According to a recent update from the California Ocean Protection Council, the rate of sea level rise is accelerating. Future sea level rise at the Golden Gate will most likely range from one to four feet by 2100. If Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets melt faster, ten feet of sea level rise is possible by that time.

Regardless of how high sea levels will be in 2100, or how quickly the rise accelerates in coming decades, in the Bay Area, we will need to re-envision and adapt our complex shoreline to make both our ecological and manmade systems more resilient. As we have written about before, many efforts are underway to assess the Bay Area’s vulnerability to climate change, but so far there hasn’t been a coherent, compelling science-based framework for guiding and evaluating which strategies will be appropriate for our shoreline’s many different settings — from wetlands to recreational attractions to industrial sites.

SPUR is proud to announce the launch of a new project, in partnership with the San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), to fill this gap. The Shoreline Adaptation Strategies project, funded by the SF Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board, will create a new way of looking at the Bay, using science to define different segments or “units” of the shoreline so that we can develop integrated adaptation strategies specific to each one. These strategies could include structural or engineered measures as well as policy and planning tools that address long-term flood risk while protecting people and ecological systems.

The Bay Area is diverse in its topography, how the land is used and who lives and works there, which means different parts of the Bay shore are vulnerable to sea level rise in different ways. To begin to unpack and work with this diversity, our new project begins with defining “operational landscape units” — a concept from landscape ecology — for the Bay shore. These are segments of shoreline that work as a system and have the potential to support ecological systems suited to the given place, along with the physical processes needed to sustain them, such as freshwater flows, tidal range and sediment inputs. Operational landscape units may cross jurisdictions and other traditional decision-making boundaries; they are defined primarily by physical setting and drivers such as watershed boundaries, groundwater basins, wave energy and tidal processes, then refined by consideration of social and cultural boundaries such as land use, population and job density, existing flood protection and infrastructure. Each unit is envisioned — eventually — to have a single coherent adaptation strategy that may include both engineered and policy solutions to increase long-term resilience for that place.

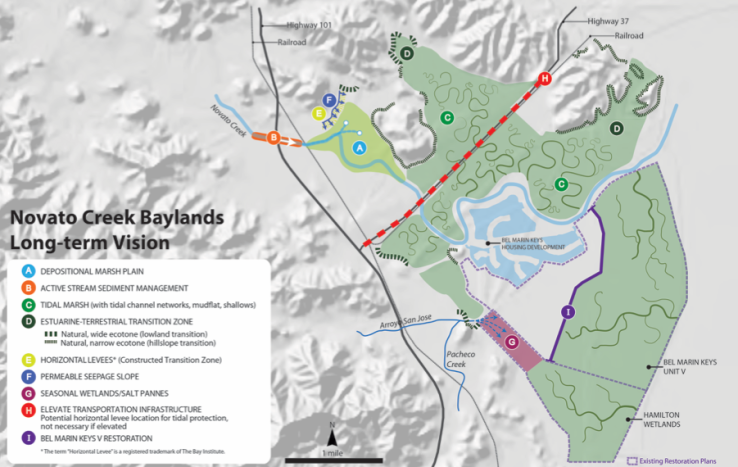

SFEI worked with the concept of operational landscape units to develop a landscape vision for the Novato Creek Baylands in 2015. The project defined a single operational landscape unit based on historical and contemporary geomorphic and ecological conditions and assessed the likely impact of future drivers such as sea level rise, reduction in sediment supply and increased flood intensity. Local stakeholders and regional experts worked together to develop ideas for restoration, including increasing tidal flows, creating a permeable levee that would provide flood protection and freshwater input to the marsh, and a long-term plan for raising Highway 37 to a causeway. This type of multi-stakeholder visioning process could take place within each of the operational landscape units around the Bay once we complete our work to develop “menus” of what is appropriate for each unit.

After identifying operational landscape units, we will identify for each one the potential suite of adaptation strategies best suited to providing resilience for sea level rise. The menu of responses could include hard, structural measures, ecologically restorative measures, and planning tools such as changes to zoning and building codes, establishing easements and transferring development rights, a process by which new development is slowly encouraged to build on ground that is safer than a frequently flooded area.

With the exception of technologies that haven’t been invented yet, this set of measures is largely known already — the innovative piece to this project is the matching of tools to actual landscape units in the Bay Area. Through a collaborative process with a large and diverse technical advisory committee, we will match workable adaptation measures to specific landscape units. We don’t expect this process to result in a one-to-one match of strategies to places, but it will help narrow down the set of workable, durable ideas for any unit from dozens of options to several or just a few.

The result will be a framework for understanding what kind of adaptations could work for real places in the Bay Area to foster a collaborative and data-driven long-term vision for the region. While it is not a planning process or tool itself, the framework — an online resilience atlas and a major report — will be a key resource for future efforts to prepare for whatever sea level rise is coming our way. Stay tuned for updates on the project over the next year and the final product in late 2018.