The displacement occurring in the Mission District and elsewhere in San Francisco is indisputably tragic. The ever-upward climb in rents reflects a crisis that threatens longtime residents and newcomers alike.

But we should not be fooled into believing that stopping market-rate development or passing moratoriums on new development is going to solve the city’s affordability crisis.

SPUR was relieved that the proposed moratorium on development in the Mission failed to pass at the Board of Supervisors meeting on Tuesday. Here’s why: The proposed moratorium itself is not such a big deal. It’s temporary and in an area of the city where not a lot of housing gets built anyway. What’s more troubling is the thinking underlying it. The Mission has become hyper-gentrified without very much new housing development (less than 100 units a year over the last 15 years.) Development is getting blamed when in fact the Mission has become expensive because the supply of available of housing is so limited. This has created a dynamic where people with more money outbid those with less. A moratorium on new units will not make the neighborhood less desirable, nor will it reduce demand on the housing that already exists. It simply makes housing less available — and makes it likely that more people will be displaced.

There’s no disputing the need for something drastic to be done to protect residents of the Mission and other in-demand neighborhoods. There’s a lot that is already in the works, and with record turnout at the June 2 hearing, we’d like to see that energy get channeled toward productive solutions.

But producing more affordable housing and protecting existing residents are not in conflict with market-rate housing. That is a false choice, and it is counterproductive and misleading to suggest that Mission renters will benefit from a halt on new housing development.

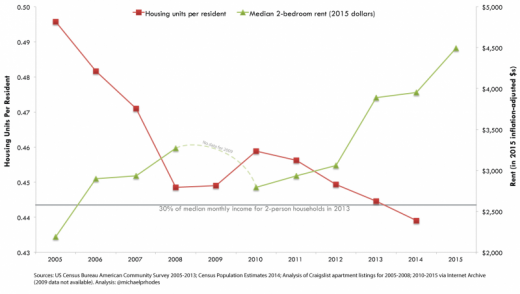

We can look back over the last 10 years and see that whenever San Francisco has had more housing units per capita, rents have been lower.

Housing Units Per Resident and Median 2-Bedroom Rent in San Francisco

If you look at this chart, you can see that we’re currently in the worst part of the curve. In 2014, San Francisco’s peak year of production in the last 20 years, the city saw an increase of 3,514 units for a population of about 850,000 — and it was not enough. In that same year, Seattle built 8,311 new units for an estimated population of less than 670,000. In Washington D.C. rents have fallen more than in almost every other U.S. city, in step with a 35 percent year-over-year increase in available units.

We’ll say it again: There is no way to save the Mission without fixing the housing market — which means allowing a lot more housing to be added. That cannot be done in one neighborhood or even one city; the reality is that we need many Bay Area cities to step up and be part of the solution. But if San Francisco takes the same approach as some wealthy suburban communities and decides to “protect neighborhood character” by forbidding any new housing, then San Francisco becomes part of the problem instead of part of the solution.

So what should San Francisco be doing? SPUR believes strongly that we need to tackle the problem of several fronts:

Let’s build more affordable housing.

Most people know there is a $250 million housing bond on the November ballot. What not everyone knows is that this is just one piece of a much bigger plan — $2.7 billion over 20 years, $1.1 billion over the next 5 years alone — to invest in affordable housing. This is a huge amount of money, and it’s going to make a difference. But that’s not all. The city will be proposing revisions to the inclusionary housing program that aim to make it work better and produce more affordable units. Outreach for the new affordable housing bonus program will launch this summer. Requests for proposals for affordable housing projects on city-owned land have recently been issued for two sites in the Mission (1950 Mission Street and 2070 Folsom Street) and will be issued for the Balboa Reservoir site by the end of the year. This is a strategy on which most people across the political spectrum agree, so there is a lot of progress being made.

Let’s experiment with middle-income housing types.

In San Francisco, those in the middle are particularly challenged: They don’t have sufficient resources to compete in the housing market, nor do they get the chance to compete in a lottery for low-income housing. As there is really no such thing as unsubsidized middle-income housing right now, it’s time to start experimenting. We should work to come up with a new kind of rent-controlled housing that would fill a gap in the current housing delivery system. The proposed housing bond is set to fund moderate- and middle-income housing through existing homeownership programs and to-be-proposed rental programs. There is legislation underway that will allow developers the “dial” option of setting aside units not just for low-income but also moderate-income households. The Small Sites program, launched last year, aims to acquire and protect existing housing for low- and moderate-income households.

The city is already taking steps toward making in-law units easier to build, but it still needs to take much bigger action to allow — and then encourage — production of new in-law units across the city. We should not be naïve about any of these efforts: On their own, they can’t solve the larger crisis. Creating middle-income housing is going to be hard. But that’s all the more reason to start launching more pilot projects — and scaling up the ones that do work.

Let’s improve the approval process to make good projects move faster.

One of the root causes of San Francisco’s housing crisis is the fact that the process makes it extremely difficult to add to the current supply. When new housing is proposed, it takes years — years! — to get permission to build it. Often, the size of projects is reduced during the course of the process, so they yield fewer units than originally proposed. The current process seems to assume we have all the time in the world, and it acts as if it’s no problem to reduce the number of units. This process needs to change. If nothing else, when a project is proposed that fits within the current zoning, it should be allowed to be built immediately.

Let’s increase density in the right places.

Allowing taller and denser development in neighborhoods that are well-served by transit is a natural solution, especially when they are allowed in exchange for building more affordable units. The city is proposing to increase the number of affordable units at Van Ness Avenue and Market Street by increasing heights in this area. It’s a strategy also being pushed by advocates in the Central SoMa plan process. Similarly, sites near the Mission’s two BART stations could provide the right opportunity for a bargain to be struck where greater heights mean additional affordable units. But there is enormous potential to do more.

There is no one right way to add density, but if the city is smart about it, it can increase livability by making sure each new project brings in good architecture and more neighborhood amenities. This is probably the hardest part of SPUR’s housing agenda for many long-time residents to accept: Many people like their neighborhoods the way they are. We do, too. But it does not work to preserve the city in amber when the population is growing by 10,000 people a year. To do so is to accept that only the hyper-rich will get to live here in the long run. We believe it is worth it to accept new buildings in exchange for allowing more people the chance to live in an amazing city.