After the Embarcadero and Central freeways were severely damaged in the Loma Prieta earthquake, San Francisco took a tragic situation and turned it into a great urban planning success story: the creation of the Embarcadero and Octavia boulevards. Taking down these freeways and replacing them with surface boulevards created enormous positive land use changes in the surrounding neighborhoods. This enabled San Francisco to reconnect with its waterfront and supported the creation of the Market and Octavia Neighborhood Plan.

San Francisco now has another opportunity to take down a freeway while creating major transportation infrastructure improvements in an important area of the city. Currently, the stub end of Interstate 280 creates a barrier between the developing Mission Bay neighborhood and Potrero Hill. At the same time, the Caltrain railyard — 19 acres stretching from Fourth Street to Seventh Street between King and Townsend — forms a barrier between Mission Bay and SoMa. The obstruction will only get worse if current plans for high-speed rail proceed, forcing 16th Street and Mission Bay Boulevard into depressed trenches beneath the tracks and the elevated freeway.

SPUR believes that these challenges can be addressed with a few dramatic urban planning and transportation infrastructure moves that could transform this divided part of the city while also generating funding for several key regionally important transit projects — namely, the electrification of Caltrain, the extension of Caltrain into the Transbay Terminal and putting high-speed rail underground, as opposed to having it travel at street level through Potrero Hill and Mission Bay, which would require crossing streets to go below grade. While the path to making these changes will be a challenging one, SPUR believes that it is worth developing this vision further to see if it can be made into reality.

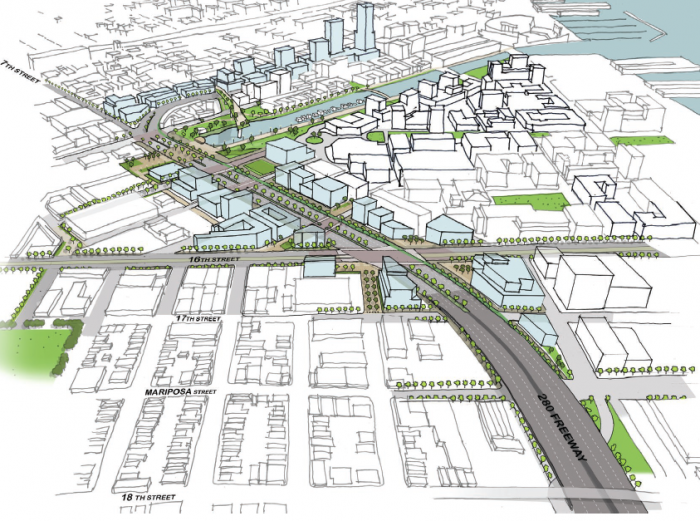

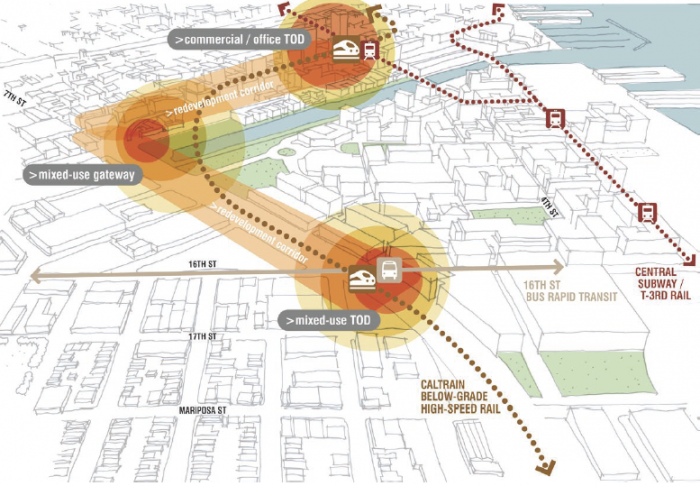

Figure 1

Replacing I-280 with a surface boulevard would create many opportunities for improvement, including the creation of new green spaces that would help to link many neighborhoods together.

Existing Conditions

Right now, several massive infrastructure barriers separate Mission Bay, Potrero Hill and SoMa from one another. I-280 runs along Seventh Street, cutting off Mission Bay from Potrero Hill. Sixteenth Street, which is slated to become a future transit connector with a bus rapid transit (BRT) line, travels under I-280 and across the Caltrain tracks.

To the north, the Caltrain railyard creates a large barrier between Mission Bay, Showplace Square and SoMa, taking up three long city blocks. Pedestrians, bicycles and vehicles cannot cross the site between Fourth Street and Mission Bay Boulevard, and a tangle of freeway ramps clutters the southwest edge of the site.

Currently, the Caltrain railyard is used for train storage and layover and for light servicing such as emptying garbage and cleaning restrooms. All of the important maintenance work is done at Caltrain’s Central Equipment and Maintenance Facility (CEMOF) in San Jose. [1]

Meanwhile, Mission Bay is currently being developed into a regional employment center. The Mission Channel and the park are difficult to access from the surrounding neighborhoods due to their proximity to the freeway ramps, limiting their potential use by workers and residents in Showplace Square, Potrero Hill and SoMa.

To add to these barriers, future plans for highspeed rail call for lowering 16th Street below surface level in order to allow trains to run at street level in the Caltrain right-of-way. If this happens, the entire intersection of 16th and Seventh streets would be subgrade, as would Mission Bay Boulevard. These changes would undermine plans to upgrade 16th Street into a viable transit, pedestrian, bicycle and traffic route.

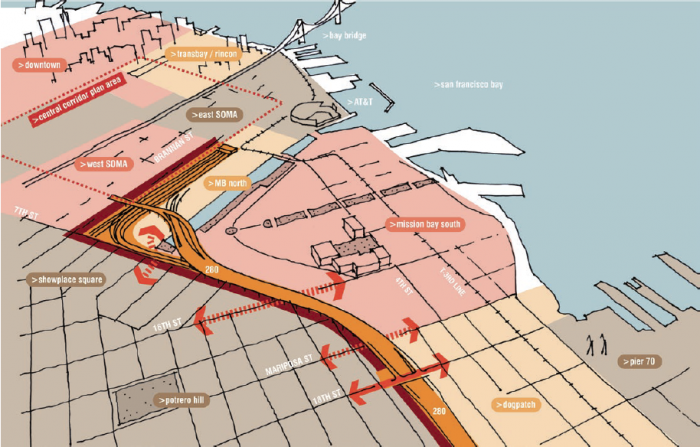

Figure 2

The I-280 freeway and supporting piles form a barrier that is difficult — and in some cases impossible — for pedestrians to cross. The Caltrain tracks run between these piles.

Figure 3

The freeway ramps form a tangle at the edge of the railyards, creating yet another barrier.

Figure 4

Sixteenth Street currently runs at grade, heading under the elevated freeway from Potrero Hill to Mission Bay.

Future Rail Transit Infrastructure

Significant regional transit improvements are slated for downtown San Francisco and the surrounding area. Caltrain has planned a system upgrade to electrify its tracks and purchase new electric trains that allow for faster acceleration and deceleration, more service and greater flexibility regarding the number of cars per train. Additionally, the second phase of the Transbay Transit Center project — known as the Downtown Extension — will provide an underground Caltrain station at Fourth and Townsend and extend Caltrain into the new Transit Center.

While both the Downtown Extension and the electrification of Caltrain are moving forward, they are not yet fully funded. The Downtown Extension will cost $2.6 billion, and Caltrain electrification $1.5 billion, but both projects face significant funding challenges.

At the same time, the California high-speed rail project is in the process of being developed. The idea is that a high-speed train will ultimately connect San Francisco to Los Angeles, with up to four trains per hour arriving at the Transbay Transit Center. The current high-speed rail business plan calls for a so-called “blended system” for the 50 miles between San Jose’s Diridon Station and the Transbay Transit Center, meaning that Caltrain and high-speed rail would share two tracks for most of that distance. This plan will require grade separation at many intersections where trains cross above or below automobile traffic, and without conflict between the two (see Figures 5–7).

Now is an important time to engage in the discussion of how Caltrain operates in San Francisco, as Caltrain and the City of San Francisco are undertaking a feasibility study to explore reducing or eliminating Caltrain’s footprint at Fourth and King. This study will provide an opportunity this year to modify Caltrain’s electrification project as long as the study results do not significantly delay Caltrain’s electrification process or result in substantial additional capital or operations costs. The landscape of future federal funding for major transportation projects is changing to reward transit-oriented development, giving us the opportunity to take a fresh look at potential development opportunities. This is good timing, as it will take at least a decade for high-speed rail to move north and for the region’s other federally funded major transportation projects (Central Subway and BART to Silicon Valley) to be completed.

Figure 5

In the California High Speed Rail Authority’s current proposal, 16th Street would run in a depressed trench under the high-speed rail train.

Figure 6

An elevated view of the High-Speed Rail Authority proposal. Portions of Seventh Street would dip below grade as they approach 16th Street.

Figure 7

The California High-Speed Rail Authority's proposal for Mission Bay Boulevard. Mission Bay Boulevard would run beneath high-speed rail in an underground loop structure.

The Big Moves

There are several big urban planning and infrastructure moves that could leverage the large transportation investments described above while addressing urban design challenges. Taken together, these moves improve the entire area, knitting together SoMa, Mission Bay and Potrero Hill. They also have the potential to generate financial value by developing newly available land and making existing land more valuable. This value can in turn be recaptured by the public sector to fund transit and urban design improvements. Taking such steps could be transformative for the area and for the city as a whole.

The big moves are:

1. Putting Caltrain and high-speed rail underground

2. Tearing down I-280 and replacing it with a surface boulevard

3. Redeveloping the Fourth and King railyards and the surplus freeway parcels

While any of these moves could be undertaken independently of the others, done in tandem they have the potential to greatly benefit all of the surrounding neighborhoods while providing funding for the large transit improvements described above.

Figure 8

Current infrastructure cuts through existing neighborhoods, creating barriers such as the freeway overpass and supporting piles, seen in figures 2–4.

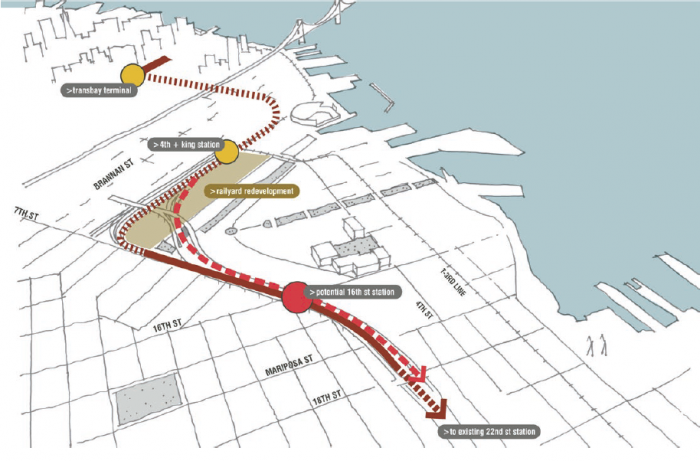

Figure 9

If high-speed rail and Caltrain move underground, many other urban design and transportation benefits could follow. The image above shows one possible version of a future underground high-speed rail and Caltrain alignment.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Big Move #1:

Put high-speed rail and Caltrain underground

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Today, Caltrain runs from the 22nd Street Station through a tunnel under Potrero Hill, proceeding at street level from Mariposa Street into the Fourth and King railyard, where it currently terminates. As described above, Caltrain is expected to run underground, together with high-speed rail, from Fourth and King to the Transbay Terminal as part of the Downtown Extension.

However, there are several issues with the current Downtown Extension plan. The new rail tunnel portal planned for Seventh and Townsend Streets would inhibit the development potential of the railyard. Also, this portal will include a tight track curve on a grade (slope), which will substantially limit train speeds. Furthermore, grade separation will be required for high-speed rail at both 16th and Seventh streets, which will create additional neighborhood barriers as described above.

There are several possible options for the Caltrain/ high-speed rail extension that would reduce its impact on Mission Bay and Potrero Hill, deliver a better urban design and create a superior technical alignment into Mission Bay and the new Transbay Transit Center. All of the options have advantages and disadvantages and require further study. However, all would begin track undergrounding north of Cesar Chavez Street, be run completely under Mission Bay, feature a Mission Bay Station and then proceed to the new Transbay Transit Center.

There are many benefits to these options, all of which would let 16th Street and Mission Bay Boulevard remain at the surface. The rail alignments could eliminate the tight curve at Seventh and Townsend, allowing the trains to run faster. The 22nd Street station could move to 16th Street, or perhaps Cesar Chavez, allowing for a connection to Mission Bay and linking 16th Street bus rapid transit (BRT) and Mission District buses. This underground option also allows the railyard to be developed and for the public to recapture some of the value of that development. Tradeoffs include revisiting the alignment options, and possibly additional costs.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Big Move #2:

Tear down I-280 and replace it with a surface boulevard

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Currently, I-280 runs above street level along and above the existing Caltrain tracks, touching down just south of the Caltrain railyards at Fourth and King. What would happen if I-280 instead touched down between 17th and Mariposa Streets and the remainder of the freeway was replaced with a surface boulevard?

That would allow for radically improved connectivity between Mission Bay, Showplace Square and Potrero Hill, with crossings at 16th Street, Irwin Street, Hooper Street and Berry Street. Mission Creek Channel would become accessible to neighborhoods to the north and west. And parcels of land that previously were used for highway infrastructure could be redeveloped, and their value recaptured.

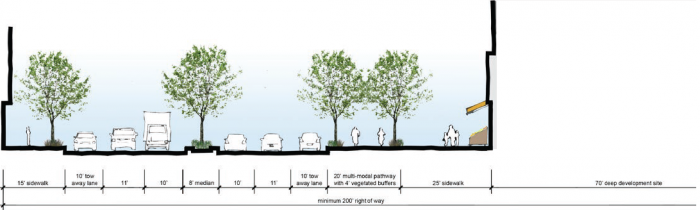

Figure 10

New Mission Bay Boulevard (section). In addition to accommodating cars, the boulevard could include a separated bike lane and graciously sized sidewalks.

The boulevard itself would allow for vastly improved bicycle access, including a separated bicycle path. The boulevard would also support an improved pedestrian experience, allowing for people to comfortably use the liberated street grid. Wide sidewalks could be added to either side of the boulevard to encourage pedestrian activity.

Many other possibilities for urban design improvements would be created as well. A new, greener Hubbell Street would link Mission Creek to Jackson Playground. A series of smaller pedestrian plazas and areas of widened sidewalks could sustain an active streetscape south of Mission Creek. San Francisco could have its own version of New York City’s High Line if a segment of the freeway were repurposed as a raised park. And perhaps most important, the Showplace Square/Potrero street grid could be reconnected with Mission Bay.

Figures 11 and 12

Potential access to Mission Creek Park if the freeway is removed. Access to Mission Creek Park is currently obstructed by the freeway (top). If the freeway were removed, Mission Creek Park would become an asset to the entire area. The lower drawing shows a future view of Seventh Street to Mission Creek and beyond.

Figure 13 and 14

Potential future view from Daggett Street to Mission Bay. The freeway forms a barrier throughout Showplace Square/Potrero Hill. The top view looks east from Daggett Street to Mission Bay. Removing the freeway would greatly improve the connections between Showplace Square/Potrero Hill and Mission Bay.

The removal of the freeway and the undergrounding of high-speed rail and Caltrain offer another way of thinking about land use in the area. With these changes, 16th Street could become an important transit spine, especially when BRT is implemented along the corridor. The area at Seventh and Townsend could become a mixed-use gateway to the rest of the community, and the Fourth and King intersection could become a more successful commercial, transit-oriented development (TOD). Value generated from development in all these areas could be recaptured to fund further public improvements.

Figure 15

Replacing I-280 with a boulevard would create opportunities for new development, including a potential mixed-use, transit-oriented development node at 16th Street if the Caltrain stop were moved to that location.

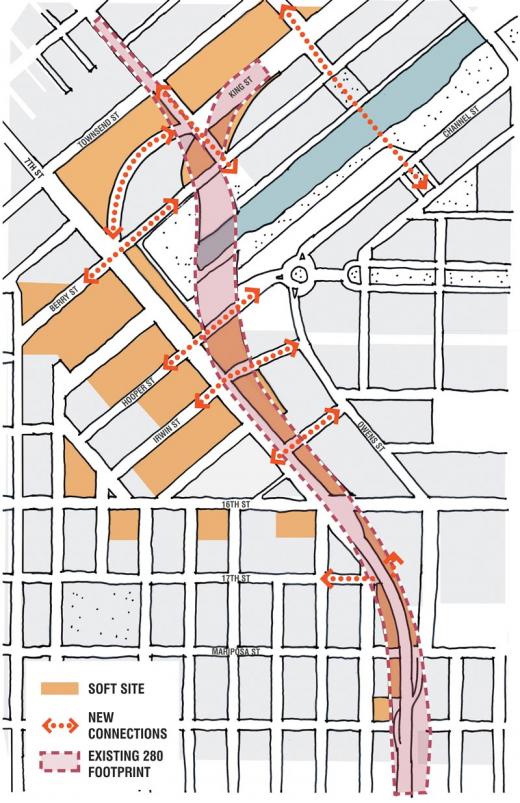

Figure 16

The removal of the freeway would create opportunities for new development and value recapture, both on land previously within the existing I-280 footprint and another land within the vicinity of the new boulevard.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Big Move #3:

Redevelop the Caltrain railyards

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In our 2007 report A New Transit First Neighborhood, SPUR explored the opportunity to develop new buildings over the Fourth and King Caltrain station using air rights (the rights to develop over a piece of land or infrastructure) as a means to pay for both electrifying Caltrain and bringing high-speed rail into the Transbay Transit Center. This study assumed that the railyard would stay in its current location and that any new development would need to be built above the railyards.

Fortunately, a recent San Francisco Planning Department study took this idea to the next level. In its “4th and King Street Railyards: Final Summary Memo,” the department explored two development scenarios for the site: one where the air rights above the railyard are developed while the railyard remains in use (which would require building above the railyard), and another where the railyard is relocated, allowing the entire site to be developed as a blank slate. The second scenario has two variations: one where only the railyard is moved, and another where the railyard is moved and I-280 is replaced with a surface boulevard.

This last scenario would provide the greatest benefits. It would allow for much better urban design, greater development capacity and greater opportunities for value recapture because the land would become more valuable when it is no longer adjacent to freeway ramps. The planning department’s study shows that the net potential value that could be created for the public sector ranges from $148 million all the way to $228 million if the railyard were moved and the Caltrain site redeveloped.

In order to redevelop the railyards, the complex ownership of the site will need to be addressed. As the planning department memo points out, the underlying railyards are owned by ProLogis/Catellus, the entity that owns Mission Bay. However, Caltrain owns an easement to the railyards. This easement is only to construct and operate a railroad, not to undertake other types of development. Any future development on the railyards will need to substantially benefit rail infrastructure and Caltrain operations in order to incentivize Caltrain to alter its footprint to allow development on the site.

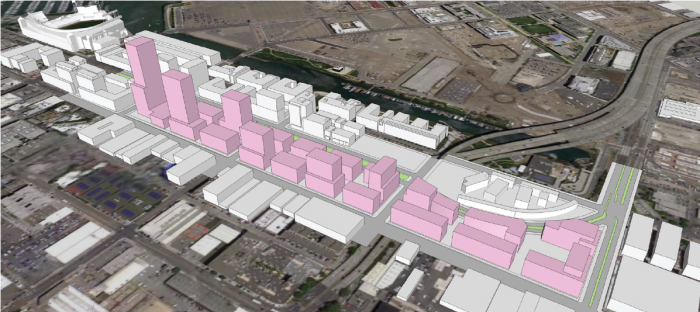

Figure 17

This diagram of the development of the Caltrain railyard from a recent planning department study shows development at grade, allowing for the creation of a new linear park while also making the most of the replacement of I-280 with a surface boulevard. Image courtesy San Francisco Planning Department.

Conclusion

The three big moves discussed here have the potential for tremendous positive impact on many important San Francisco neighborhoods. While each can be completed independently of the other, the benefits are strongest when they are undertaken together.

In order to move this vision to reality, many steps will need to be taken, including completing further study, determining Caltrain’s post-electrification storage needs, engaging in community outreach and education, and determining what resources will be needed to make these changes.

We hope that the City of San Francisco, with participation from regional partners and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), will take the first step and study the big moves outlined above. Studies should include a cost-benefit analysis of each step, as well as an analysis of what the impacts would be to projects that are already in advanced planning stages (such as Caltrain electrification and California high-speed rail). City staff estimate that the cost of completing these studies is roughly $2 million.

We believe that this approach could be a regional and national model for how to use thoughtful development to retrofit past planning mistakes and pay for new infrastructure. We estimate that land value recapture from new development could cover a significant portion of the costs of the big infrastructure moves. Land value recapture won’t work everywhere, but it is a strategy that could be used more broadly in American cities. San Francisco has the potential to bring all the pieces together — neighborhood place-making, environmental sustainability and economic development — by rethinking its transportation infrastructure in the I-280 corridor.

--

[1] CEMOF is a new 20-acre facility located to the north of Diridon Station in San Jose, replacing an old 22-acre yard formerly located on the same site and consolidating most of Caltrain’s maintenance and operations in one location. CEMOF is Caltrain’s central control facility, with water treatment and storage tracks, an on-site fueling facility, service pits and a machine to wash trains. About 150 people work at CEMOF performing maintenance, and roughly 120 Caltrain train crew members are based there.