This article is excerpted from the SPUR report Safe Enough to Stay. Read the complete report at spur.org/safe-enough >>

When a major earthquake strikes the Bay Area, the region could face thousands of casualties, hundreds of thousands of displaced households and losses in the hundreds of billion dollars. The lives of San Franciscans will be enormously disrupted, and it could take months to re-establish essential services. Recovery will be slow, depending on the extent of the building damage, the amount of business lost, the availability of utilities and how quickly communities can repair and rebuild their housing.

In order to rebound quickly after a major earthquake, San Francisco needs to become a resilient city. Resilience is the ability of the city to contain the effects of earthquakes when they occur, to carry out recovery activities in ways that minimize social disruption and to rebuild in ways that mitigate the effects of future earthquakes. The more quickly a community is able to rebound from a major event, the more resilient it is.

This article, based on our report Safe Enough to Stay, addresses one consideration: housing. After a major earthquake hits, how many San Franciscans will be able to shelter in place, i.e., stay in their homes while those homes are being repaired? What does it mean for the city’s overall resilience if some neighborhoods suffer more damage than others? What steps can city government, building owners and residents take now to ensure that homes are safe to occupy after an earthquake strikes?

Housing is only one element in the complex web of factors that contribute to the city’s earthquake resilience, but we believe it is an especially important one. Housing is linked to every other aspect of the city’s recovery: Businesses, neighborhood districts, schools and cultural institutions all rely on residents being in the city. If people can stay in their homes, they will be more able to put their energy and resources into rebuilding their neighborhoods. If they must leave the city, their resources will go with them, perhaps permanently.

In this article, we answer the following questions:

1. How much of San Francisco’s housing stock needs to meet shelter-in-place standards in order for the city to be resilient?

2. What engineering criteria should be used to determine whether a home has shelter-in-place capacity that's adequate for a major earthquake?

3. What needs to be done to enable residents to shelter in place for days and months after a large earthquake?

I. How much of San Francisco’s housing stock needs to meet shelter-in-place standards in order for the city to be resilient?

The question of how much housing in a city can be damaged by an earthquake before the city’s viability is undermined is not easily answered. However, after assessing the city’s existing capacity for short-term housing (shelter beds) and medium-term or “interim” housing (hotel rooms, trailers) and analyzing how housing damage in recent relevant disasters affected community resilience, we conclude that 95 percent is an appropriate goal.

San Francisco’s emergency and interim housing capacity

After a magnitude 7.2 earthquake on the San Andreas Fault (see "Defining the Expected Earthquake" on page 8 for more on why we use this metric), approximately 85,000 households (roughly 25 percent of San Francisco’s population [1]) could need interim housing for several months, gradually decreasing to 45,000 households (approximately 13 percent) by two years after the earthquake. Up to 15,000 households (approximately 5 percent) could require interim housing for up to five years. [2]

San Francisco’s Department of Emergency Management estimates that its top shelter capacity is 60,000 persons, or roughly 7.5 percent of San Francisco’s overall population. Sheltering this many people would require maximizing shelter space at large convention facilities like the Moscone Center and also making use of some outdoor or soft-sided shelters to supplement indoor space. If we were only to use indoor facilities, capacity would be reduced to 45,000 persons, or roughly 5.5 percent of San Francisco’s population. [3]

After the emergency period has subsided, residents will need to find interim housing during the period when repairs to damaged housing are being completed and new replacement housing is constructed. San Francisco’s options for providing interim housing are severely constrained and could lead to residents being dispersed to other parts of the state (or possibly even farther).

Recent comparable disasters

Perhaps the best way to investigate whether a goal of 95 percent shelter in place is reasonable for San Francisco is to consider how other communities fared after major disasters (See Figure B). Several relevant lessons for San Francisco emerge from the experiences of disasters in other communities:

1. Rebuilding housing takes a long time, even if the percentage of units rendered uninhabitable is relatively small. It took at least two years for a significant portion of housing to be replaced in all of the profiled disasters for which information was available. After the 1995 earthquake in Kobe, Japan — an area often cited as similar to the Bay Area — it took the city five to 10 years to reach its rebuilding goals.

2. Multifamily and affordable housing is much more difficult and slower to replace than single-family, market-rate housing. Financing and legal issues are some of the many factors that slow down this work. After the Bay Area’s Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, it took seven to 10 years to replace all of the damaged affordable housing. If affordable housing is lost, it is possible that some might never be replaced, leading to a significant shift in post-event population.

3. Large losses of housing lead to permanent losses of population. Hurricane Katrina and the Kobe earthquake had housing losses greater than 25 percent. Both events caused large population losses and demographic shifts. Even where housing losses were much smaller — such as the Christchurch earthquakes in New Zealand — large losses in population were felt.

4. Interim housing matters. After the 1994 Northridge earthquake in Los Angeles, most of the people displaced were able to relocate nearby due to the area’s pre-earthquake 9.3 percent vacancy rate. Vacant rental units served as interim housing. In San Francisco, the vacancy rate is typically much tighter, currently 4 percent,[4] meaning the city will need more active measures to house its displaced residents over longer periods.

We believe that San Francisco would experience significant consequences if even only 5 percent of its housing units were unusable after an earthquake, given the city’s low vacancy rates, density and limited capacity for interim housing. If more housing were damaged, the potential social and economic consequences could be devastating.

What Does It Mean to Shelter in Place?

SPUR defines “shelter in place” as a resident’s ability to remain in his or her home while it is being repaired after an earthquake — not just for hours or days after an event, but for the months it may take to get back to normal. For a building to have shelter-in-place capacity, it must be strong enough to withstand a major earthquake without substantial structural damage. This is a different standard than that employed by the current building code, which promises only that a building meets life-safety standards, that is, the building will not collapse but may be so damaged as to be unusable. A shelter-in-place residence will not be fully functional, like a hospital would need to be, but it will be safe enough for people to live in it during the months after an earthquake. While utilities such as water and sewer lines are being repaired and reconnected, residents who are sheltering in place will need to be within walking distance of a neighborhood center that can help meet basic needs not available within their homes.

How will San Francisco’s neighborhoods be impacted by the expected earthquake?

After a magnitude 7.2 earthquake on the San Andreas Fault, approximately 25 percent of San Francisco’s housing units would be unsafe for residents to occupy. In other words, we currently expect 75 percent of residences to be available for sheltering in place after the expected earthquake.

SPUR has refined estimates of housing damage provided by the Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety (CAPSS) so that they could be reported in greater detail by neighborhood and structure type.[5] The analysis makes clear that housing in every San Francisco neighborhood would be damaged heavily by the expected earthquake. The neighborhoods that will see the most damage are those with large amounts of multifamily housing, which is generally more vulnerable than smaller residences, and those that have significant areas of soft or liquefiable soils, which can experience magnified shaking and ground failure.

Defining the Expected Earthquake

For the purposes of defining resilience and developing mitigation policies to achieve it, SPUR uses one of the scenario earthquakes developed by the Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety (CAPSS): a magnitude 7.2 earthquake on the peninsula segment of the San Andreas Fault.

We refer to this scenario as the “expected earthquake” because an event of this magnitude can be expected — conservatively but reasonably — to occur once during the useful life of a structure or system, and more frequently if the structure is renovated to serve more than one or two generations.

SPUR's Recommendations

1. Adopt recovery targets for the housing sector as a whole, based on what is necessary for citywide resilience in a large but expected earthquake.

SPUR recommends 95 percent shelter in place as the appropriate goal for San Francisco. This target should be adopted by the City and County of San Francisco, either in the Community Safety Element of the General Plan or as a stand-alone piece of legislation adopted by the Board of Supervisors. The city should set a 30-year time frame to reach this goal, mirroring the 30-year time frame identified to implement the CAPSS recommendations.

2. Implement the Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety (CAPSS) recommended mandatory soft-story retrofit program.

Estimated increase in shelter-in-place capacity:

5–6 percent

As SPUR noted in its 2009 resilient city report, the single most important step San Francisco can take to increase its resilience is to adopt a mandatory retrofit program for wood-frame soft-story buildings with three stories or more and five units or more. If these buildings were seismically retrofitted, we estimate that 80 percent of city residents would be able to shelter in place after the expected earthquake.[6]

3. Develop soft-story retrofit program for smaller soft-story buildings.

Estimated increase in shelter-in-place capacity:

6–9 percent

Smaller wood-frame soft-story buildings also pose a major challenge to San Francisco’s resilience. These buildings are represented in large numbers in the Sunset and Richmond districts, both of which are highly vulnerable to the expected earthquake. A retrofit program is needed for these buildings as well.

4. Develop retrofit programs for other vulnerable housing types that impact San Francisco’s resilience and also have the potential to severely injure or kill people.

Estimated increase in shelter-in-place capacity:

1 percent

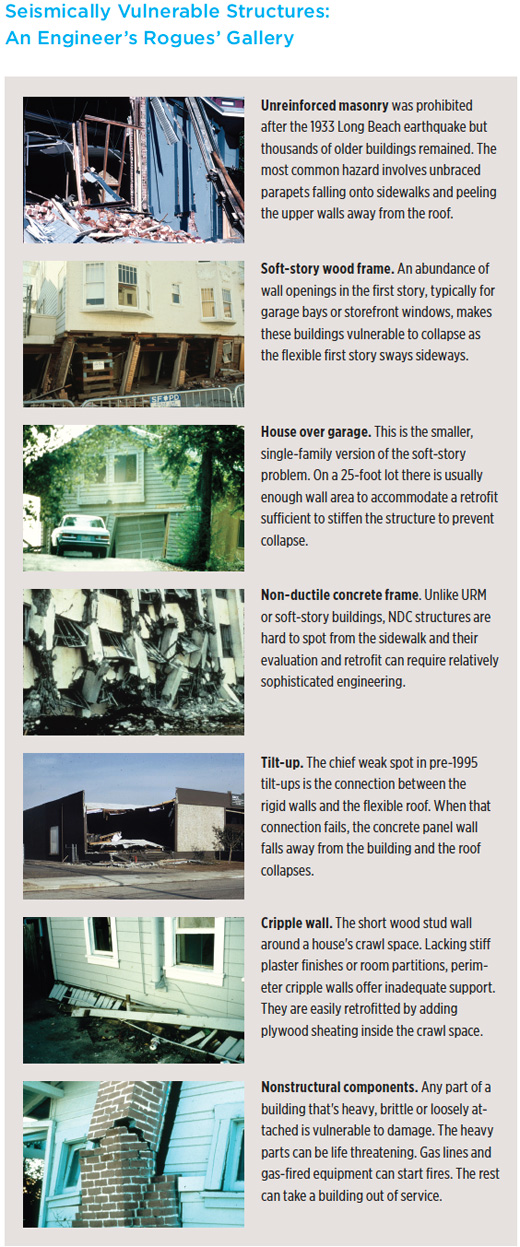

There are a number of building types used for housing, such as non-ductile concrete buildings and unreinforced masonry buildings, that will not serve as shelter-in-place housing and also have the potential to be significantly damaged, causing injury and significant loss of life. As we do not currently know how many of these buildings exist, the city should begin by developing a reliable inventory of them.

5. Focus on developing an interim housing strategy for San Francisco.

The city should complete its interim housing planning process and adhere to its objectives to keep as many residents as possible in their homes; keep residents within their neighborhoods; keep people within the city; and finally, if residents are relocated, have a plan to bring them back.

II. What engineering criteria should be used to determine whether a home has adequate shelter-in-place capacity?

While shelter-in-place capacity is needed after the earthquake, the ability to assess an individual building’s expected performance is needed beforehand.

SPUR recognizes that San Francisco’s resilience requires more than basic safety during the earthquake. It requires that buildings remain habitable and repairable so that occupants can live safely in them even before repairs begin.

To support the move to resilience-based earthquake planning, the city’s existing structural-evaluation criteria need to be revisited. Specifically, the city needs to determine what shelter in place means from an engineering perspective and to develop a criteria for analyzing now, before the earthquake, whether a building is likely to serve as shelter-in-place housing afterward.

We recommend that feasible shelter-in-place evaluation criteria be based on existing standards already familiar to practicing engineers and code officials. Those standards should account for:

> Cost-effective procedures;

> The range of residential structure types in San Francisco;

> Differences between new and existing structures (unlike most building code provisions); and

> Nonstructural conditions that affect shelter-in-place habitability.

We recommend the use of the national standard called Seismic Evaluation of Existing Buildings,[7] also known as ASCE 31.

To determine whether a building has shelter-in-place capacity, the ASCE 31 criteria should be modified to consider only the types of damage that are critical for sheltering in place with reference to approved maps of relevant hazards and expected infrastructure performance.

SPUR's Recommendations

6. Further develop shelter-in-place evaluation criteria for voluntary, mandatory and triggered seismic work on residential buildings.

We have described one approach to developing shelter-in-place evaluation criteria. However, much work is yet to be done. SPUR recommends that the Office of the City Administrator, the Department of Building Inspection and the Department of Emergency Management further develop shelter-in-place evaluation criteria.

7. As draft criteria are developed, generate a new loss estimate for the magnitude 7.2 San Andreas and other scenario earthquakes.

Our best estimate of housing loss and its impact on recovery (based on the CAPSS data referenced above) does not account specifically for what we have now defined as shelter-in-place performance. With the new definition in place, and with draft engineering criteria in progress, the Department of Building Inspection and the Department of Emergency Management should undertake a new loss estimate focused on shelter-in-place performance.

III. What needs to be done to enable residents to shelter in place for days and months after a large earthquake?

SPUR believes it is critical to define alternative shelter-in-place housing standards that are safe enough to allow people to stay in their homes but not so stringent that otherwise safe buildings will be deemed unsuitable for occupancy. How do we set a post-earthquake standard that is “safe enough”? We need to define alternative standards that would supersede regular code requirements and standards during a housing-emergency period declared by the city after a major earthquake. Such an emergency period might extend for days, weeks or longer.

Shelter-in-place standards should be phased, with the expectation that repairs need to be made over time to restore habitability. Certain standards that would be considered acceptable immediately following the earthquake (such as using portable outdoor toilets) would not be considered acceptable three months after the earthquake. The shelter-in-place standards should define which needs will be met by the building itself and which will be met outside the building for each time phase. Those resources that must be met outside the building will need to be provided at a neighborhood service center located in close proximity to shelter-in-place housing.

Figure C

Phased Habitability Standards Following an Earthquake

After an earthquake, even housing that is safe enough to occupy will not meet existing codes. A phased standard needs to be defined in this post-earthquake period.

Figure C illustrates the idea of alternative habitability standards that would apply in emergencies but gradually revert to normal code requirements. The blue line represents the code standards for habit-ability that normally apply. When an earthquake occurs, some damage might result, but if the damage is light, it would not affect the city’s overall resilience, so no relaxation of the normal standards would be justified. A declared housing emergency, however, indicates that damage — and possibly housing loss — is significant enough to justify special measures to speed response and recovery. The red line represents the minimum standard to be met within a residence. The pink shaded area represents elements that will be provided outside of the home by a neighborhood service center. The red shaded area represents the actual loss of habitable housing. As repairs are made, the loss is recovered, and buildings return to normal.

Minimum habitability requirements for occupancy after the earthquake

SPUR has identified five different post-earthquake time periods and defined the major habitability requirements for each:

1. The immediate post-earthquake period

2. One week after the earthquake

3. One month after the earthquake

4. Three months after the earthquake

5. After the declared housing emergency is over

Increasingly robust habitability standards will need to be met in each phase, as described in Figure D.

Building evaluation and inspection

After a major earthquake, engineers and design professionals come from all over the country to help conduct formal building inspections using what is known as the ATC-20 evaluation procedure. They evaluate building structures and tag them depending on their level of damage: Red tags mean a building is unsafe and should not be entered or occupied; yellow tags indicate restricted use, meaning a building either requires further evaluation or is okay to occupy except for designated areas; and green tags mean that no unsafe conditions were found or suspected.

Shelter-in-place evaluations are not a building tagging program. Instead, they will provide immediate guidance for residents as to whether nonstructural and related conditions are suitable for continued occupancy. Residents will need to review shelter-in-place conditions within 24 hours of an earthquake so that they know whether they can remain in their homes. Meanwhile, it may take a period of several days or weeks for inspectors and design professionals to undertake ATC-20 evaluations.

Shelter-in-place standards need to be clear enough so that most residents will be able to assess their own buildings. But many residents will need help and guidance in applying shelter-in-place standards to their buildings while they wait for design professionals to complete an ATC-20 evaluation. Private community volunteers can be trained to help residents determine if shelter-in-place standards are met.

SPUR's Recommendations

A post-earthquake alternative shelter-in-place habitability standard should be established and implemented in order to encourage residents to remain in their homes. The following recommendations will help to achieve this goal.

8. Create a San Francisco interdepartmental shelter-in-place task force.

The Mayor’s Office should create an interdepartmental task force that will ensure coordination with the Department of Building Inspection, the San Francisco Fire Department, the Department of Public Health and the Department of Emergency Management. Other agencies to be involved should include the Department of Public Works, the Mayor’s Office on Disability, the Mayor’s Office on Housing and others.

9. Prepare and adopt regulations that allow for the use of shelter-in-place habitability standards in a declared housing-emergency period.

Shelter-in-place standards may be adopted in advance of an emergency or be completed and ready to adopt as part of the city’s emergency measures. Administrative bulletins and similar regulations should be adopted by various agencies to detail how code requirements and policies will need to be implemented. These should include complaint, inspection and enforcement procedures.

During a declared emergency, a separate housing emergency may also be declared, which would allow the enforcement of the alternative shelter-in-place habitability standards. A declared housing emergency may continue as a special emergency period past the general declared emergency period and may be applied to specific areas where housing is most severely impacted.

10. Develop a plan for implementation of a shelter-in-place program.

This implementation plan should include the creation of public training materials, coordination with existing post-disaster building evaluation procedures and the stockpiling of materials needed to achieve shelter in place in the post-disaster period.

A. Preparation of public training materials

The interagency task force recommended above should develop simple and clear training materials for residents to help them determine whether or not they can shelter in place. These should include a set of graphic illustrations and a shelter-in-place checklist, which should be incorporated in outreach and training materials to building owners and residents to inform them of shelter-in-place habitability requirements, standards, inspection procedures and repair expectations. These could include such elements as door tags that say “I’m OK!” or “I Need Help.” Additionally, residents could receive special training in shelter in place prior to an event, much like the current Neighborhood Emergency Response Team (NERT) program.

B. Coordination with existing post-disaster evaluation procedures

After an earthquake, professionals will come from all over the country to help evaluate buildings using the ATC-20 evaluation procedure. If San Francisco’s evaluation procedures are modified to focus on shelter in place, ATC-20 inspectors will need to be trained in San Francisco–based shelter-in-place habitability standards.

C. Storing materials necessary to allow shelter-in-place standards to be met

The city will need to have certain materials, such as plastic sheeting for weather protection, on hand for use after a major earthquake. SPUR recommends that the Department of Building Inspection, the Department of Emergency Management and the Department of Public Health coordinate to develop a list of these materials and the quantities that will be needed.

11.Develop plans for neighborhood support centers to provide necessary support for shelter-in-place communities.

Neighborhood support centers are not emergency shelters. Rather, they are resource centers near residences that support and encourage people to stay in their homes by providing essential services and information and ensuring that the balance of human needs, outside the shelter-in-place home, is met. A store, restaurant, small business or religious or social facility could provide necessary local space. A large garage or other covered area could be equipped to provide these services. Neighborhood support centers will need to be staffed and equipped to provide information and services such as distribution of supplies, water and food; and referrals to community service organizations and agencies.

The Path to Resilience

It is hard to plan for the unknown. We know that future earthquakes will damage the Bay Area, but we don’t know where, when or how large these earthquakes will be. But there are things that San Francisco can do now to help its buildings survive the expected earthquake and enable its residents to stay and rebuild their homes.

The steps we propose aren’t easy. They require money, political capital and coordination among many public agencies. Yet the risk of doing nothing is enormous. If San Francisco does not take the steps outlined in this report, the city will need to find ways to provide interim housing for approximately 85,000 households — roughly 25 percent of its population. There are not nearly enough shelter beds and interim housing capacity to meet this demand. San Franciscans need to be able to shelter in place.

Through a combination of retrofits and careful planning we can make San Francisco’s housing safe enough to stay. It won’t happen overnight. But if we don’t begin work now, we won’t be ready when the next large earthquake strikes. SPUR believes that is a risk too great to take.

--

[1] There are approximately 330,000 households in San Francisco. The estimate of 85,000 households comes from analysis of CAPSS HAZUS output data — see Figure B.

[2] Laurie Johnson and Lucas Eckroad, “Summary Report on the City and County of San Francisco’s Post-Disaster Interim Housing Policy Planning Workshop,” July 11, 2001, San Francisco Department of Emergency Management.

[3] E-mail correspondence with Robert Stengel, Department of Emergency Management, September 1, 2011.

[4] Vacancy rates in SF are currently 4% and are continuing to tighten due to high demand from growing employment sectors, potentially exacerbating interim housing needs should a disaster strike. First quarter 2011. Data from Reis, Inc. as quoted in “U.S. Housing Market Conditions: Pacific Regional Report, HUD Region IX – 1st Quarter 2011.” Available at www.huduser.org/portal/regional.html.

[5] Defining building performance in terms of shelter in place is a new concept. The CAPSS project used the best information and methods available at the time to estimate the amount of housing that would be usable after an earthquake. This task force has now developed improved methods to identify which residences could be used to shelter in place, but this new approach has not yet been applied to San Francisco’s building stock. The analysis presented in this report is based on the CAPSS analysis. We are hopeful that an improved analysis will be conducted sometime in the future using the methods developed by this task force, producing updated and refined estimates of housing damage.

[6] This assumes a high standard of retrofit, referred to as Retrofit Scheme 3 in the CAPSS report “Here Today — Here Tomorrow: Earthquake Safety for Soft-Story Buildings” (ATC 52-3). There are 4,400 wood-frame buildings with three or more stories and five or more units in San Francisco, an unknown number of which have a soft-story condition.

[7] ASCE 2003