California is so intense that the ports there are able to generate substantial funds to make the infrastructure investments necessary to more efficiently move cargo. (On the other hand, they are so full that, at least in the near term, Oakland benefits from their spillover.)

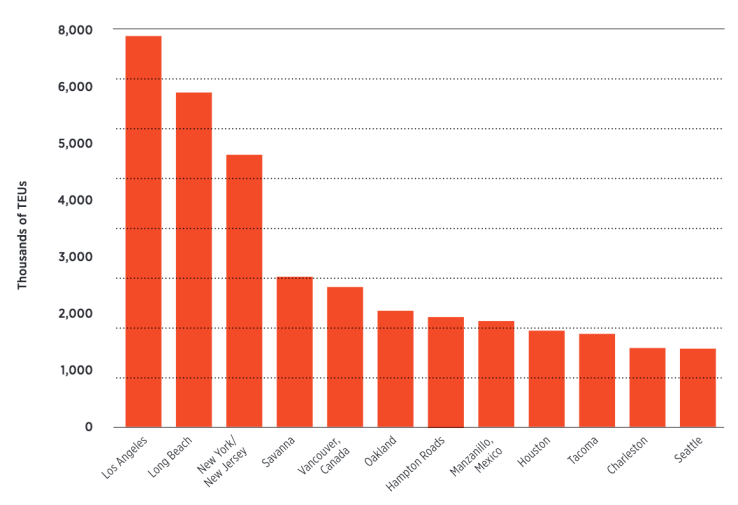

Annual Volume of Major North American Container Ports

The Port of Oakland is the fifth busiest container port in the United States. It faces stiff competition from other North American ports. Source: American Association of Port Authorities, NAFTA Region Container Traffic 2013 Port Rankings by TEU.

The way shippers make their choices is basically based on speed, cost and reliability in connecting suppliers and customers. Ocean connections to Oakland have become longer as manufacturing and consumption in Asia have shifted south from Japan and Korea to China and Southeast Asia. With U.S. consumption still centered in the Midwest and East, Oakland also has longer connections to the rest of America than many of its competitor ports. The costs of piloting ships is more expensive in San Francisco Bay than elsewhere, the longshore labor force is aging and losing productivity and California has some of the most progressive and effective (but also costly) environmental regulations in the world for shippers. Labor/management disputes at all West Coast ports and community unrest at the Port of Oakland — like that seen early this year — have affected shippers’ sense of the Port’s reliability. Shippers frustrated by delays in Oakland and elsewhere in California have other gateways: Mexican and Canadian ports, Suez and Panama Canal routes to the East Coast.

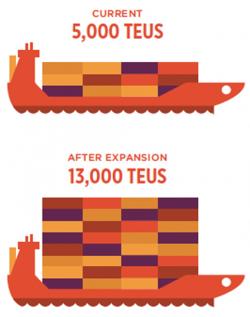

In the longer run, a looming question is how the widening of the Panama Canal will affect ports. The $5.3 billion Panama Canal expansion project, scheduled for completion this year, will double the capacity of the canal and allow for ships of nearly three times the current maximum size to pass through. Whereas before, big ships crossing the Pacific from Asia have had to count on unloading at West Coast ports, they will now have the ability to transit the canal and offload closer to the population (and customer) centers of the United States. On the other hand, trans-Atlantic shippers could also use the same route to bypass East and Gulf Coast ports, in which case, Oakland could benefit from more trade from Europe.

The jury is still out on the impacts of the Panama Canal’s expansion, but it is a concern at all U.S. ports. Together, sixty-three North American ports are planning to invest $46 billion for infrastructure in the five years from 2012 to 2016, compared with a combined $30.1 billion spent in the entire 60-year period from 1946 through 2005. [4]

Ship Size Limit at Panama Canal in TEUs*

Scheduled for completion in 2015, the $5.3 billion Panama Canal expansion project will double the capacity of the canal and allow for ships of nearly three times the current maximum size to pass through. Source: Colliers International, “North American Port Analysis.” December 2013.

* A “twenty-foot equivalent" unit (TEU) is the standard unit for measuring cargo capacity in shipping. The dimensions of a TEU are 20 by 8 by 9 feet.

Another major issue facing all U.S. ports is automation (using robotics such as automated transport vehicles, automated stacking cranes, and the like to perform jobs historically done by people). Automated port operation started in Europe in the 1990s, made it to the U.S. in 2007, and is being deployed now in Los Angeles, Long Beach and New Jersey. The Port of Oakland recently consolidated its facilities into larger terminals, which provides an opportunity for adopting automation here. But the capital cost will be high, Oakland’s weak competitive position deters investment by its tenants and port labor is highly resistant. If automation spreads before Oakland can regain its footing, the Port’s competitiveness may be further eroded.

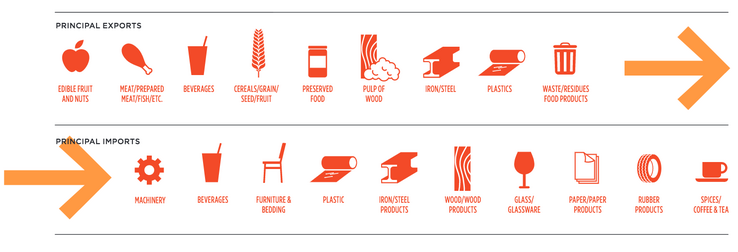

The Port of Oakland Top 10 Commodities by Tonnage (Containerized)

The largest import are beverages, furniture and glassware; the largest exports are wood pulp, edible fruit and nuts, and meat. Source: U.S. Dept of Commerce, Bureau of Census.

The largest import are beverages, furniture and glassware; the largest exports are wood pulp, edible fruit and nuts, and meat. Source: U.S. Dept of Commerce, Bureau of Census.

The strategic investments the Port is currently making are geared toward creating a new advantage in this competitive landscape. The most important of these investments is taking place at the former Oakland Army Base, which is in the process of being transformed into a premier logistics center. The Port is developing its share of the 360-acre former Oakland Army Base with industry-leading rail, warehousing and loading facilities. The goal is to offer the customers whose business the Port is competing for — big retailers, agribusinesses and manufacturers — a compelling reason for using the Port of Oakland. The idea is to create the capacity to provide key services on-site, such as trans-loading (moving goods from one set of transport units to another), warehousing and state-of-the-art cold storage services on-site. Oakland will be one of the few gateways that will have those kinds of amenities inside the port footprint. Shippers will have the opportunity to get several service needs met within the Oakland seaport and reduce their costs.

Looking Forward

The Bay Area came into modern-day success as a manufacturing and industrial region. And from the export of gold to the dissemination of the semiconductor, to the distribution of almonds and cabernet, the Port of Oakland has been central to the region’s success. One of the most exportfocused ports in the country, Oakland makes the Bay Area not just the portal for ideas, but the physical gateway where the enormous, diverse Northern California economy sends its goods to the rest of the world.

The industrial legacy and future of the region, and the future of the diverse ecosystem of companies and good-paying jobs supported by the Port’s presence depend on the resolution of major questions:

- How will shifts in global trade impact the Port of Oakland?

- How will the Port resolve its fiscal challenges?

- What resources will the Port have to bring to its multiple roles as a global commercial gateway, economic development driver and landlord at the center of this dynamic region?

- To what extent will the Port continue to provide and support middle-wage jobs that help people move up the income ladder?

- Can the Port balance the need to run safer and cleaner using new technology, with the need to protect worker interests?

Answering these questions is important for Oakland, the East Bay and the broader region.

Endnotes

[1] Port of Oakland, “Powering Jobs, Empowering Communities,” portofoakland.com/pdf/about/JobsBrochure.pdf

[2] Port of Oakland, FY 2016 DRAFT Budget Book Summary.

[3] Port of Oakland, FY 2015 Budget Book.

[4] Bloomberg Business, “Investors Punish Miami Port Tripling Debt to Expand.” September 2013. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-09-10/investors-punish-miami-port-tripling-debt-to-expand-muni-credit