Oakland neighborhoods like Temescal and Rockridge are walkable, have great restaurants, parks and transit access — and are too expensive for most. These neighborhoods would be great places to build the city’s needed housing, but many have zoning regulations that prevent it. At a recent SPUR forum, panelists discussed the ways in which well-established neighborhoods like Rockridge can accommodate more housing. Robert Gammon of Oakland Magazine, Justin Horner of East Bay Forward and Loni Gray of All Things Housing offered three key lessons for Rockridge and other neighborhoods in the region:

1. Zoning has a powerful effect on housing equity and on efforts to address the housing shortage.

The physical design of neighborhoods — and the zoning rules that dictate it — has an enormous effect on the way a community looks and feels, and on who can live there. Robert Gammon described how many Bay Area neighborhoods like Rockridge have a zoning history rooted in racism: Early 1900s developers attached racially restrictive covenants to the deeds of homes and used exclusionary zoning ordinances to ban people of color from white neighborhoods. Subsequent zoning changes set building height limits and parking requirements to make apartment buildings (an affordable housing option for many low-income people) illegal in neighborhoods throughout Berkeley and Oakland.

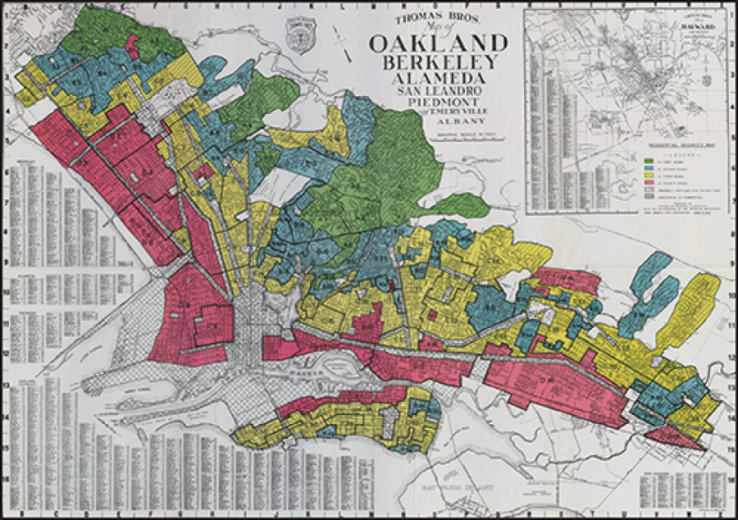

This 1937 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Oakland labeled neighborhoods from A (“best”) to D (“hazardous”) for underwriting mortgages, based on their racial makeup. Maps like these codified racial segregation, and new research shows that their effects have lasted for generations. Image courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Mapping Inequality.

This 1937 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Oakland labeled neighborhoods from A (“best”) to D (“hazardous”) for underwriting mortgages, based on their racial makeup. Maps like these codified racial segregation, and new research shows that their effects have lasted for generations. Image courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Mapping Inequality.Today, low-density zoning in neighborhoods like Rockridge hurts our ability to address the housing shortage — for everyone. Gammon emphasized that preventing or opposing housing in some Oakland neighborhoods concentrates development into a few areas — mostly downtown and uptown — and then exacerbates gentrification and displacement there. The more neighborhoods taking responsibility for the city’s housing need, the better.

2. Many neighborhoods that are currently zoned for a lower density weren’t always that way, and now access to transit make them even better places for more housing.

Though zoned for almost all single-family homes today, Rockridge is dotted with small apartment buildings of up to 10 units that were built in the 1920s and ’30s. Planners refer to this housing type as the “missing middle” in the current housing market. Very little of it has been built in recent decades because of restrictive zoning, incentivized single-family home ownership and the shift to building car-dependent cities. Missing middle housing could support a diverse range of households and increase density, all while blending into a lower density neighborhood — but it’s now illegal to build in Rockridge and other established neighborhoods.

Rockridge is also a transit-rich neighborhood — a BART rider can be in downtown San Francisco in just 25 minutes — and corridors like College Avenue are great places to add housing at higher densities. Justin Horner and East Bay Forward advocate for a return to building both single and multi-family housing in the same neighborhoods, as well as for higher density development near transit stations.

3. We can be creative about solutions to restrictive zoning in neighborhoods like Rockridge.

Zoning changes that allow small apartment buildings and other missing middle housing aren’t the only solution for neighborhoods like Rockridge. Design firms like All Things Housing remodel single-family homes throughout Oakland to create separate spaces or units to accommodate residents’ needs: Some are homeowners looking for secondary income through rent, others include a divorced couple hoping to raise their children together while maintaining independence. Adding a second housing unit (also called an in-law unit, granny flat, accessory dwelling unit or ADU) can also help add density to established neighborhoods. State law passed in January of this year aims to streamline the permitting process and reduce barriers to building these units, such as parking requirements or costly utility hookup fees. Though the law is great news for this type of housing, local zoning codes still restrict single-family home remodels and other creative solutions.

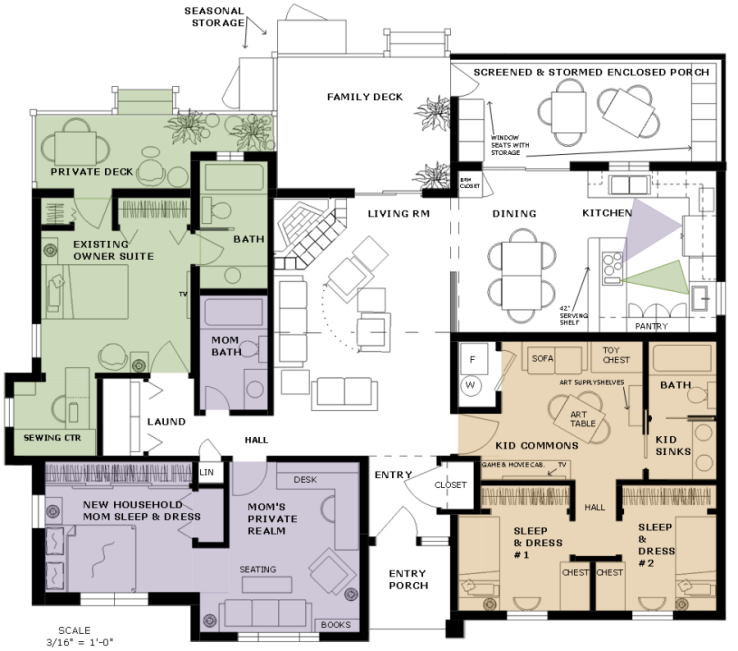

This redesign of a single-family home now accommodates the original homeowner and a single mother with two children, with private realms arranged around common space. Courtesy of Loni Gray, All Things Housing ©2017 All rights reserved.

This redesign of a single-family home now accommodates the original homeowner and a single mother with two children, with private realms arranged around common space. Courtesy of Loni Gray, All Things Housing ©2017 All rights reserved.

Ultimately, it is not just areas with excess vacant or underused land that are responsible for solving the housing shortage. Established neighborhoods throughout the region can play a critical role by upzoning to allow more housing near transit, allowing for redesign and ADUs and welcoming denser housing back into the neighborhood — for everyone’s sake.