Photo by Joel Puliatti, courtesy of the San Francisco Wholesale Produce Market

Photo by Joel Puliatti, courtesy of the San Francisco Wholesale Produce Market

This article is excerpted from the SPUR report "Locally Nourished." Read the complete report at spur.org/locallynourished >>

Each day, millions of Bay Area residents shop at grocery stores and farmers’ markets, cook meals at home, dine at restaurants and compost their food waste. Individually, our food choices impact our taste buds, pocketbooks and health. Collectively, though, our choices have an enormous impact throughout the region — on the future of agricultural land, the viability of thousands of food businesses and the size of our environmental footprint.

Our food system, which encompasses the full cycle that food takes from field to fork and back to the field, is simultaneously regional, national and global in scale. Our region’s food businesses export, import and conduct business locally. Bay Area residents and businesses benefit from this trade, whether through the growth of local winemakers and cheesemakers distributing their products across the globe or through our access to imports of chocolate, coffee and sugar.

But we gain distinct, measurable benefits from a regional food system — one in which individuals and businesses prioritize purchasing and spending within the region — that the national and global food economies cannot provide. Farms and ranches in the nine-county Bay Area cover more than 2 million acres and support a greenbelt of open space and working land that helps focus growth into urban areas and away from sprawl. Local farms, food manufacturers, distributors, grocers and restaurateurs provide more than 400,000 jobs and, when they buy from each other, help circulate more of the area’s wealth within the region. Residents, businesses and local governments reduce the region’s carbon footprint by diverting food waste from the landfill and producing compost sold to local farms. Alongside these measurable benefits, the regional food system provides the intangible but powerful benefits of promoting ecological awareness, preserving cultural heritage and fostering a unique sense of place.

While the region has many opportunities with its food system, it also faces the potential loss of 15 percent of its remaining farmland and 7 percent of its rangeland in the next 30 years. To capture more of the land use, economic and environmental benefits of agricultural land, SPUR's new report Locally Nourished supports three broad goals:

The Bay Area is rightly known for being a leader on many food issues — including sustainable agriculture, small to midsize food manufacturing, and municipal composting. In recent years, numerous initiatives, ranging from the San Francisco Urban-Rural Roundtable to the creation of food policy councils, reflect a growing understanding that policy is needed to prevent the loss of agricultural land, as well as the loss of food businesses and an aspect of the region’s identity. The challenge ahead is to continue this leadership and emphasize the positive impact of a greater regional focus within the food system so that more local residents and businesses share in its benefits.

The food system includes five main stages: production, processing, distribution, retail and waste. For this study, we define the region as encompassing the nine counties adjacent to San Francisco Bay.1 We choose to limit our scope to the nine counties of the Bay Area because they share regional governance bodies and they are the focus of most of SPUR’s work. We acknowledge, however, that this scope excludes the Central Valley and Salinas Valley, agriculturally rich areas that provide a significant portion of our produce and are within a few hours’ drive of the Bay Area. Though we chose to focus on the nine-county Bay Area, many of the recommendations in our report are applicable within a more broadly defined region.

SPUR believes that future Bay Area growth should be directed into existing urban areas. We have long supported the preservation of our region’s open space, including wilderness, parkland and working lands.[2] In part, this is because these areas are uniquely valuable as aesthetic, cultural and ecological resources. But our support for preserving a greenbelt of open space around the Bay Area also stems from an interest in building a buffer against sprawl. The historic pattern of spreading our homes and businesses farther and farther away from urban cores has increased our commutes and thus, our greenhouse gas emissions. A recent study sponsored by the California Energy Commission concluded that infill development and agricultural preservation could be a county’s most effective strategy to reduce its greenhouse gas impact because of reduced transportation emissions and decreased residential energy use resulting from urban density.[3]

Building and maintaining a greenbelt requires investment, and agricultural land is often an economical option. Preserves and parkland frequently have high initial costs to acquire the land, as well as the ongoing expense of staff time to maintain, manage and patrol the land. Agricultural land, on the other hand, can often be protected from development for less money and is managed primarily by farmers and ranchers, which can reduce the costs of land management borne by the public agency or private land trust that owns the land.

Not all of the benefits of a regional food system can be measured as quantitatively as greenbelt land acquisition and management cost, economic growth or reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from diverted food waste. The educational benefits of farms, ranches, food processors and even compost facilities operating in close proximity to urban areas are intangible yet invaluable in connecting people to the source of their food, ecological cycles, the taste of fresh food and the scale of land and resources required to feed ourselves. Similarly, the food system is an integral part of not only the Bay Area’s economy but also its heritage, cultural history and landscape. If the Bay Area loses this part of its economy, it loses part of its identity as a foodproducing region. Though these values are impossible to quantify, they are important benefits of a stronger regional food system that should be included in the policy discussion.

Figure 1: Defining the Regional Food System

Diagram by Carsten Rodin

While there are benefits of having agricultural land in a greenbelt, there are costs as well. Poor farming practices can result in soil erosion, water contamination and habitat degradation. An active farm can produce noise and pollution that can affect neighbors. Sustainable farming practices aim to mitigate many of those impacts, but working lands can have a negative impact on the land and nearby communities. Recognizing this, SPUR believes that a successful greenbelt includes a balance between natural areas, recreational open space and agricultural land.

The Bay Area’s farms and ranches yield an enormous variety of products — including fruits and vegetables, meat, dairy and flowers. At right is a list of the top five products in each county, listed by their value in 2011. Because the counties report crop yields differently, the category labels vary. This listing only provides a small sampling of the food grown and raised in the nine counties.

While the variety and amounts are quite significant, the agricultural productivity of the counties adjacent to the nine-county Bay Area is of a different order of magnitude. No Bay Area county produced more than $600 million in agricultural products in 2011. In contrast, Monterey, San Joaquin, and Stanislaus counties all produced more than that amount in 2011.

Figure 2: The Top Five Agricultural Products by Value in Bay Area Counties, 2011

Source: SPUR analysis of 2011 County Agricultural Commissioner crop reports [4]

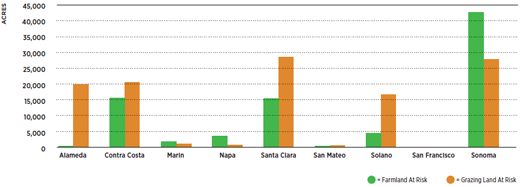

A good portion of the Bay Area’s farms and ranches, integral to both the region’s greenbelt and its overall food economy, are at risk. As history has shown, if unregulated market forces drive development, then sprawl will extend into more and more of the Bay Area’s land. Since 1984, the region has lost more than 200,000 acres, or 8 percent, of its farmland and ranch land. During this period, the loss of farmland has been more acute (15 percent) than the loss of ranch land (6 percent). Today, according to the California Department of Conservation’s Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program, 578,000 acres of important farmland and 1.7 million acres of grazing land remain in the region’s nine counties. While this represents a majority of the Bay Area’s land, historic trends of agricultural land loss may well continue unless action is taken. According to the Greenbelt Alliance, 15 percent of the region’s farmland and 7 percent of its grazing land is at either high or medium risk of development in the next 30 years (see our report Locally Nourished for more detail about this analysis). Every Bay Area county except San Francisco (for which data is not tracked by the state) has land at risk, but the areas with the highest concentrations are central Sonoma County, eastern Contra Costa County and southern Santa Clara County.

The historic trend and future risk of losing agricultural land to development is a result of the land’s proximity to existing development. High land prices at the urban edge make it difficult for a farmer to expand operations or for new farmers to enter the market in these areas. For example, in a 2011 study of the city of Morgan Hill, in southern Santa Clara County, a survey of real estate sales examined smaller parcels of land that were purchased for development and larger parcels that were sought for agricultural use. The parcels purchased for development commanded prices of $150,000 to $200,000 per acre, whereas the land purchased for agricultural use sold for $30,000 to $50,000 per acre.[5]

Figure 3: Farmland and grazing land is at risk across the Bay Area

While every county could lose farmland and grazing land, Sonoma, Santa Clara and Contra Costa have the greatest number of acres at risk in the next 30 years according to the Greenbelt Alliance. In total, 15 percent of the region’s farmland and 7 percent of its grazing land face significant development pressure.

Source: California Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program.

Preserving agricultural land in the face of this pressure requires a concerted effort by financial policymakers to support the economic viability of farms and ranches. A range of policy tools have been developed to support agriculture, and we discuss them in greater depth in the “Policy Tools for Agricultural Land Preservation on p. 10. These tools can help preserve not only the land itself but also the economic viability of agriculture. The most effective agricultural preservation policy recognizes, in the words of the American Farmland Trust, that “it’s not farmland without farmers.” In other words, farmers won’t continue farming if they can’t make a living doing it.

Policymakers in the Bay Area have a number of agricultural land preservation tools at their disposal. Recognizing that the economic and land use dynamics are different in each subregion, SPUR does not recommend a one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, each jurisdiction must design a suite of policies that best fits its situation.

Figure 4: At-risk agricultural land is most often at the edge of urbanized areas

The at-risk designation is based on the Greenbelt Alliance’s analysis comparing the threat of urban development with existing policy measures intended to preserve agricultural land in that area.

Source: Greenbelt Alliance analysis (2012) of California Farmland Mapping and Monitoring Program data (2010). San Francisco agricultural land analysis based on data collected for SPUR’s report Public Harvest (2012).

Agricultural land preservation serves not only to preserve farmland but also as a strategy to prevent sprawl — a long-standing goal for SPUR. We feel strongly that policies restricting development beyond the urban edge should be complemented by land use and transportation policies that support greater development and growth of already-urbanized areas, also known as infill development.

Jobs in the food system

In total, the Bay Area food economy provided 405,000 jobs throughout the nine counties in 2010, or one of every eight private sector jobs. Agricultural production of food, as critical as it is, represents only a small portion of those jobs (see Figure 5). Beyond the farms, processors and manufacturers turn raw vegetables into cut-and-packaged salad mix, fresh fruit into jam, milk into cheese and cattle into beef. Distributors broker raw and processed food between producers and retailers. Restaurateurs, caterers and grocers sell food to the public. And in more and more places, waste haulers turn food waste into compost that they in turn sell to farmers, thereby closing the food system loop.

Food sector employment has been increasing at a faster rate than private employment generally. Between 1990 and 2010, food sector employment increased by 21 percent, from 320,000 jobs to 390,000. In contrast, during that same time, private sector employment as a whole only increased by 4 percent.6 This employment growth, however, has not been evenly distributed among the food system sectors. While employment in the winemaking and waste sectors has increased by more than 80 percent each, jobs in food production and processing have decreased since 1990, though these declines appear to have leveled off in the past five years. Restaurant and food service employment has also seen robust growth of 38 percent in the past two decades.

Potential growth in the food economy

While recent employment trends are one indication of growth potential, a number of other trends indicate increasing demand for regionally produced food which could spur further growth. Farmers’ markets provide one indication. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the number of farmers’ markets nationally has been increasing since 1970 and has recently accelerated, going from 1,750 markets in 1994 to 7,864 markets in 2012.7 Additionally, the number of school districts operating local “farm-to-school” procurement programs across the country saw a 500 percent increase in recent years, going from 400 districts in 2004 to 2,100 districts in 2009.8 Within the restaurant sector, the majority of chefs in casual and fine dining restaurants surveyed in 2011 by the National Restaurant Assocation said they had seen increased interest in locally sourced menu items from their customers in the preceding two years and also reported that locally sourced meats, seafood and produce were the top trends in their restaurants.[9]

Figure 5: Distribution of food system jobs by sector

In total, the Bay Area food economy provided 405,000 jobs throughout the nine counties in 2010, or one of every eight private sector jobs. Within the food industry, the restaurants, food service and retail sectors provide nearly 80 percent of all Bay Area food system jobs. Within the processing sector, winemaking provides nearly half of all the employment.

Sources: California Regional Economies Employment (CREE) Series, California Employment Development Department (2010); U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Nonemployer Statistics

It is important to note that economic development includes not only the quantity of jobs but also their quality. Most food economy jobs — especially those in the production and food service sectors — offer low to modest wages.[10] Moreover, studies indicate that 12 percent of restaurant workers and between 25 and 50 percent of farmworkers are undocumented immigrants. According to the Food Chain Workers Alliance, “undocumented workers surveyed reported a median actual hourly wage of $7.60, compared to all other workers’ reported median hourly wage of $10,” indicating a wage gap based on immigration status.[11] While an increase in the quantity of jobs would help the Bay Area economy, the region’s residents would also benefit through an improvement in the quality of jobs in the food sector.

The economic benefits of sourcing locally

In addition to providing jobs and employment growth potential, a stronger regional food system provides economic benefit to the Bay Area by emphasizing local buying and selling rather than relying solely on imports and exports. When companies and consumers direct more of their dollars toward locally produced goods and services rather than counterparts from farther away they reduce the amount of money that leaks out of the Bay Area economy. As a result, more of the region’s wealth circulates locally, which produces the “local multiplier” effect. For example, assuming all other factors are equal, a Bay Area tomato sauce manufacturer will bring greater benefit to the region if it sources its tomatoes from Solano County rather than Mexico because the local tomato producer will spend a portion of what it receives locally (on wages, fertilizer and fuel, for example).

Numerous studies have documented the benefit of the local multiplier effect. An analysis of local retail in San Francisco — building off of earlier studies in Austin, Texas, and Chicago, Illinois — found that locally owned restaurants had a 27 to 30 percent greater positive economic impact on the local economy than a chain-owned restaurant, because more of the revenue and profit earned by the independent restaurants stayed local.[12] Similarly, a study conducted by the Union of Concerned Scientists concluded that farmers’ markets have a proportionally greater positive impact on local revenue and jobs than traditional grocery stores, even when accounting for a decrease in grocery sales resulting from the growth of the farmers’ markets.[13]

When businesses throughout the food system — ranging from producers to processors to retailers — prioritize local sourcing, the impact is even more pronounced. A study of the local food economy in Seattle found that spending at locally oriented food system businesses generated a greater multiplier effect than spending at those businesses that did not prioritize local sourcing. In the most pronounced example, grocery stores and restaurants that had a commitment to local purchasing had local multipliers twice as high as their conventional counterparts.[14] All of these studies indicate that strengthening our regional food economy, where local ownership and purchasing decisions are emphasized, provides economic benefits that are often lost when we import our food from farther away.

Located near Vacaville in Solano County, Jepson Prairie Organics is a large-scale composting facility owned by Recology, which provides waste management for San Francisco. The facility converts food and yard waste into high-quality compost that is sold to nearby farms. Photo by Larry Strong, courtesy of Recology.

While we seek to strengthen the food system across the Bay Area, we must also work to make sure its benefits are enjoyed equitably by people of all incomes. Currently, that’s not the case. According to Feeding America’s “Map the Meal Gap” project, in 2010 more than 1 million residents — or one in every seven people — across Bay Area counties met the USDA’s definition of “food insecure,” meaning that either the quality, variety and desirability of their meals were low or that they did not consistently have access to three meals a day.16 Increasing levels of food insecurity in the Bay Area, and the United States as a whole, reflect an increase in poverty that cannot be solved by looking at the food system in isolation from the larger economy. Food access is also a qualityof- life issue when residents have to travel long distances to purchase healthy food. And the growing public health concern over diet-related diseases also touches on food access — to both healthy and unhealthy food.

Numerous policy initiatives in recent years have sought to address issues of food access and affordability, such as the California FreshWorks Fund, Healthy Corner Store Network, California Farmers’ Market Consortium Market Match program and local campaigns to reform school meal programs. Some efforts focus on increasing the supply and availability of food, such as attracting food retailers to “food deserts,” improving the quality of food available at corner stores or expanding free and reduced-price breakfasts at schools. Others have focused on increasing demand, such as nutrition education programs or subsidies to consumers for the purchase of fresh food, or limiting access to unhealthy food, such as regulations regarding food sold in schools and other public facilities.

Researchers, policymakers and food system advocates should continue to pilot and evaluate various policy initiatives, and combinations of those initiatives, to better target their efforts to improve food security and food access.

One possible way to expand the benefits of the local multiplier effect is to make it easier to use food assistance programs, especially food stamps, to purchase local products. In the nine-county Bay Area, 430,000 residents — or 6 percent of the region’s residents — participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the federal food stamp program known in California as CalFresh, which is just one of the federal food assistance programs. Participating households receive an average of $332 per month, which is tens of millions of dollars in collective buying power.15 If more of these dollars could be used to purchase food from local producers — through farmers’ markets or other retail avenues — it could help expand the customer base for regionally grown products.

There are important limits to keep in mind in regard to the local multiplier effect, however. Consider the example of a farm-to-school procurement program. The local multiplier effect suggests that a school district could best support the economic well-being of its families by sourcing all of its ingredients from the region. However, if the district has to pay twice as much for local ingredients as it would for the equivalent from farther away, the district either receives half as much food or the bill is twice as high. With competing budget demands, those same dollars could be used to improve the school meals program in other ways, and the local procurement choice would be hard to justify. But if there is no price premium, or only a small premium, then the benefit to the local economy could very well justify a local preference. Determining the premium that is justified because of the local multiplier effect is a policy choice for local governments. It is also a topic that deserves its own in-depth research.

In short, the Bay Area’s food economy contributes to the diversity of the region’s overall economy and provides 12 percent of all private sector jobs. Rather than emphasizing food industry growth based on exporting food elsewhere, the region would also benefit from nurturing food industries that prioritize local sourcing and spending. The industries that make up the region’s food economy have room to grow in a way that benefits both rural and urban areas, especially if we are successful in preserving what remains of the region’s agricultural land.

Food waste and greenhouse gas emissions

A stronger regional food system offers not only the benefits of preserved agricultural land and economic development but also the potential for greater reduction of greenhouse gas emissions through food waste diversion. When food waste decomposes in a landfill, it releases methane, a greenhouse gas 21 times more potent than carbon dioxide. When food waste is composted, which is a different chemical process, it releases substantially fewer greenhouse gas emissions.17 This compost can then be beneficially reused as a soil amendment to improve agricultural soils.

Numerous Bay Area cities currently have food waste diversion programs. San Francisco, for example, has led the nation with its municipal composting program and diverts 300 tons of food waste daily, mostly to composting facilities in Vacaville, Modesto and Gilroy.[18] Food waste discarded in Berkeley is composted at a facility in Vernalis, in San Joaquin County.[19] The East Bay Municipal Utilities District, meanwhile, has a food waste digestion operation that generates electricity while processing food waste from nearby businesses in Alameda County. San Jose and the Central Marin Sanitation Agency are scheduled to begin using this model of food waste processing, called anaerobic digestion, in 2013.

While Bay Area municipalities are pioneers in food waste diversion, there is still much more to be done. SPUR estimates that the Bay Area sends more than 970,000 tons of food waste to landfills each year. If all of this food waste were sent to compost facilities instead, carbon dioxide equivalent emissions would fall by at least 863,000 metric tons -- the same impact as taking 163,000 cars off the road for a year or reducing the region’s waste management facilities emissions by 44 percent.[20]

A regional food system that utilizes composting and other food waste diversion methods, as the Bay Area has begun to do, helps reduce the region’s carbon footprint and closes the resource loop by turning food waste into compost that supports food production.

By strengthening the regional food system, the Bay Area has an opportunity to capture more of the land use, economic and environmental benefits the food system provides while also preserving the 15 percent of the region’s agricultural land that is currently at risk of being developed in the next 30 years. The region’s diversity of land use patterns, existing food infrastructure and jurisdictions requires a diversity of approaches. Few of the recommendations below can be executed in a one-size-fits-all fashion. Instead, each jurisdiction or agency will need to tailor the implementation to its specific context. A more in-depth exploration of each of these recommendations is included in our full report, available at spur.org/locallynourished.

We recommend that boards of supervisors should:

Local food systems are often credited with reducing carbon emissions by reducing the distance — or “food miles” — that products travel from farm to fork. Intuitively, this makes sense. If all factors of production and distribution were the same, an apple from Sonoma County, for instance, would have a lower carbon footprint than an apple from Washington State or New Zealand because of its proximity to the Bay Area. Empirically, however, there is insufficient data to support a consistent correlation between the full carbon footprint of food and how many miles it travels to get to the consumer’s table. This is because the factors of production — such as fertilizer application and soil management — are not always equal. And, importantly, the production of food accounts for more than 80 percent of the carbon footprint of the average food item, while the transportation involved in the final delivery of the food to retail consumers ranges from 1 to 11 percent depending on the type of food and mode of transportation.[21] In other words, how food is produced has a much greater influence on its carbon footprint than where it is produced. A U.S. Department of Agriculture study similarly concluded that food miles were not a valid proxy for food’s overall carbon footprint.[22]

There is, however, data to support the environmental benefit of certified organic and sustainable farming methods in contrast with “conventional” methods. A survey of the literature regarding diversified farming systems — as opposed to industrial farms with single crops — showed that these agricultural practices consistently provided better soil management, carbon sequestration potential, weed control, biodiversity and more efficient energy use.[23] Similarly, a National Academy of Sciences study concluded that while there are many challenges to expanding sustainable agricultural practices, the benefits to the environment and society are numerous.[24]

County and city planning departments and city councils should:

The Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) should:

City and county economic development agencies, in partnership with food industry trade groups, should:

Public procurement offices should:

County social services agencies should:

County and city waste management authorities should:

USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service, Resource Conservation Districts, UC Cooperative Extension and county agricultural commissioners should:

Cities and counties throughout the region have begun taking action on agricultural land preservation, food industry economic development and reducing the environmental impact of the food system. But to truly meet the challenge and take advantage of the opportunity facing the Bay Area, policymakers at the city, county and regional level must build upon and accelerate their efforts.

This article is excerpted from the SPUR report "Locally Nourished." Read the complete report at spur.org/locallynourished >>

--

Endnotes:

[1] Other studies have been used alternative definitions for the region or its “foodshed,” such as a radius of 100 miles from the Golden Gate.

[2] For example, SPUR was a lead supporter of the establishment of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area in the early 1970s. See www.spur.org/publications/library/article/establishingGGNRA05011999

[3] University of California, Davis and the California Energy Commission, Adaptation Strategies for Agricultural Sustainability in Yolo County, California (July 2012), 140–167.

[4] For a more in-depth, county-by-county analysis, see Sibella Kraus, Kathryn Lyddan, Jeremy Madsen, Edward Thompson and Serena Unger, Sustaining Our Agricultural Bounty: An Assessment of the Current State of Farming and Ranching in the San Francisco Bay Area (American Farmland Trust, Greenbelt Alliance, Sustainable Agriculture Education, January 2011).

[5] Economic and Planning Systems, Inc. and House Agricultural Consultants, Morgan Hill Agricultural Policies and Implementation Program (December 2011), 11.

[6] This analysis of employment trends over time does not include non-employer data.

[7] USDA Agricultural Marketing Service, “Farmers Market Growth: 1994–2012,” www.ams.usda.gov/

[8] Steve Martinez et al., Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues (Economic Research Report Number 97, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, May 2010), 5–6 and 14–15.

[9] National Restaurant Association, “2012 Restaurant Industry Forecast” (2012), www.pma.com; National Restaurant Association, “What’s Hot 2013 Chef Survey,” https://restaurant.org/News-Research/Research/What-s-Hot

[10] Collaborative Economics, The Food Chain Cluster: Integrating the Food Chain in Solano and Yolo Counties to Create Economic Opportunity and Jobs (May 2011), 13; Food Chain Workers Alliance, The Hands that Feed Us: Challenges and Opportunities for Workers Along the Food Chain (June 2012), 16–20.

[11] Food Chain Workers Alliance, The Hands That Feed Us, 21, 34, 43.

[12] Civic Economics, The San Francisco Retail Diversity Study (2007), 2, 20.

[13] Jeffrey O’Hara, Market Forces: Creating Jobs Through Public Investments in Local and Regional Food Systems (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2011), 18.

[14] Viki Sonntag, Why Local Linkages Matter: Findings From the Local Food Economy Study (Sustainable Seattle, 2008), 18–19.

[15] Tia Shimada, California Food Policy Advocates, Lost Dollars, Empty Plates (2013), 9–10, http:// cfpa.net/CalFresh/CFPAPublications/LDEPFullReport-2013.pdf.

[16] Feeding America, Map the Meal Gap, Food Insecurity in Your County, http://feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/hunger-studies/map-themeal-…; USDA definition of food insecurity: USDA Economic Research Service, “Definitions of Food Security,” www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-…. See also M. Pia Chaparro et al., Nearly Four Million Californians Are Food Insecure (UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, 2012), http://cfpa.net/foodinsecurity2012

[17] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10, Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions Through Recycling and Composting (May 2011), www.epa.gov

[18] Interview with Robert Reed, public relations manager, Recology, April 2013. See also Dan Sullivan, “Food Waste Critical to San Francisco’s High Diversion,” BioCycle Magazine (September 2011), www.biocycle.net/2011/09/web-extra-foodwaste-critical-to-san-franciscos…

[19] Amy Kiser, “Compost Confidential,” Terrain (Spring 2010).

[20] For waste and emission equivalency calculations, see our report Locally Nourished. Regional waste management facilities emissions from Bay Area Air Quality Management District, Source Inventory of Bay Area Greenhouse Gas Emissions (December 2008), 19.

[21] Christopher L. Weber and H. Scott Matthews, “Food Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States,” Environmental Science and Technology 42, no. 10 (2008), 3508– 3513. See also Sarah DeWeerdt, “Is Local Food Better?,” World Watch Institute Magazine (May/ June 2009), www.worldwatch.org/node/6064; Tara Garnett, “Where Are the Best Opportunities for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the Food System (Including the Food Chain)?,” Food Policy 36 (2011), S23–S32.

[22] Steve Martinez et al., “Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues,” 48–49.

[23] Claire Kremen and Albie Miles, “Ecosystem Services in Biologically Diversified Versus Conventional Farming Systems: Benefits, Externalities and Trade-Offs,” Ecology and Society 17, no. 4 (2012), 40, www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol17/iss4/art40

[24] Committee on Twenty-First Century Systems Agriculture, Toward Sustainable Agricultural Systems in the 21st Century (National Research Council of the National Academies, 2010), 519–533, www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12832