Over the next decade, more than $10 billion of transportation investments will start to remake San Jose’s Diridon Station into the first high-speed rail station in the country and the busiest transportation hub west of the Mississippi. This historic opportunity has the potential to reshape not just San Jose but the entire Silicon Valley: San Jose recently announced it will negotiate exclusively with Google for up to 8 million square feet of office space.

Throughout the world, projects to (re)develop major multimodal transportation hubs have had transformational impacts on cities and regions. It can happen in San Jose, too — but success is not assured. In the public sector, decision-making about stations and station areas is notoriously fragmented, priorities can conflict and resources are scarce — all of which create obstacles to taking risks or thinking boldly and comprehensively. And yet this type of thinking is critical if Diridon is to live up to its potential.

Major infrastructure and land use decisions will be made at Diridon over the next few months. SPUR proposes seven principles that should guide these planning, land use and transportation decisions. The following are derived from best practices and cautionary tales from international station and city-building efforts, extensive engagement with the public and conversations with technical experts from around the world.

1. Commit to a single, shared vision that is not weighed down by present-day conditions and constraints.

Remaking Diridon Station and the 240-acre area around it isn’t about making room for new rail lines. It’s about fundamentally reshaping San Jose for the better part of a century. To do this, first we need a bold and cohesive vision.

The vision for Diridon Station and the station area should be ambitious, integrated, far-reaching and shared by everyone involved: the city, the public, VTA, high-speed rail and Caltrain. It should lead with a focus on the type of place that Diridon (both the station and station area) will become, with the transit acting as catalytic infrastructure that supports high density land uses and links cities and regions.

In our vision, Diridon becomes a great urban train station and the gateway to the Bay Area. It allows people to be transportation omnivores, because rail, buses, bikes and technology-enabled vehicles act as one intuitive and attractive system that gets them where they need to go — in San Jose and beyond. The station is a public space that connects people seamlessly to the neighborhoods around it and is part of a greater downtown San Jose. New growth is concentrated around the station and is designed to take advantage of unparalleled accessibility, making Diridon a major generator of economic activity. The Diridon we envision shapes and showcases the diversity of the South Bay and is welcoming to all. It is a place where people can walk to meet their daily needs without thinking twice about it, a place where life is lived in public. And this outcome is the direct result of partners who developed a clear and comprehensive vision, leaders who took risks and a governance structure that was set up for success.

It would be a mistake to take today’s conditions or constraints as inevitable. The current land uses and users, financial challenges and fragmented public sector decision-making are not a given. Decision-makers can and should start with a bold vision and work to overcome challenges together. The remaking of Diridon Station and the station area must be viewed as a city-building initiative, not a series of discrete capital projects that happen to be next to each other. This is critical. It will help determine how public and private dollars get spent and will create a goal post to help guide each decision.

2. Create the right governance structure to implement that vision.

Remaking Diridon entails thousands of decisions, including how tall the train platform heights should be, how much developers should pay for public improvements and how high-speed rail should come into the station. They all matter.

To date, each public agency has been making these decisions independently and according to their own priorities, not according to a shared vision. That won’t do.

We believe remaking Diridon Station will not be successful without a consolidated public governance entity that can implement the vision over the long term. This new entity should have some level of decision-making and project-delivery authority over land use, funding and financing, transportation service planning, and construction and maintenance. The new entity should be small, nimble, able to take risks and appropriately empowered to make decisions quickly on behalf of Diridon as a whole — a major asset for the fast-paced nature of construction and project delivery. While the private sector is often a key partner, this is ultimately a public entity responsible for ensuring that the redevelopment efforts contribute to the public interest.

There is also an important role for the state to play in development, leadership and financing in order to achieve success. In France and the Netherlands, local governments apply for a special designation that provides financial resources but also political leadership. Having the state involved is seen as mutually beneficial for the local government and the state. It’s like insurance: both sides honor their promises to make public investments that will have the most positive impact they can.

3. Maximize development capacity near the station.

Although 240 acres sounds big, the land in the station area is finite and valuable. Other cities maximize station areas by building taller buildings. Today, San Jose can’t do that. Located just south of the Mineta San Jose International Airport, the areas closest to the station have a building height limit of about 11 stories due to flight path regulations and airline procedures.

The heights in the station area are limited because aircraft need to clear obstacles (such as mountains and buildings) that are in the flight path even if they lose power to one engine during takeoff. This is a federal rule, but each airline is given a lot of discretion about how to comply with it based on their fleet, technology, flight distance and other factors.

SPUR estimates that buildings could be between 30 and 90 feet taller in some areas, within the current FAA height limits. We conservatively estimate that this could translate to adding 2.3 million more square feet of development capacity in the station area. (For comparison, the new Salesforce Tower in San Francisco is 1.4 million square feet.)

The difference between current airline procedural height limits and the Federal Aviation Administration’s maximum height limits could net an additional 2.3 million square feet of development capacity. The actual amount would have to be determined in collaboration with the airlines and airport. Image by Skidmore Owings and Merrill LLP for SPUR.

The difference between current airline procedural height limits and the Federal Aviation Administration’s maximum height limits could net an additional 2.3 million square feet of development capacity. The actual amount would have to be determined in collaboration with the airlines and airport. Image by Skidmore Owings and Merrill LLP for SPUR.

With the game-changing Google announcement, and at the urging of the San Jose Downtown Association and SPUR, San Jose is exploring opportunities for opening up development capacity while still protecting the health and viability of Silicon Valley’s airport.

San Jose must also minimize the supply of parking at Diridon. Parking is not a good use of the limited and valuable space in the station area. We can either make room for storing cars or make room for people and jobs. Additionally, parking deadens the public realm, making walking unpleasant. To truly embrace urbanism, we should minimize parking, distribute it throughout the greater downtown (making it a “park once” district) and price it appropriately.

Parking also undercuts the billions of dollars that are being invested in transit. People will not choose transit if it is too easy to drive and park. Instead, people should be able to walk to transit or take transit to transit, using more conventional park-and-ride stations (such as the Santa Clara BART station) and light rail as feeders into Diridon.

A two-story temporary parking structure in Kyoto halves the amount of space that parking typically consumes and makes ample space available for bikes. Importantly, this is a temporary structure that can be replaced by new development—offering a phased approach to create a more ambitious land use program. Photo by Laura Tolkoff for SPUR.

A two-story temporary parking structure in Kyoto halves the amount of space that parking typically consumes and makes ample space available for bikes. Importantly, this is a temporary structure that can be replaced by new development—offering a phased approach to create a more ambitious land use program. Photo by Laura Tolkoff for SPUR.

4. Put people first.

Mobility doesn’t stop at the station’s edge. Walking moves the most people with the least amount of space and therefore people who walk should take priority over all other modes of travel. This means shifting from (and deferring) auto-oriented investments like street widening or large amounts of parking to removing physical and psychological barriers to walking and improving pedestrian and bicycle access on all sides of the station.

A rail station can be a link between neighborhoods. Light, transparent building materials and connections, even directly through a station, help make that link at Rotterdam Centraal Station. Photo by Studio van der Valk, Courtesy of West8.

A rail station can be a link between neighborhoods. Light, transparent building materials and connections, even directly through a station, help make that link at Rotterdam Centraal Station. Photo by Studio van der Valk, Courtesy of West8.

Putting people first also means designing buildings and public spaces to create a place that is comfortable, welcoming and engaging. Urban design is not a luxury — it’s essential for making transit successful, creating a walkable neighborhood and building connections between neighborhoods.

The station itself should be designed to connect seamlessly to nearby neighborhoods and be a part of the city’s urban fabric — not a barrier between neighborhoods. This can be done by making the station permeable and accessible from a larger network of well-designed, publicly accessible spaces such as streets, paseos, parks and plazas.

Pancras Square at King’s Cross Station in London is one of many distinctive outdoor spaces that together make up a 26-acre network of public space around the station. Photo copyright 2016 Perkins+Will. Photographer Luca Giaramidaro, All rights reserved.

Pancras Square at King’s Cross Station in London is one of many distinctive outdoor spaces that together make up a 26-acre network of public space around the station. Photo copyright 2016 Perkins+Will. Photographer Luca Giaramidaro, All rights reserved.

5. Prioritize jobs within the station area and add housing, cultural uses and educational uses to support round-the-clock activity.

The transportation investments planned for Diridon Station can dramatically change the city and its economy, but only if the right land use decisions are made. Caltrain, BART and high-speed rail will reach their full potential when the speed, accessibility and reliability of the transit services combines with a strong land use program that gives people many different reasons to come to downtown San Jose.

The density of jobs near transit is the biggest predictor of whether transit is successful, and transit accessibility is one of the top features that companies are looking for. Many international cities have successfully transformed and rebranded their economies based on new access provided by high-speed rail. If a significant amount of new jobs are concentrated in the station area, Diridon can become a major economic engine for San Jose and the South Bay.

But jobs alone are not enough. The Diridon Station area should be active throughout the day and night. Adding housing, cultural uses, public art, recreational uses and public spaces — and programming events and activities there — will support round-the-clock activity and feet on the street.

With Diridon as a major generator of economic activity, it is critical that San Jose open up the ability to build housing in nearby urban villages within walking and biking distance to the station and near light rail.

6. Make transit fast, frequent, all-day and seamless, making it a reliable, attractive and preferred way to get around.

Transit service is the foundation for making the Diridon Station area work. With the advent of ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft, people today have more choices than ever about how to get from point A to point B. These services offer advantages such as extremely short wait times (often less than 5 minutes), door-to-door service, relatively low fares and easy payment from a smartphone. The majority of people will only use transit when it offers better service than it does today.

Imagine if transit to, through and from Diridon were fast, frequent and all-day. Wait times would be shorter. You would never worry about missing “your train” because another one would be right behind it. Trip times would be shorter and more competitive with driving. You could walk up to the platform and go, instead of planning your day around the train schedule. In order for our significant public investments in transit services to pay off, we need to start putting concepts like this into practice. This requires making sure the blended system of high-speed rail and Caltrain offers a predictable timetable and frequent trains at all times of day.

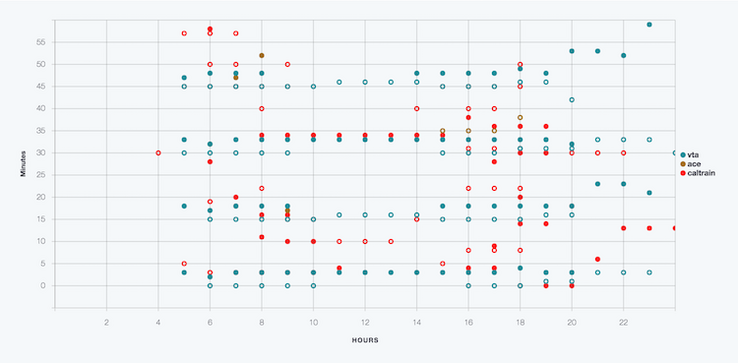

Weekday Transit Frequency in the South Bay

Limited off-peak service makes transit less usable. At Diridon, weekday Caltrain service drops from seven trains per hour between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m. to two trains per hour midday. Light rail service drops from eight trains per hour between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m. to four per hour midday. Graphic by Rahul Gupta

Limited off-peak service makes transit less usable. At Diridon, weekday Caltrain service drops from seven trains per hour between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m. to two trains per hour midday. Light rail service drops from eight trains per hour between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m. to four per hour midday. Graphic by Rahul Gupta

7. Treat Diridon as a “through station,” not a terminal.

Today, Diridon Station operates like a terminal since it’s the southern end-point for many trains, including Caltrain and the Altamont Corridor Express (ACE). This means that many trains lay over or are stored on the tracks, using up valuable track and platform space that could be used for trains that are in motion.

In the future, the tracks and platforms will need to accommodate a larger volume of trains and passengers (up to nearly 140,000 passengers per day). In addition to the arrival of BART and high-speed rail, Caltrain, ACE and Amtrak all have plans to expand service. This means the station and railyards will have to operate like a “through” station where trains stop only for a short period of time for passengers to exit and board. This shift will require some operational changes such as reducing train layover times and changing the signal system. But it may also include some bigger capital investments, such as rebuilding platforms so that both high-speed rail and Caltrain can use them, building passing tracks, fully depressing light rail underground at Diridon, and possibly turning a different Caltrain station into a southern terminus.

Next Steps

To deliver a place worthy of this once-in-a century opportunity will require bold leadership, visionary thinking, and new ways of working. Fortunately, there are models around the world that we can look to as we move forward. SPUR has launched a multi-year initiative to help shape this monumental transformation. Stay tuned for our upcoming SPUR report, lunchtime forums and more coverage on our blog as our research progresses.

Many thanks to our contributors Eric Eidlin, a fellow with the German Marshall Fund of the United States and Luca Giaramidaro, an urban designer with Perkins + Will. Together they planned Rail~Volution’s California Day, with a special focus on Diridon, and have provided a wealth of information about station and city-building efforts around the world.

Thank you to Ellen Lou, principal, and Kenichiro Suzuki, associate, at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill for providing technical assistance to explore building height restrictions in the Diridon Station area.