In Silicon Valley — heart of the global innovation economy — it makes sense to have ambitions for both world-class transit and great urban places. That’s why extending BART service south from Fremont through Milpitas and into the heart of San Jose has been the aspiration of a generation of South Bay leaders, businesses and residents. Their dream is being realized, and two extension projects are now under construction. In Alameda County, the BART extension to Warm Springs/South Fremont will begin service in 2015. In Santa Clara County, the Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) is building Phase I of the BART Silicon Valley Extension through Milpitas to San Jose’s Berryessa district. Service to these stations will begin in 2017.

But getting the next phase of the project funded has stirred up strong feelings — and provided a reminder of all we need to keep in mind when making decisions about long-term transit infrastructure investments.

As initially planned, Phase II of VTA’s BART Silicon Valley Extension would include four additional stations beyond Berryessa: Alum Rock, Downtown San Jose, Diridon Station and Santa Clara. A 5-mile long subway tunnel would serve the first three of these stations. This past fall, VTA was preparing to seek federal funding for the Phase II extension, hoping to build on the momentum of a successful application for the Phase I project, as well as a supportive administration at the Federal Transit Administration. (Phase I received $900 million in FTA New Starts funding to match $1.4 billion in local and state funding.) To make the project competitive for funding from the New Starts program, VTA presented a two-station project alternative, with stations in downtown San Jose and at Diridon Station only. But the possible removal of the Alum Rock station met with strong community opposition. Considering both the opposition and the need to develop a viable financial plan to complete environmental clearance, VTA is now working with stakeholders to further evaluate the project, which the agency’s board of directors will move forward for federal funding in 2016.

The BART Silicon Valley Extension is the largest urban investment the South Bay will make for decades. Decisions made today will be a legacy for generations to come. The route alignment, station locations, station designs, surrounding land uses and sources of financing (both capital for the project and ongoing funding for the operations) will determine whether or not BART Silicon Valley actually achieves its promise. That’s why it was appropriate for VTA to hit pause on the project and revisit the best way to make this extension a reality.

What Is the Promise of BART?

The BART system was dreamed up in the immediate post-WWII years to solve the problems of growing auto congestion. The Bay Area experienced tremendous growth throughout the 1950s and ’60s and in subsequent decades, but much of that growth was suburban and car-oriented. BART offered a promise of rail commutes and the strengthening of the traditional centers, downtown Oakland and downtown San Francisco.

Since BART began service in 1971, our expectations have evolved. The former suburbs that BART largely serves have become employment and commercial centers in their own right. The BART system is now valued as a tool for building great cities and neighborhoods, for addressing climate change and for improving social equity. BART’s impact on the region’s growth has been mixed. Some stations in the urban core saw little to no new development (e.g., North Berkeley). In other instances, BART may have helped fuel outward growth (particularly in Contra Costa County) since it enabled people to live farther from their jobs without increasing their travel time. There is no doubt that downtown San Francisco would not have doubled in office square footage between 1965 and 1981 (from 26 million to 55 million square feet) without BART.

The same evolution of expectations has been true for the BART Silicon Valley extension. What began as an approach to solve traffic on congested highways in job-rich Santa Clara County is now viewed by many as a way to develop thriving neighborhoods and job centers, enabling people to live a lifestyle where transit is a viable travel option.

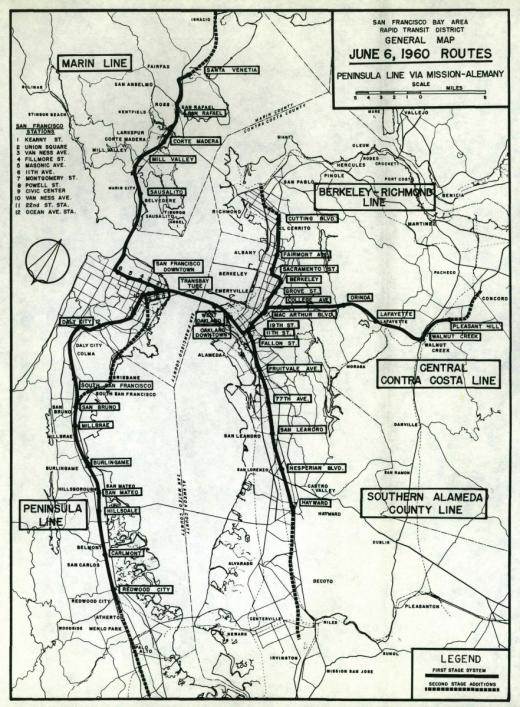

The Original BART Plan

Source: From San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District Supplemental Estimates, June 6, 1960, Parsons-Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel. UC Berkeley Library via flickr user Eric Fischer.

In the 1950s, the BART system’s early designers conceived of a five-county district. But after San Mateo County opted out, Santa Clara lost its proximity and its ability to join the system. The final BART district included only three counties: San Francisco, Alameda and Contra Costa. The reasoning was that the Southern Pacific commuter line (now Caltrain) provided adequate rail transit for the peninsula and South Bay. In the 1980s and 1990s, enough South Bay planners and leaders were interested in connecting to BART that early corridor studies were done for some type of rail connection. Later, the focus shifted to a complete San Jose extension, which became more of a reality in 2000, when Santa Clara County voters approved Measure A, a half-cent 30-year sales tax for BART and other transit projects.

A 2001 study compared options for mass transit from Fremont BART to San Jose Diridon Station. BART through east San Jose was chosen as the solution. But because BART is heavy rail and is not off-the-shelf transit technology, it costs substantially more to build and operate compared to other options considered. (For this reason, leaders selected the “eBART” diesel train extension for the BART extension from Pittsburg/Bay Point to East Costa County.) A Santa Clara station was included because it added political support for BART from a third Santa Clara County city, addressed the need for a BART maintenance facility and provided a connection point for a people mover to the Mineta San Jose International Airport.

A lot has changed since the 2000 sales tax and the original BART studies:

- San Jose’s new general plan. In 2011, the City of San Jose adopted Envision 2040, a general plan that aims to fundamentally change neighborhoods and transportation to support walking and biking and significantly increase transit use. In fact, the plan calls for San Jose to reduce driving from 80 percent of all trips to only 40 percent. However, with the closure of state redevelopment agencies and the fiscal challenges of the Great Recession, the city has fewer staff and fewer resources to jumpstart achieving Envision 2040.

- A revolution in urban transportation. Urban transportation is going through the biggest paradigm shift since the automobile. Uber and Lyft — even Google Maps and the iPhone — did not exist when BART Silicon Valley was first planned. In the 1990s and the 2000s, a multi-modal or car-light lifestyle seemed out of reach — especially in more suburban areas. Today, autonomous vehicles are being developed right here in Silicon Valley and could significantly affect the way we plan transportation.

- The urbanization of tech. Silicon Valley, and the innovation economy itself, is quickly urbanizing and becoming transit-oriented. The highest rents in the region are in transit-accessible places like downtown Palo Alto and San Francisco. Many tech companies are relocating to urban places to attract talent that wants to live and work in dense environments. New development is being built at higher densities, and companies are relying more on commute alternatives, including transit. However, little of this development is currently happening near future BART stations.

- A changed role for transit. Our view of transit has shifted. It is now seen as key to reducing the annual number of vehicle miles traveled, and hence traffic congestion, and it has an important role in greenhouse-gas reduction projects. Reducing vehicle miles traveled is likely to be central to environmental impact analysis in the future.

- The slow decline in federal funding. Federal transportation funding is increasingly competitive and less stable. FTA New Starts funding, commonly used for large transit projects, has been extended through June 2015. But it’s unclear what congress will do with the program after that. The demand for federal transit capital funding far exceeds supply.

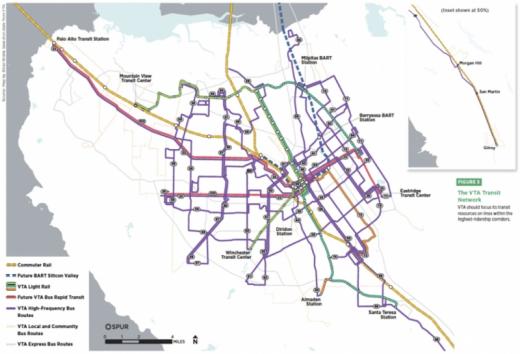

Transit in the South Bay

Source: SPUR

Success for BART Silicon Valley: Key Questions

We need to decide what we value when we make decisions about investing in a BART project (or any transportation project). For SPUR, a successful BART project powers a virtuous cycle: quality transit supports compact, walkable neighborhoods rich in jobs and amenities, which then supports more transit usage, which then supports better neighborhoods, and on and on. SPUR has already laid out recommendations pertaining to BART in Silicon Valley in our reports The Future of Downtown San Jose and Freedom to Move.

VTA expects that its board will decide on a preferred project in early 2016. We know that the agency will be focusing on finding the best number and location of stations for a Phase II project before that time. But SPUR is exploring four other very important questions:

1. What makes a good BART station location?

Ridership largely depends on providing access to destinations with jobs. More stations means more destinations — but it also means more costs. In anticipation of BART, increases in jobs and housing are planned around the proposed stations, but there is a question about whether it will be enough and when it would happen. Three of the station areas have recently adopted plans: The Five Wounds Urban Village Plan, the Diridon Station Area plan and the Santa Clara Station Area Plan. The City of San Jose’s 2000 Downtown Strategy and several other urban village plans will also guide development around BART stations.

Today, not enough people live and work within walking distance to the planned BART Silicon Valley stations to fill up the train cars. The BART Silicon Valley extension plan relies on park-and-ride facilities to deliver riders. This is why 4,800 dedicated parking spaces are planned along the extension. But there is an important tradeoff between the cost of parking and the potential for neighborhood-based ridership. Some of the highest ridership BART stations in the region have no designated parking. People arrive and depart from these stations using other transit, walking, cycling, taxies and shuttles. The FTA does not require parking, but it does fund it if needed for ridership.

BART service to San Jose will be added to a web of existing transit infrastructure and services: VTA’s buses, light rail and bus rapid transit (under construction on Santa Clara/Alum Rock); the local DASH shuttle; Altamont Commuter Express; Amtrak Capitol Corridor; and a soon-to-be electrified Caltrain. Together, an estimated 30,000 people or more could arrive in downtown San Jose on transit. (Based on SPUR analysis that assumes peak-hour capacities of 3,000 per hour on light rail, 1,200 per hour on bus or bus rapid transit, 3,600 per hour on Caltrain and 8,000 per hour on BART.) For comparison, there are about 36,000 jobs in downtown San Jose today. (Based on SPUR analysis. See our report The Future of Downtown San Jose.) There will be a lot of transit running to and from downtown San Jose; substantial job and housing growth will be key to filling transit seats. The sooner that development happens, the sooner BART would have the ridership it hopes for. The South Bay’s experience with its light-rail system offers many lessons on the importance of coordinating land use development with transit investments. SPUR suggests cities, VTA and public and private land owners evaluate all the ways we can facilitate development in station areas. Precise station locations and portal locations (for underground stations) would also impact ridership and land use outcomes, and they deserve careful planning.

2. How can we create seamless intermodal connections to BART?

Will there be a seamless, cross-platform connection between BART and Caltrain at Diridon Station? That would give travelers going to peninsula towns from the east side of Santa Clara Valley a strong incentive to use BART, while making it easy for Caltrain (and future high-speed rail) riders to access destinations in the East Bay. Essentially, we should aim to design the connection as though these two services were a single operator (resembling the BART-to-BART cross-platform connections at MacArthur Station in Oakland, for example). Caltrain electrification and the completion of the Caltrain/high-speed rail downtown extension in San Francisco could create a true high-capacity ring around the bay.

Easy local connections to light rail, buses and shuttles are also going to matter in delivering on the promise of BART. VTA’s BART Transit Integration Plan begins tackling the question about redesigning the transit network as Phase I BART stations come on line.

3. Where would the funds to build a great BART Silicon Valley Phase II project come from?

Constructing all 16 miles of the complete BART Silicon Valley Extension is now estimated to cost $8 billion. This is not a minor problem: VTA’s entire capital program budget (the Valley Transportation Plan) is around $13 billion for the period from 2013 to 2040. This includes projects for transit, highways and the local transportation system (local streets and roads, technology to manage the roads and bike/pedestrian facilities). Measure A was passed at the height of the dot-com boom and has not pulled in as much money as expected. Completing the planned project will require substantial additional funding.

One approach to make BART construction affordable is to cut costs by reducing the size or complexity of the project. The danger of value engineering is a transportation project that does not deliver as many benefits over its lifetime. The possibility of phasing stations or parts of the service in over time has also been floated. The West Dublin/Pleasanton and Irvington BART stations have been handled this way. (The recent passage of the Alameda County Measure BB sales tax adds $120 million to complete the Irvington station.) Another strategy used occasionally to fund rail projects is value capture, which captures some of the increase in land value around BART stations. This tool is being used for the Transbay Transit Center in San Francisco and also for the 7 line extension of the New York City subway. Given the market dynamics and generally low densities around most future BART stations in the South Bay, it is unlikely that value capture could produce significant funding. But it is still a tool that should be considered, particularly for Diridon Station.

Another source of funding for BART is simply shifting funding. It’s worth looking at all of the other projects in line for funding in Santa Clara County and deciding if they are the most strategic investments. Finally, the costs of using debt financing for a project of this size are also substantial and need to be better understood.

4. How would VTA afford to operate BART and still continue to operate an effective countywide transit network?

Transit service will need to grow throughout the county and effectively integrate with BART. We need to make sure there are enough resources for all of that. Because Santa Clara County is not part of the BART District, the BART Silicon Valley Extension will be built by VTA according to BART’s facility design standards and governed by VTA. VTA will pay BART to operate service according to a comprehensive agreement signed in 2001. For comparison, the 5.4 mile BART extension from Fremont to Warm Springs/South Fremont is being built by BART and will be governed by the existing BART board.

Farebox revenue will help pay for BART operations, as will a second sales tax, which passed in 2008. (To get federal funding to build Phase I, VTA had to show enough local funds to prove it could afford BART operations. Voters approved another 1/8 cent sales tax, which has been collected since 2008.) In addition to funding day-to-day operations of BART, there are large unfunded infrastructure and equipment expenses to keep the entire BART system running in state of good repair, estimated at $4.8 billion. (See A State of Good Repair for BART: Regional Impacts Study.)

Learning and Deciding

VTA has elected to take another year before applying to the FTA New Starts program for funding and will begin the federal and state environmental process in 2015. We have a bit of time to ensure that BART is both a great transportation project and a great city-building project.

BART is expensive to build, and deciding on the set of stations to fund will not be straightforward. But there is so much more to get right than just the number of stations. SPUR looks forward to learning more and addressing the difficult questions ahead.