San Francisco is running out of funds to build affordable housing, and the city will need to make changes quickly to fix the problem. How did this happen and what can be done about it? Many factors are at play, but a look at data from the city indicates that a combination of rising construction costs and new requirements is slowing down new development and curtailing incoming funds from development fees. SPUR has five immediate suggestions for how to address the problem before it gets worse.

Changes to Inclusionary Housing Requirements

In 2016, San Francisco voters passed Proposition C, which substantially increased the city’s inclusionary housing requirements — the percentage of affordable housing that every new market-rate development must either include on site or pay to build elsewhere. Developers called the increase onerous, leading to a series of negotiations after the election.

| Before 2016 Prop. C | After 2016 Prop. C | Under Latest Legislation | |

| Affordable units to build on site | 12% of total units | 25% of total units | 18% of total units increasing to 24% over time |

| Affordable units to pay for offsite | 20% of total units | 30% of total units | 30% of total units |

While subsequent legislation modified the on-site requirement, the offsite number was never lowered, meaning that a market-rate developer building a 100-unit housing project must pay the city the cost equivalent of 30 units of affordable housing. The city’s payment schedule lists the offsite costs as ranging from $198,008 per studio unit to $521,431 per four-bedroom unit. Typically, a market-rate developer must pay these fees to the city upon pulling a building permit.

Unfortunately, due to a variety of factors — rising construction costs, high land value, high impact fees including those from Prop. C, and the softening of the rental market — market-rate developers are applying for building permits at a much lower rate than in the past few years. This means the city is not collecting offsite fee payments in sufficient quantities to build new affordable housing that is already going through the planning process. When developers are able to start construction, they are most often opting to build affordable units on site, depriving the city of funds that could be paired with low-income tax credits and other financing sources to develop 100 percent affordable housing projects.

Stalled Market-Rate Housing

Developers have proposed more than 44,000 new housing units in the city, so why is the number of actual permit applications dwindling? First, 15,330 of those housing units are seeking initial approval from the Planning Department, a process that can take years. The remaining 29,000 have received approval but have not yet taken the next steps toward construction. Most of these — over 27,000 units — are in master planned developments like Hunters Point Shipyard, Pier 70 and Mission Rock that will move forward in phases and are not expected to be fully completed for 10 to 15 years. That leaves nearly 2,000 units that could be moving forward today but are not, including more than 800 that have been sitting static for over a year. For many of these projects, the issue is whether the developer will still be able to cover costs and loan payments and meet investors’ expected returns. A building that may have been financially feasible when it was first proposed two or three years ago could cost millions more in today’s environment of higher construction costs and development fees.

If we put aside the large master planned communities that will take years to develop and look just at smaller infill projects, it appears that Prop. C has curtailed the number of housing units that developers are proposing to build.

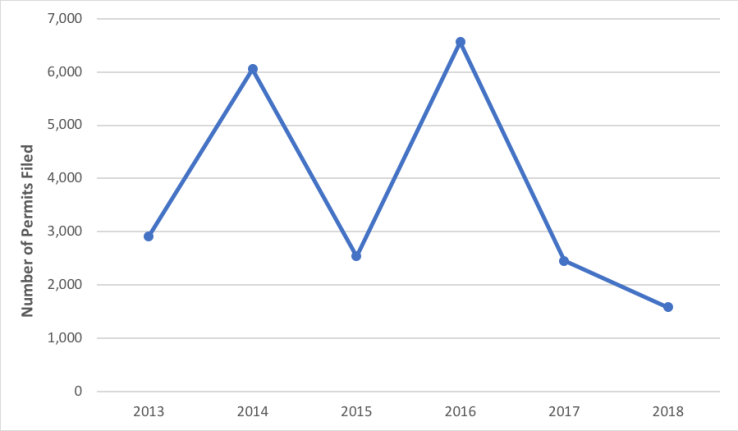

Permits for Infill Housing Units Filed at SF Planning Department

In a healthy economic cycle, half of the units filed in a given year should start construction within three years. Given the slowdown in infill applications, including fewer than 2,449 units in 2017 and 1,580 thus far in 2018 — and given that major developments like Parkmerced, Mission Rock and Pier 70 have extensive infrastructure needs and will take several years to build out — achieving the late Mayor Ed Lee’s goal of building 5,000 units per year will be largely unattainable.

Impact on Affordable Housing

What does this mean for funds allocated to the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD) to build affordable housing? Market-rate housing applications are decreasing overall and of the units that the city anticipates completing over the next six years, only 22 percent are projected to satisfy their affordable housing requirements by paying offsite fees. The impact is dramatic. MOHCD has received only $10 million in inclusionary fees for fiscal year 2018–19 and anticipates it will receive another $65 million from market-rate projects (assuming those projects are not delayed), bringing its total for the year to $75 million. Given that each affordable unit currently receives a subsidy of approximately $313,000 per unit, that yields only 240 units of affordable housing. This is much lower than the more than 500 units the city was producing each year from 2014 to 2016, before the passing of Proposition C. What happens after this $75 million is exhausted is unknown. Market-rate construction will not be an immediate source of revenue given that construction costs have increased for 21 straight quarters and top rents in the city are beginning to plateau.

In recent years, the city could reliably estimate the rate of incoming inclusionary fees and plan accordingly. However, given the increase in construction costs, high impact fees, delays at the building department to approve plans, and the small number of entitled projects that are applying for building permits, it is becoming very difficult to estimate the flow of inclusionary funds to the city.

What Can the City Do?

Developing new market-rate housing is key to providing more funds to build affordable housing. What can San Francisco do to incentivize market-rate projects to pull a building permit and start construction? Here are five policies the city can pursue:

1. Audit the building code to reduce costs.

Reducing construction costs is the most important factor in kickstarting new development. In fact, last year San Francisco won the dubious distinction of being the world’s second-most expensive city to build in. Many of these costs are due to expensive building code requirements that are layered on top of the state’s building code. In our Blueprint for San Francisco’s Next Mayor, SPUR called for the mayor to establish a technical committee of contractors, architects, engineers and other experts to perform an audit of the city’s building code, with the intention of reducing the production cost of housing. Such a committee would help alleviate the high cost of construction in the city and make currently infeasible projects feasible.

2. In the short term, support pre-fab construction outside of San Francisco.

Incorporating factory-based prefabrication in steps of the construction process can reduce costs considerably. But pressure from some local labor unions has made this a politically unpopular choice. Mayor Breed has proposed building a factory within city limits to support local jobs — a project that could take years to complete. SPUR’s Blueprint recommends that the mayor and Board of Supervisors lend their support to factory-built housing for projects currently in the pipeline. For the short term, at least, this should include factories based outside of San Francisco.

3. Let the Controller’s Office set inclusionary requirements.

The Board of Supervisors should de-politicize the inclusionary housing process by giving the Controller’s Office the authority to set and modify the requirements, as opposed to keeping it with the Board of Supervisors.

4. Allow more projects to use the density bonus.

The Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors should permit projects that were not entitled at density bonus levels initially to be re-entitled at the higher density bonus unit counts, as permitted by state law, which could help make market-rate projects feasible.

5. Hit pause on planned increases to inclusionary requirements.

This one won’t affect funding for offsite affordable housing, but it could increase the likelihood that more affordable units will be built on site. The Board of Supervisors should introduce legislation to pause the annual automatic 1 percent increase in the on-site inclusionary housing requirements, scheduled to take place in early 2019. SPUR recommends that the board say no to the 2019 increase in order to prevent additional costs from further burdening the financial feasibility of proposed market-rate projects. Taking a one-year break could also allow time for costs to come down.

These are just a few ideas that the city can pursue in order to address its lack of affordable housing funding. Recent policies have pushed market-rate developers to become some of the main funders for affordable housing. That means the city need to aggressively pursue all means necessary to start construction of these stalled projects in order to fund and build the affordable housing we need to house our workforce, our homeless and our neediest families.