It came and it went, but Los Angeles as we know it did not come to a terrible end. Carmageddon — the 52-hour, 10-mile shutdown of the 405 freeway last month —passed quietly into history, becoming one of L.A.’s lightest traffic days ever. Angelenos stayed off the freeways; bicyclists challenged a Jetblue flight to a race — and won; people used trains and buses to get around or just stayed in their own neighborhoods. The predicted gridlock simply didn't happen.

Most Southland residents are no doubt thankful nothing apocalyptic happened and ready to forget about it, possibly writing the whole thing off as hype. But could the lack of a nightmare scenario from a major freeway closure signal Angelenos' willingness to reclaim their city from the automobile? We asked ourselves what it might look like if L.A. adopted some of the solutions that SPUR regularly advocates for the Bay Area. Could this be the start of a new movement — or at least a test run for handling a future crisis?

Carmageddon as a movement

San Franciscans have embraced Sunday Streets, the series of planned closures that open city streets to biking, walking and other uses. Could this work down south? Even seemingly car-obsessed L.A. has a long history of reclaiming the street as public space. In the 1960s UCLA students stormed the 405 in protest of USC being named to the Rose Bowl. More recently the streets of downtown L.A. became the site of CicLaVia, a Sunday Streets-like closure of several miles of roads for bike and pedestrian use.

While the 405 would hardly be the most appropriate space for biking or alternative uses, Angelenos' ability to painlessly adjust to not using their cars for one weekend shows that carlessness can perhaps work in L.A. Events like CicLaVia and downtown L.A.’s monthly Art Walk show that there is indeed demand to get more types of use out of the city's streets.

What if these ideas were institutionalized into a movement, closing large sections of streets to cars on a regular basis, simultaneously allowing the public access to its streets and its neighborhoods while promoting awareness of carlessness in L.A.?

Carmageddon as a test

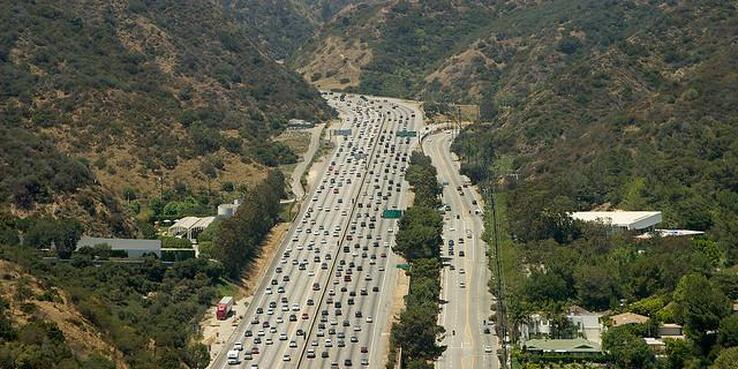

What if the 405 was rendered inoperable or greatly impaired for a longer period of time than just a weekend? This could be a result of a natural disaster or because, as many have suggested, the traffic problem in the Sepulveda Pass (which connects downtown to the San Fernando Valley) hits critical mass. Life in LA would have to continue — but how?

Leading up to and during Carmageddon, many Angelenos chose to work from home or commute outside of rush hours. That idea could be expanded with the creation of co-working sites in the San Fernando Valley, which would reduce demand on the Sepulveda Pass. The city could also creat incentives for employers and employees to operate outside of normal commuting hours, distributing the usage of the freeway more evenly.

These options, while helpful, would not fix the problem entirely. There is already heavy off-peak congestion, and some people already commute outside of rush hour. A more long-term solution might look similar to an idea SPUR has advocated for the Bay Bridge: dedicated lanes for public transit. Los Angeles could dedicate one lane of the 405 in either direction for bus rapid transit (BRT), extending the San Fernando Valley Orange line down the 405 corridor. In addition to expanding the capacity of the already strained freeway, this BRT line could connect to many of the city’s most heavily used streets.

L.A. weathered Carmageddon well, but instead of taking this short-term victory for granted Angelenos might see it as a first step in thinking about long-term traffic solutions. Simply widening a freeway to add carpool lanes doesn’t address the root causes of traffic. Carmageddon is proof that L.A. can survive without over-reliance on cars. It is also a testament to the fragility of an over-relied-upon, mostly single-mode system. While we recognize that L.A. is very different from the Bay Area, we hope our southern neighbors will look to a more long-range set of solutions for an obviously congested and overused road system.