Every year, SPUR takes a study trip to learn from other cities around the world. This spring we visited Detroit, a city that has long grappled with challenges the Bay Area now faces. We found much to admire in Detroit’s focus on community-based interventions and recovery. See the bottom of this page for more articles about the trip.

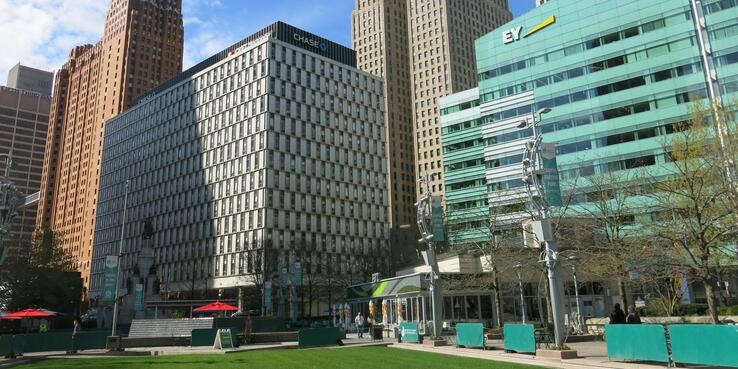

Detroit's economic distress, culminating in the city’s bankruptcy in 2013, is a well-known story. The decline of the American automotive industry, the proliferation of racially exclusive suburbs, and a shrinking population all contributed to the crisis. As a result, much of this once-thriving powerhouse including the downtown area — became vacant or neglected, and the city stopped providing essential services. But in recent years, a remarkable reinvestment in downtown Detroit has breathed new life into the city. City leaders, philanthropy, community organizations, and private investors have come together to revitalize the downtown area, focusing on attracting businesses, fostering entrepreneurship, and creating cultural and entertainment spaces. With a renewed emphasis on bringing more residents, cultural activities, and entertainment downtown, the city has transformed its downtown core. The increased prosperity of downtown Detroit has allowed the city to adopt a balanced budget for the last nine years and to provide an increased level of service for residents.

While downtown has experienced a resurgence, low-income Black neighborhoods have been left behind. Detroit remains the most segregated city in the country. While the median income for white Detroiters increased by 60% from 2010 to 2019, it has remained relatively flat for Black residents. The unemployment rate for Black Detroiters is 1.5 times higher than that of white residents. Thanks to the advocacy of community leaders, city leaders, and philanthropic organizations are now funding new initiatives to ensure that future revitalization efforts are more inclusive and equitable, focusing on programs that promote affordable housing and homeownership, workforce development, and entrepreneurship.

Private Sector Leadership

“I can’t think of a great American city that doesn’t have a great downtown.”

One of the most striking features of downtown Detroit is the influence of a handful of employers and investors with local roots in the city and a commitment to its revitalization. Dan Gilbert, the billionaire founder of Quicken Loans and majority owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers, has spent the last 13 years reinvesting in the Motor City to bring it back to its former glory. For Gilbert, Detroit’s comeback is dependent on creating a healthy and prosperous downtown. In 2010, he moved his businesses to downtown Detroit, adding 8,000 employees. Today, his conglomeration of companies employs about 17,000 people and is the largest private employer and taxpayer in Detroit.

Gilbert formed Bedrock Real Estate, a real estate investment company now led by CEO Kofi Bonner, who met with us during our study trip. Bonner, who had formerly led the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency, explained to us that Bedrock’s vision is to re-densify the downtown core to spur economic development and community vibrancy. For more than a decade, the company has been acquiring historic, underutilized buildings and redeveloping them into housing and offices to bring more life into the area. These investments have been strategically targeted to contiguous buildings across several blocks to create a walkable 20-minute community where residents have all the amenities and services they need within a short distance.

Bedrock owns more than 100 properties in downtown Detroit and has invested about $5.6 billion to date. Initially, almost all of the housing introduced in downtown Detroit was through the adaptive reuse of older buildings. Recently, the company has done more ground-up construction of residential buildings. Ground-floor spaces and public plazas have been programmed for arts, culture, and entertainment activities that support a robust public life. Bedrock believes that investments in community activations in downtown public spaces, such as large music festivals like Afro Nation, are essential to creating an “18-hour city” that pulls in locals and visitors.

IIitch Companies, owned by the founding family of Little Caesars, has also acquired many properties in downtown Detroit, particularly in the entertainment district dominated by sports and entertainment venues, known as District Detroit. Among many other properties, the Ilitch family controls the Little Caesars Arena, home of the Detroit Pistons and the Detroit Red Wings, and the historic Fox Theater. The cluster of stadiums, arenas, and theaters is a huge draw for visitors and local Detroiters, expanding the types of activities downtown. Ilitch is now partnering with Related Companies on the next phase of District Detroit to build six new buildings and renovate four historic buildings into 1.2 million square feet of new office space, two new hotels, and nearly 700 new apartments, with 20% of the homes affordable to very low-income families. Notably, the billionaire founder of the Related Companies, Stephen Ross, is also a native Detroiter.

A short distance from downtown, in the Corktown neighborhood, the Ford Corporation, with support from Google and the State of Michigan, is investing more than $1.4 billion in an economic development project at Michigan Central. The building, an abandoned historic train station, has long been a symbol of Detroit’s disinvestment and blight. Ford’s adaptive reuse project includes a “mobility hub” to incubate research and development startups in the transportation industry, workforce development programs for local Detroit youth, and a new cultural, event, and small business space in the historic train station. The mobility hub, which opened earlier this year, is home to 30 businesses, academics, and thought leaders renting space to leverage learnings, partnerships, and insights as they develop new products that support transportation and mobility.

Public-Private Partnerships

The transformation of downtown Detroit would not have been possible without public-private partnerships. The real estate market in Detroit remains weaker than in other large U.S. cities, making it challenging to do development projects feasibly. Because rents are not sufficiently high to cover the cost of construction, the public sector has partnered with private developers in Detroit, providing federal, state, and local incentives. These incentives have attracted patient investors like Gilbert and the Ford Corporation. Unlike many real estate corporations, they have put a substantial amount of their own equity into projects and are willing to wait decades to turn a profit.

Federal law enables many downtown Detroit projects to take advantage of Opportunity Zone benefits, which provide significant tax breaks to private investments in distressed neighborhoods. To close financing gaps, some Detroit development projects also can take advantage of the State of Michigan’s Transformational Brownfield Plan. It allows mixed-use development projects that generate jobs and economic activity to capture revenue from five sources of income tax, construction tax, and incremental property tax.

Locally, the Detroit Development Authority offers a range of incentive programs for new development projects in Detroit, including a variety of tax abatements, tax increment financing, forgivable loans, and grants. In some cases, the city has provided virtually free land to enable redevelopment of surface parking lots and other vacant properties downtown.

Combined, these tools have closed the financing gap for many projects in downtown Detroit. Recently, District Detroit got state approvals to receive approximately $615 million in future revenues over 35 years. The Detroit City Council approved a partial property tax abatement for the District Detroit project worth $52 million over 10 years. Because the abatement only partially reduces future property tax revenues, the city will still receive a net gain of $77 million in property taxes during that period. Earlier this year, the Michigan Central project received more than $230 million in state and local incentives.

Detroit’s downtown renaissance offers several lessons for the Bay Area’s cities as they struggle to recover from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. First of all, the revitalization of downtown Detroit required the long-term vision of civic leaders, large employers, and city residents. From the onset of the bankruptcy, there was a shared belief that the health of the city was intrinsically tied to the prosperity of the state. “As goes Detroit, so goes Michigan.” Detroiters also recognized that revitalization of the city’s economic core was critical to the recovery of its neighborhoods.

The early investments by Bedrock, Ilitch Companies, and other entities with patient capital made it possible for downtown Detroit to attract more jobs, residents, entertainment, sports, and cultural activities, which revived the city center. In addition, all of those investments were made possible through public sector participation — especially from the local and state government — to close the feasibility gap for transformational projects that create new economic and social activity. The incentives to attract new jobs, residents, and visitors have created more prosperity for the city, enabling it to improve the quality of municipal services. In the coming years, Detroit will face a new challenge as it applies the lessons from the last decade to ensure that the benefits of revitalization are shared by low-income Black Detroiters.

As San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland face high office vacancies, shuttered storefronts, and dwindling foot traffic, it is a good time to assess whether city and state leaders can adopt some of Detroit’s practices. How can government, philanthropy, and major employers work better together to co-create a new vision for our urban centers? Can we revitalize our downtowns in a way that reduces racial disparities and creates more social and economic opportunities for the most vulnerable Bay Area residents and workers? SPUR is committed to exploring these questions and developing solutions for our cities that create a more prosperous, equitable, and sustainable future for all Bay Area residents.

Special thanks go to Camille Llanes Fontanilla and Michelle Kai for their contributions to this article.

Read more coverage of our Detroit trip:

How Detroit’s Food Entrepreneurs Are Invigorating Commercial Corridors and Neighborhoods

Detroit’s Riverfront Transformation Offers Lessons for Revitalizing San José’s Guadalupe River Park

Making Detroit Home: Addressing the Challenges of Housing Stability and Habitability