In early March, the California High-Speed Rail Authority released its draft 2018 business plan, which outlines key milestones ahead and updates forecasts for costs, service levels and ridership. The plan has some important changes from the last version, released in 2016, including a revised funding and delivery schedule of the first operating segment (Central Valley to San Jose) based on lower-than-expected cap-and-trade revenues and a detailed risk-management strategy.

The new plan frames the statewide rail project as a series of several regional projects and presents a path forward that includes:

• Starting service on independent segments in the Bay Area and Central Valley as soon as 2027

• Connecting San Francisco and Los Angeles by 2033

• Supporting the modernization and electrification of the state’s overall rail network

• Investing in cities to spur transit-oriented development around rail stations

This post looks at four key parts of the new plan for high-speed rail: cost, timeline, related rail investments and city-building and development.

How Much Will It Cost?

The first phase of high-speed rail, from San Francisco to Los Angeles, will cost $77.3 billion (up from $64 billion), according to the 2018 business plan. It’s important to note that this cost estimate also includes several updated improvement projects for regional and local rail connectivity along the high-speed rail corridor, such as switching Caltrain from diesel to electric power and increasing capacity at LA’s Union Station, to name just two. Most critically, the authority has billions in hand from federal and state sources and can continue construction for the foreseeable future. Significant new investment will be needed to complete the project, but this is typical as no major transportation project starts with all the needed funds in hand.

Even with higher cost estimates, high-speed rail remains a bargain. Expanding roads and airports to meet the needs of California’s growing population would cost at least $170 billion and might not be possible in many areas: Cities have grown up around existing infrastructure, leaving no room for wider highways and larger airports. Creating more options for people to move around California is not an option but a necessity.

While high-speed rail is under construction, the outlook for new funding could improve. With a GDP of $2.6 trillion, California’s economy is larger than that of some countries with high-speed rail, including Spain. In 2012, SPUR recommended several potential sources of funding that could be raised within the state, including a vehicle license fee and road tolls. These sources remain worth considering for high-speed rail and other related transportation infrastructure investments.

When Will Trains Begin Running?

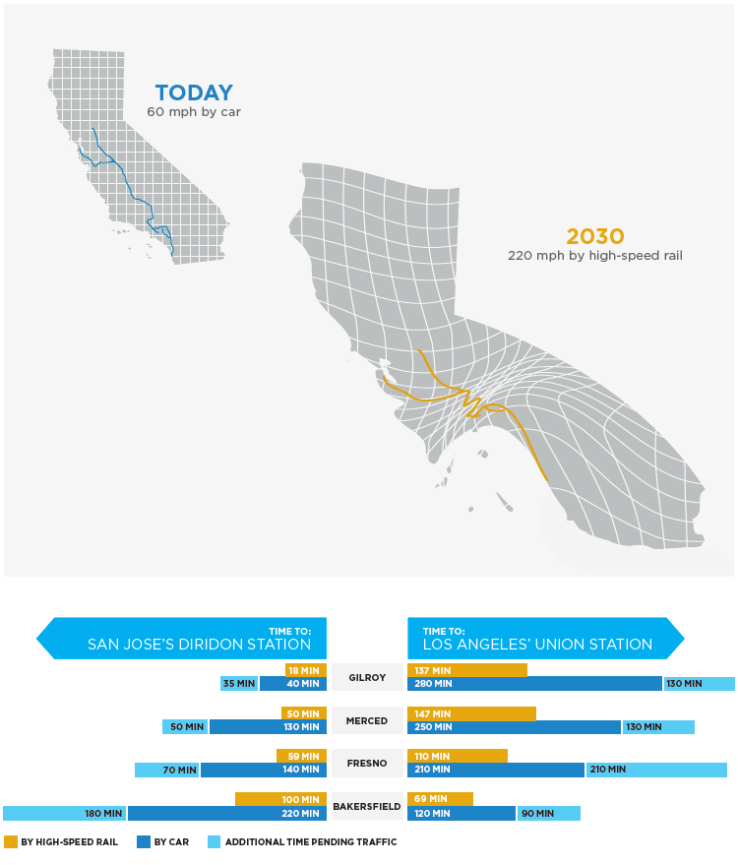

Service between San Francisco and Los Angeles is planned to begin by 2033, and shorter rides will start sooner. In order to begin passenger service as soon possible, the system will be built in segments that will be linked over time. As soon as 2027, high-speed rail service will start on two segments independently: a Silicon Valley segment between San Francisco and Gilroy, and a Central Valley segment between Madera and Bakersfield.

Caltrain’s electrification, which is underway from San Francisco to San Jose and will be completed by 2022, will allow high-speed rail to share its tracks. Caltrain’s tracks and electrification will also be extended roughly 30 miles south, from San Jose to Gilroy. With high-speed service, the trip from San Francisco to San Jose could take as little as 30 minutes, plus another 18 minutes to Gilroy.

High-Speed Rail Will Bring California Cities Closer Together

In the Central Valley, significant progress has already been made on the 119-mile line between Madera and Bakersfield, the other segment that will begin service by 2027.

The Central Valley and Silicon Valley segments will then connect via an additional east-west section that will require tunnels through the mountainous Pacheco Pass (between Los Banos and Gilroy, near Route 152). The 224-mile Valley-to-Valley link will connect San Francisco to Bakersfield, with service in operation by 2029.

Already the Central Valley has captured billions in investment from high-speed rail and thousands of job hours. In the future, rail service should help attract new job and housing opportunities as workers gain easier access to major employment and education centers statewide. Fast rail service will likely relieve some of the pressure from the state’s coastal housing shortage, though land use controls in the Central Valley will be necessary to focus new housing into existing communities, not onto farmland. In addition, the train route will allow San Jose to expand its role as a gateway to the Bay Area.

Finally, after completing its environmental review process by 2022 (yes, this legally required process is lengthy and expensive), the California High-Speed Rail Authority will begin the construction of its Southern California sections, connecting Bakersfield over the Tehachapi Mountains through Palmdale and into Los Angeles and Anaheim.

California high-speed rail is being designed as the backbone of an extensive, integrated statewide rail network with unified ticketing and timed transfers similar to what rail systems in Europe have. The vision set forth in California’s 2018 State Rail Plan is to completely integrate all modes of transit across the state, including high-speed rail, intercity rail and buses, regional rail, local transit and last-mile services such as transportation network companies (Uber and Lyft) and bike sharing. This means public investment in the rail system will serve not only riders with destinations along the high-speed rail route but those taking other modes of transit in other locations.

As a part of the state rail plan, California High-Speed Rail is also funding 18 projects to strengthen and improve regional rail service across the state, including in the Bay Area. Improvements to the Caltrain corridor will result in more frequent local and express service between Gilroy and San Francisco. Other funded projects will bring faster service connecting the East Bay to San Jose, including the completion of the BART corridor to downtown San Jose and Diridon Station.

What Does High-Speed Rail Mean for Cities?

Most importantly, transportation projects are a means to an end. For people to actually use rail in significant numbers, it must connect destinations they want to visit and provide well-planned, walkable development surrounding the station. Recognizing this, the authority has been investing in station area plans for the last several years. Building on these efforts, SPUR has been working with the authority and cities throughout the corridor to identify what they need to succeed in attracting development around their stations and in their downtowns. Last fall we released Harnessing High-Speed Rail, a report that identified a series of policy changes needed to capture the economic development and city building opportunity of high-speed rail. Most critical is the need for local station plans to meet state-level goals (like limiting parking and building up to minimum densities) and for the state to invest more resources into station areas (for example through new tax increment financing tools).

Recent discussions in the state legislature point to an opening to consider replacements for California’s redevelopment agencies, which closed in 2012. But any future program will have to be more targeted spatially (such as around rail stations) and have a stronger role for the state than the prior redevelopment system did.

With the right policy framework, well-integrated high-speed rail stations can help achieve a more compact pattern of urban growth and reconnect neighborhoods by prioritizing active pedestrian and bicycle connections to, from and through the stations. In San Jose, high-speed rail has already entered into a station area planning agreement with the city, the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority and Caltrain to plan and develop an integrated multimodal hub. This effort was inspired in part by a study trip to France and the Netherlands led by SPUR and funded by the Knight Foundation.

Transit-oriented development statewide can preserve farmland and open space while boosting the success of other transportations investments, like Fresno’s bus rapid transit system and Bakersfield’s vision for a light rail system. And as sustainable development and public transportation become more common, places like the San Joaquin Valley, which faces some of the worst air quality in the United States, could see public health benefits as people shift away from cars and air quality improves.

Overall, the new business plan identifies the broad outlines of what is needed to make high-speed rail a reality in California. It is essential now for the state to do two things: first, allow the authority to continue its investments and construction, and, second, partner with cities on policy changes that will help them leverage the rail investments and realize their economic development goals. The business plan makes the case for proceeding full speed ahead, and SPUR will continue working on strategies to further that effort.