Shanghai’s old town — the Chinese City — is today considered a slum. The compact low-rise neighborhood in downtown occupies 1/3,000th of metropolitan Shanghai. Most lanes are too narrow for cars, and half the housing stock is makeshift. It’s an embarrassment to locals and a little baffling to visitors.

For seven hundred years this was all of Shanghai. It was hardly a slum. The city was a magnet for sea merchants, agribusiness and gentry from throughout eastern China. A surrounding wall guaranteed Shanghai’s security and prosperity. In 1843, Chinese ports were forcibly opened to foreign trade. The old town’s autonomy set it apart from the rising colonial city just outside the wall — and this segregation led to its economic decline as modern Shanghai flourished. But cohesion and isolation preserved the old town. Artifacts and architectural styles from the Ming to the present are still embedded in the fabric of the alleys. The old town is authentically mixed-use and polymorphous: generations of residents, artisans, tiny businesses and antiquities are enfolded within the membrane of its lanes.

The old town’s rustic character is unique for being so central. But its location is

hazardous. Government developers have a financial stake in evicting the poor and

reintegrating the old town into the traffic flow of the surrounding city. Success for the

planners will be the death of the old town. But for the present, one can still meander

across the old Shanghai and experience distinct overlapping eras. Our attraction to

this archaic and quirky neighborhood turned into an ongoing (or interminable) photographic project.

City Labyrinth. Interaction between street, trade and social network stretches back

centuries. There’s a world of activity here: produce stalls, snack carts, improvised

markets and family stores. Recyclers pedal their carts to the sound of a cracked bell;

neighbors play cards or barter fighting crickets; families chat across the balconies, wash vegetables in the communal sinks or simply lounge in the alleys.

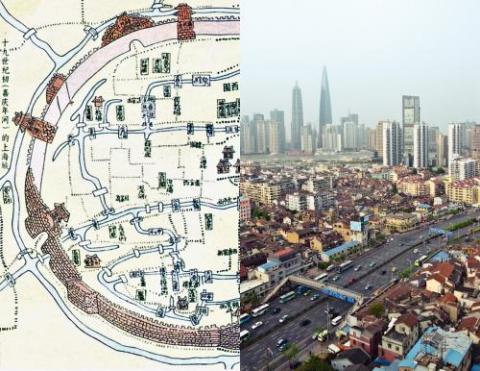

Creeks and Lanes. Fuxing Road is a 10- lane highway dividing the old town. It used to be a waterway running across the city west to east. A tapestry of creeks defined the original contours of Shanghai, providing portage for river traders and irrigation for farms. As the population grew, creeks were filled and became lanes. Map courtesy virtualshanghai.com.

Merchant City of the Qing. Merchants from Canton, Fujian and Ningbo immigrated to Shanghai for the exploding river trade in the 1800s. They built community centers (huiguans) that served as banquet halls, temples, brothels, theaters, hotels and

graveyards. Zhening Guild Hall, 1850, was converted to a factory in the 1960s.

Lane Houses. Shanghai’s vernacular residences are lilongs: two-story units aligned in rows branching out from a main lane. Originally built as cheap tract homes, lilongs became Shanghai’s most quintessential and prized architecture. They were intended for one family, but today dozens of people live in each lane house.

The Gardens of the Ming. In the 16th century, Shanghai eclipsed Suzhou as a trading and cultural center. Landed gentry competed to build showpiece mansions. The Secret Library (“Shu Yin Lou”) was part of a famous garden owned by an imperial scholar. It’s the oldest residence in Shanghai, still occupied, and it’s a ruin. The government will not restore or maintain the property while it’s in private hands.

Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Red Guards scrubbed off old signs, vandalized homes, burned wooden temples, razed old gardens and built pig-iron workshops in their place. Slogans and red icons were

scrawled on every wall.

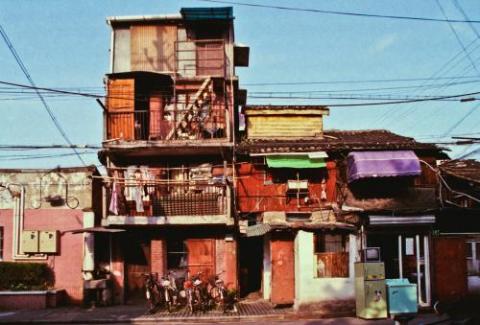

Liberation Sheds. Communist Shanghai put the knife in new architecture,

but there was a blizzard of quick modifications. Private houses were opened

to the masses. Large buildings were subdivided and haphazardly expanded.

Here, extra floors are slapped on a wooden tenement.

Capitalist Endgame. Contemporary plans for the old town involve eradicating old

housing, carving new traffic channels and constructing an antiquity flavored theme

park along the riverside. Current residents will be relocated to tenements in the suburbs.