High-speed rail is unlike any infrastructure investment ever implemented in California. It is large and complex and will take a long time to build out. But it is also potentially transformative — not only to how people travel but to how communities will grow and develop for generations. If implemented well, it can help leverage the billions in public investment that have already been committed to achieve important state goals like combating climate change, preserving farmland and expanding economic development, and supporting downtown revitalization.

High-speed rail has the potential to be as significant to shaping California’s future as 20th century in- vestments like the California State Water Project, the state highway system and the California Master Plan for Higher Education (which linked the University of California, California State University and California Community College systems). These investments in water, roads and higher education were critical in propelling the state’s economic success in the second half of the 20th century. Missing among those three major investments was a comparable statewide investment in rail transportation, akin to what took place in countries like Japan, France, Spain, Germany and the United Kingdom at that time.

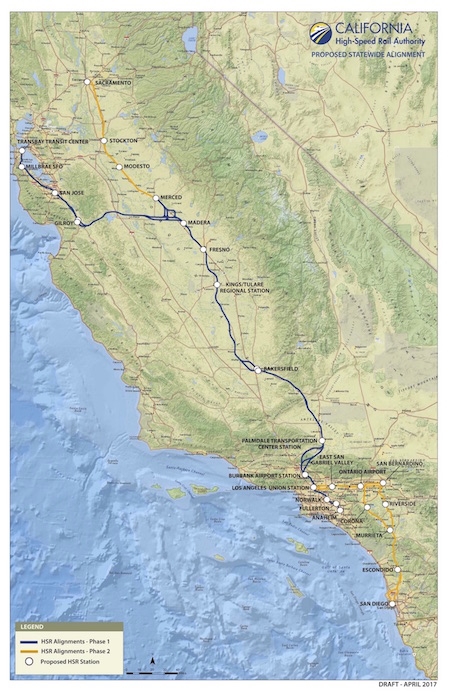

Today, after decades of discussion and planning, California is now building a high-speed rail system. The first segment of the project, which will connect Bakersfield to San Jose, officially broke ground in 2015. Service from the San Joaquin Valley to the San Francisco Bay Area is expected to open in 2025 and connect into Los Angeles in 2029.

In 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A to “initiate the construction of a high-speed rail system that connects the San Francisco Transbay Terminal to Los Angeles Union Station and Anaheim, and links the state’s major population centers.” The proposition authorized the selling of $9.95 billion in bonds to finance high-speed rail in California and make related regional rail investments. With support of those bonds, federal funds and additional state resources through the California Greenhouse Gas Cap-and-Trade Program, the rail project is underway.

Prop. 1A noted two key goals: 1. “stations shall be located in areas with good access to local mass transit and other modes of transportation,” and 2. “the high-speed train system shall be planned and constructed in a manner that minimizes urban sprawl and impacts on the natural environment.” These goals signal an approach to planning high-speed rail that aims to integrate the train into existing places and communities and shape their growth in a positive way. As a reflection of that goal, Prop. 1A identified a route that passes through the center of cities such as Fresno and Bakersfield that were bypassed when Interstate 5 was built along the west side of the San Joaquin Valley. Interstate 5 prioritized a direct and speedy trip between north and south, not the connections among existing cities (who remained connected on California State Route 99).

In selecting an alignment through the center of these valley communities, Prop. 1A deliberately sought to not only connect the San Francisco Bay Area with Los Angeles, but to make the cities in between — most notably Gilroy, Merced, Fresno and Bakersfield — more closely connected to each other, as well as to the regional economies on the coast. Also, as an indication of the concern about potential urban sprawl in the San Joaquin Valley (such as around the town of Los Banos, just over the Pacheco Pass from Gilroy), the measure specifically noted that there would be no station between Gilroy and Merced.

The selected high-speed rail alignment will connect San Joaquin Valley cities more seamlessly with each other and reconnect them to the coasts, which has the potential to improve their economies. Instead of the business-as-usual process of converting farmland at the city’s edge to housing and urban development, high-speed rail could contribute to revitalizing existing downtowns and shifting some of the growth back toward urban centers.

To fully realize these and other benefits, we must combine the improved accessibility that a fast train brings with targeted policies and investments, particularly from the State of California, to transform the economies of the cities with high-speed rail stations. Some evidence suggests that when a new high-speed rail system is built, intermediate cities along the route can lose out relative to the larger, more established cities if they do not plan for how to make best use of the opportunity, or if they neglect their existing assets (such as a historic downtown).

Further, local governments cannot be expected to rely solely on the real-estate market to deliver new development around their stations and in their often- struggling downtowns. Nor can they rely on their limited existing funds to pay for civic investments like new public plazas and parks, upgraded sidewalks or expanded transit and bike lanes. There must be new financial tools and investments to pay for this infrastructure, as well as to initially subsidize new commercial and residential development, as current market rents in these cities would not cover the cost of construction.

Funded in part by a $9.95 billion state bond, high-speed rail is the state’s largest investment in decades and has a legal requirement to operate trains without an annual operating subsidy. Its development and implementation must consider the state’s needs in balance with local ones. The state cannot be expected to spend tens of billions on the rail system and then leave all land use decisions to local governments. And the California High-Speed Rail Authority and its future operator cannot be confined to the business of running trains. They need to be able to grow ridership and capture revenue through real estate development at high-speed rail stations and in the neighborhoods around them.

Current tools and approaches to transportation and land use integration are not sufficient for the opportunity of high-speed rail. To fully realize the benefits of our investment, we need to change how we approach planning and develop new tools to capture the economic growth potential of a high-speed train. This is the critical task ahead for the station cities, the High-Speed Rail Authority, the state legislature and other state, regional and local partners.

Three key actions will be necessary: First, there needs to be a single entity — managed jointly by cities and the state — to carry out the development in the station area. Second, there should be a major financial incentive — such as a new form of tax increment financing — for cities to revitalize their down- towns, and use some of those revenues to support growth around the rail stations. Third, there must be a local and regional commitment to reorient growth towards existing communities by establishing stricter development controls at the urban edge and thereby preserving important farmland and open space. SPUR’s full list of recommendations will be included in our final report when it is released this summer.